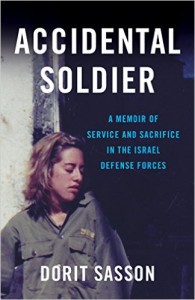

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share with you the first chapter from Pittsburgher Dorit Sasson’s Accidental Soldier: A Memoir of Service and Sacrifice in the Israel Defense Forces.

Accidental Soldier is Sasson’s story of “how she dropped out of college and volunteered for the Israel Defense Forces in an effort to change her life―and how, in stepping out of her comfort zone and into a war zone, she discovered courage and faith she didn’t know she was capable of.”

Accidental Soldier publishes this June 14, 2016 and is currently available for pre-order.

I am waiting at the Koach junction to hitchhike back to the kibbutz, mesmerized by the peach-colored Mount Hermon in the far distance, when an Israel Defense Force soldier—clad in white, which means he’s part of the Air Force—slams the door of the vehicle he’s just gotten out of. I’ve watched these soldiers hitchhike for the past three weeks, ever since I got here. This particular one makes his way past the yellow line of the trampiada—a curved cement stop made especially for soldiers—and approaches me. To my right, another mountain looms before me, its features in better focus: I can make out the red kalaniyot flowers native only to Israel, interspersed with other wildflowers, dotting its surface.

I am waiting at the Koach junction to hitchhike back to the kibbutz, mesmerized by the peach-colored Mount Hermon in the far distance, when an Israel Defense Force soldier—clad in white, which means he’s part of the Air Force—slams the door of the vehicle he’s just gotten out of. I’ve watched these soldiers hitchhike for the past three weeks, ever since I got here. This particular one makes his way past the yellow line of the trampiada—a curved cement stop made especially for soldiers—and approaches me. To my right, another mountain looms before me, its features in better focus: I can make out the red kalaniyot flowers native only to Israel, interspersed with other wildflowers, dotting its surface.

The countryside here is pristine. There are still quite a few hours left in the day, but already a cool breeze runs through my T-shirt. It gets cold in this part of the woods, which tells me that by the time I reach the kibbutz, I’ll probably need a sweatshirt.

“Do you know when the bus is coming?” the soldier asks in Hebrew.

“I think the buses are all finished for the day,” I say politely, also in Hebrew.

“I guess that means we have no choice but to hitchhike, right?” he says. He seems a bit jittery, but there’s a huge grin plastered on his face.

I’m startled by such a question. Soldiers get rides from civilians all the time here, because the Israel Defense Forces are the lifeline of the nation. They serve to protect the country. So his chances of getting a tramp, or hitchhike, are high. But I’m just a kibbutz volunteer—this is my third trip to Israel and my first hitchhiking experience. I’m not so sure anyone will pick me up.

It’s five in the afternoon and the buses to this area of the Galilee are all finished for the day, but if I can’t find someone to give me a ride, I can always call my aunt and uncle; they live at Kibbutz Malkiyah, tucked back in the Galilean Mountains.

Perhaps this soldier senses the “Israeli” part of me because of my Mediterranean features—the hazel eyes and dark brown hair I inherited from my Israeli father. Plus, I’m not sitting with the rest of the volunteers, who are all Swedish and Danish and are camped right on the main road, yapping in their native tongues. At this point, I slip in and out of Hebrew and English just like I would with a pair of well-worn sweats. I’m tickled by this moment, and can’t help but wonder why the heck an IDF soldier would ask me about the bus schedule, since they aren’t really dependent on them. No IDF soldier has ever even approached me before.

I have zero experience hitchhiking in the States, and even though it’s my first time, I feel comfortable doing it here. Perhaps it’s because, like most Americans my age, I’ve been influenced by Hollywood movies and my image of soldiers is glamorized. Maybe it’s because there’s a certain camaraderie of trust and solidarity here in Israel—the understanding I have here that I’m being protected all the time. Whatever the reason, I don’t hesitate to stand out in the middle of the road and stick out my index finger with my elbow comfortably resting on my side, just as I’ve observed others doing in the few short weeks since I arrived here.

Just then, a car approaches, and the driver signals that they’re about to stop.

Hey, I did it, I think. My first hitchhike!

But instead of stopping alongside me, it stops farther up the road. The soldier turns around, sees it has stopped, and runs towards it. He talks to the driver through the passenger-side window while carefully holding his M16. Within a few minutes he’s back and the civilian vehicle is off.

He runs back still holding his M16.

“It’s not going where you need to go?” I ask.

“No, they’re going to a different place.”

“Oh.” I notice he doesn’t use the words “camp” or “army base,” making this IDF world still a bit mysterious and a bit secretive.

I’m eager to use my university Hebrew. If Mom were here, she’d grab my shoulders and whisper fiercely, “Watch out, they’ve got guns. Don’t get too close.” But their guns don’t shake me up; here, I can take a step closer, eavesdrop a bit.

The soldier steps out onto the road again with his index finger out, moving his boot in heel-toe-heel-toe fashion. Bustling bright. Olive skin. Dark hair. Curly. Just like my Israeli father.

It’s the summer of 1989. I’m eighteen years old. Just a few months ago, my father, Israeli-born and raised, offered me money to travel around the world. It was my last chance to explore my options: Would I postpone another year at SUNY Albany, or travel? As a freshman, I was unhappy and aimless. Dad complicated my life by holding up a picture of a twenty-two-year-old named Tania Aebi who’d made headlines in The New York Times by traveling around the world in a small boat. The newspaper clipping showed her entering New York harbor with a big wave and wide smile. I wanted to be that free. No obligations to school. I read the last words of the article over and over again: She intends to write a memoir of her travels one day.

“You see? This is what it means to travel the world,” Dad said, grinning and pointing to the boat with an I-told-you-so sort of look.

The idea of traveling around the world worried me, though: Would I have enough money, even with Dad’s help? What if I didn’t want to go back to school after that? How would I manage so long on my own? Where would I possibly go, and who would I go with? Nobody I knew was traveling around the world. Still, the idea of stepping outside my comfort zone was appealing. So I decided to start small, and to focus on the one country I knew something about: Israel.

I seized the idea of volunteering on my aunt’s kibbutz way before I really knew what a kibbutz was. Volunteering, I reasoned, would be an inexpensive way to visit the country. She and I corresponded in the fall of 1988 via airmail. I yelped when I received a red and blue envelope with Hebrew writing on it and with the word ISRAEL spelled out in English on the front.

“No problem,” she’d written in response to my initial letter. “I spoke to the person in charge of volunteers. We have a place on Kibbutz Malkiyah for you.”

What a perfect deal. I could still travel in Israel, I’d be with Dad’s family, and since I’d be working and Dad was paying for the flight, I wouldn’t need to shell out much money. I had finally found a way to break free from the two opposing forces of my life: my dad and my mom.

Mom was a child prodigy and a Julliard graduate, and today she is a classical pianist scared of anything that’s unfamiliar, including Israel. She and her family escaped the Nazis in the mid-1930s, when she was an infant, leaving her home country of Spain for Panama. Eventually they left for the US, where she settled in New York. She concertizes around the world, and Israel is the one country that triggers fear and insecurity in her; unfortunately, I’ve inherited quite a bit of her fear.

She’s always told me I have to “be somebody,” and that starts with getting a college education. But starting when I was eleven, she left me in charge of taking care of my brother so she could practice with legendary masters on the Upper West Side. And she always came back late—too late. She’s a New Yorker through and through, and so despite the prevalent crime and unsafe streets of the ’70s and ’80s, she always took either the bus or subway home.

After one late night practicing for an upcoming gig with Leonard Bernstein at Carnegie Hall, Mom told me I should consider becoming a teacher. “It’s the one thing you can fall back on,” she said. Aside from teaching Holocaust survivors a music survey course I designed at a vacation center somewhere in Pennsylvania a year or two ago, I have very little teaching experience, but the idea of pursuing a stable profession is appealing. She and my dad are both artists, so I know what it’s like on the other side. She doesn’t want to see me struggle, and I don’t want that either. Plus, it’s hard to follow your passion when all the freshmen in your graduating class are declaring pre-med and law majors. But I want to do the “right” thing, and I still don’t know that “right” thing is. It’s frustrating.

Then there’s Dad, a Fulbright graduate and visual artist who sees the world through oils and canvas. Between my two parents, he’s the more logical and subtle one. So I’m following his philosophy of exploring my options without ruling college out—except that I’m staying with my Israeli family rather than actually traveling around the world, which makes me feel like I’m taking a shortcut.

He says to me in earnest, “I’ll give you the money. Just take it and go!”

“I don’t want to!” I’m defiant—a practice I’ve learned well from years of maneuvering between Dad and Mom, especially since Dad testified in court that Mom wasn’t fit to be a primary caregiver and then moved out. I was twelve at the time.

“You’ll regret it,” he says. “Believe me.”

“Nope, I don’t think so,” I say smugly. Years later, I will regret that I didn’t take him up on his offer. How much does Mom’s fear and anxiety control me? Dad is fully aware of her controlling tendencies, but he has no idea how much they influence my decisions.

By the time this volunteer stint rolled around, I had finally managed to tap into that “higher-up” that I today call my “Jedi” voice and had conquered my fears. If Tania can do it, so can I, I reassured myself. It’s Israel—a country I’ve visited before, the homeland of my family. I’ll be staying with my aunt and uncle. I’m somewhat familiar with kibbutz life.

Dad didn’t say much when I said, “I’m going to volunteer on Malkiyah.” This time there was no defiance in my voice and Dad wasn’t trying to fight my decision. But we both knew that going to Israel was a deviation from the grander scheme of things. Perhaps I’d placated him in some way with the fact that I was going to volunteer in his homeland, but I’m sure at least a part of him was disappointed by my choice.

By the time my round-trip ticket was bought and my bags were packed, I was less jittery. The dots of earlier memories were starting to connect. I began vaguely to recall my aunt and uncle’s kibbutz from two previous family visits—the first at age three and the second at twelve. I remembered that it took at least twenty minutes to get to, driving along a very circuitous, narrow road. In the car, sandwiched between two grownups, the twelve-year-old in me paid special attention to the darkness on both sides of the car.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“On the way to Malkiyah,” someone said.

A barbed wire fence came into view under dim lights. “And what’s that over there?” I asked, pointing.

“Lebanon,” my aunt said. I almost could taste the Leben, a thin, unsweetened yogurt that Mom often bought and thickened with jam so it would appeal to my American taste buds. Leben, Lebanon—similar sounds. I remembered how I turned up my nose when I discovered the Leben wasn’t sugary and processed like the other yogurts at the grocery store. This time, though, I was ready to taste other experiences.

I look at my watch. It’s just this soldier and me hitchhiking farther up the road for almost an hour. The Swedish and Danish volunteers just a few meters away don’t really seem to care how they’ll end up getting back to the kibbutz, and they’re still jabbering away.

Just when I’m about to pull a token to make a call to my aunt, an army Jeep turns onto the road—its headlights blinding—and after passing us, it stops, right where the curvy road takes a sudden turn and disappears around a bend. Technically, soldiers can only pick up other soldiers or reservists, which explains why it stops so far away.

I get up from the curb to approach the Jeep, the first vehicle to arrive within the last hour. There are a limited numbers of seats available in the car, and by the time I get close it’s clear that I’ll be beat out by the soldiers, a few of whom are already swarming the driver’s side window. I have no chance of being picked up. But still, I take a few steps closer, near enough so I can peek into this foreign world.

They’re packed in like sardines—all of them with war-painted faces. They are on their way to Lebanon, but they will stop first at one of the neighboring bases up the hill to drop off a few soldiers. I know this because I overhear them chatting in Hebrew. The six soldiers in the back wear green helmets, and one of them shouts something to the Air Force soldier, who runs to the Jeep, opens the door, and then runs back to grab his green duffle bag.

Then the Jeep moves in reverse and stops where I’m standing, still with my index finger raised.

“Where do you want to go?” one of them asks me.

I lower my finger. Seriously? Will they take me? A volunteer?

“Kibbutz Malkiyah.” I immediately feel self-conscious about my accent. I worry that I sound like a cow chewing its cud, and yet I’ve never felt the confidence I do right now.

“At Americayit?” he asks. Are you an American?

“Ken.” Yes.

“Me-efo?” From where?

“New York City.”

“Ah—New York City,” the soldier says in a charming accent, as if I’ve just mentioned the land of his dreams.

New York City. Each time I tell Israelis in Israel where I’m from, their eyes light up like I’ve just handed them the jewel of the Nile. They are always asking me, “Hey, do you know so and so from Queens?” I didn’t understand why in the past, but on this visit I have finally realized that there are many Israelis living in New York City, and the Israelis here think that my corner of the world is like a mini-Israel. I used to think they thought America was a country paved with gold, but now I understand: it’s not the riches they’re driving at but the need to connect.

I take one step closer to the Jeep, aware of the boundaries between us. I’m a volunteer. There are male soldiers. But I’m not your typical volunteer. First, I’m Jewish; second, I’ve got an Israeli father; and third, I speak better-than-average Hebrew.

There are sizeable backpacks in the back of the Jeep. Because I backpack everywhere, I can easily see myself squeezing in like another sardine and chatting with the seven soldiers occupying the space. I welcome the physical closeness that my American peers might find off-putting. I find the diversity of their appearances appealing as well. Although dressed uniformly, their facial expressions, hairstyles, and even the way their paint is smeared are all different. One has what appears to be bangs under his helmet, while another has long, stringy hair. One has green eyes and another has brown. (I’ll fit in with my hazel eyes and long brown ponytail.)

As the Jeep starts to move, I step closer. Now I’m just a few inches away from the door. One of the soldiers leans out the window and shouts something incoherent in Hebrew. He smiles sheepishly. Pretty soon all seven male soldiers turn to look at me. This little interaction has gathered some attention. Even the volunteers who are sitting a few yards away are now closing in on me, and all I’ve really said is “Kibbutz Malkiyah.”

Air Force soldier leans out of the window and says something, then looks at me closely. For a moment I think he’s speaking to me, but then I realize he’s carrying on a conversation with his soldier buddies.

“Hey, Shalom, there’s not enough room in our Jeep to take her?”

“Shimon, are you crazy?”

I know it’s illegal to bring a civilian on board, but I figure it’s illegal like not buckling a seatbelt—a soft law. I can feel them sizing me up. I’m not one of those drop-dead gorgeous Swedish volunteers IDF soldiers are known to gravitate toward, and as this thought crosses my mind my confidence suddenly deserts me and I feel terribly self-conscious.

One of the soldiers continues to look at me as the Jeep begins to pull out. This is the closest I’ve ever been to an IDF soldier. On the kibbutz I see them eating lunch in the dining room after their shifts, but that’s about the extent of my exposure to them. I’m in awe of them, and being so close now prompts all sorts of questions: Who are they? Do they go into Lebanon and blast their M16s? Do they blow up houses? How do they attack? I feel so sheltered, and it seems to me that what a soldier goes through is the “real” world.

From a young age, Mom pulled me away from the news every time Israel was announced on the media. Sometimes she would cover my eyes; other times she physically pulled me away from the television and turned it off. It was clear she hated Israel and was deeply afraid of the terrorists who so desperately wanted to blow it up.

Dad, on the other hand, was hungry to connect with his homeland. News was the only way in. He’d watch with intent as Golda Meir, Israel’s first and only female prime minister, bellowed about her big visions for social and political reform for the country while my father steadily commented in a tongue I couldn’t yet understand. Years later, I was given a picture of my father, a young Fulbright student, shaking hands with the famous Golda, and I began to understand. She wasn’t just this political person on TV. She was someone my father had actually met.

The soldier could be looking at anything—my pea-sized breasts, my lanky arms, or maybe even the ponytail I’m afraid to release from its everlasting bun. I hear the chorus of a song I’ve grown to love—“The Weakness in Me,” by British singer Joan Armatrading—coming from the speakers in the Jeep. Israelis and volunteers love to sing this song while swaying huge cans of beer and knocking heads at our local kibbutz pub.

My mom’s fears and worries about Israel make this experience that much more thrilling. Later, when I’m back in New York, I’ll start thinking of ways to make up for missed time—to get to know these people that I’ve always been told are “war monsters.” For me, Israelis are far friendlier than Americans. And maybe I’m just naive because I’m just a tourist, but I feel more comfortable, and safer, here than I do in the US. I love how, when we return from our various volunteer trips, the IDF soldiers we pass at the entrance to the kibbutz always raise their hands in a sort of salute before opening the gate for us.

I watch the Air Force soldier squeeze in with the rest of the soldiers and get swallowed up by the sea of uniform green inside. After they talk among themselves for a moment longer, the Jeep moves on, leaving me feeling a jumble of emotions. I just talked with IDF soldiers! My hands are shaking. I also wonder if I’ll ever get home.

I turn back to the road and stick out my index finger again. I’m hitchhiking in paradise, but now that my soldier friend is gone, I feel alone. In front of me is the majestic Hula Valley, resplendent with fish ponds, and Mount Hermon in the far-away distance. If I were to walk a kilometer up the mountain I would be able to see what this prized area, one of the prettiest in the country, is known for: squares of green and brown patches of farmland.

In a matter of moments, a big white van stops for me, and luckily there’s room enough for all five of us. But when I climb in, I discover right away that there are no seatbelts. The Danish and Swedish volunteers immediately prop their knees against the seats in front of them, unworried. Why aren’t they scared? I think, panicking. How can I ride in a car without seatbelts? I take a deep breath and remind myself not to act like my mother.

As we ascend the mountain, we pass apple orchards and fish ponds. Under the early evening sun, the ponds shimmer like diamonds. Soon enough, dense forests, rigidly bunched, take over both sides of the highway, and for a while there’s nothing more to see. On a clear day, there’s a bird’s-eye view all the way to Kiriyat Shmona, the next farthest town, and even to Metulla, known as the last stop moshava before hitting Lebanon. But now there’s only blackness between me and the rest of this unknown part of Israel—the same blackness I remember from my last trip up this mountain at age twelve.

I find myself leaning out the window, looking for the fish pond in the cozy, carpeted blackness of the night. The Israeli driver makes small talk in broken English, but I’m too nervous to engage. I’ve never hitchhiked in my life, and as much as I’m trying to ignore the seatbelt problem, it’s difficult for me to relax. I grab on to what appears to be a holder above the side window, just like Mom used to do when I was growing up any time she was in the car with Dad. A scene from my childhood comes to mind:

“Drive slower! Can’t you drive a bit slower?” Mom shouted loudly over the rickety grating sound our four-door burgundy hatchback made as we crossed the Brooklyn Bridge. She grabbed the holder next to her with two hands. My seatbelt had become unbuckled, but no one noticed. I paid attention to the noises: one long grate and then a thump . . . buh-ump!

“Ahron, PLEASE SLOW DOWN!”

But Dad didn’t, and Mom continued to shout.

We reached the end of the bridge, and he finally slowed down.

“Okay, Mimi,” he said.

Ignoring him, Mom turned to me and said, “What happened to your seatbelt?” She reached over to fasten it. When it suddenly came apart again minutes later, I didn’t bother closing it again.

Now our driver snakes up the mountain and finally onto a straight road offering a multitude of directions. Signs in misspelled English point to various kibbutzim and army bases. Our driver turns right and left and left and right. Each turn brings us closer to Malkiyah, which sits on flat land just a few meters from the Israeli–Lebanese border. I know this because for the last week I’ve passed by this particular Galilean mountain—one of the higher ranges here. As we curve around the hill, I spy what appears to be a little hut, and a kibbutz member tells me it’s an abandoned watchguard tower left over from the 1967 Six-Day War, and not used anymore. It’s the same kind of tower I’ve seen on the other side of the barbed wire fence where my aunt lives, past a lovely expanse of quiet ridged rock and wildflowers that could easily be mistaken for Central Park.

By the time we enter the kibbutz gate, I’ve opened the window so far and wide that the cold air from the mountains is wrestling with my long brown hair. I fish several strands from my eyeglasses and hold them in one hand to keep them from spinning around me.

Could the Israel Defense Forces really be an option for me? I can’t get those IDF soldiers out of my mind. A seed has been planted. This could be my calling.

The van parks outside the dining room, and we walk up a little hill that brings us to a row of one-room volunteer quarters. The cold water I wash up with feels good against my sun-exposed skin. After a full meal of Israeli-style salad and hard-boiled eggs, I continue to entertain the thought of changing the course of my life. I know I won’t be able to stay on this kibbutz forever; in fact, I’ve got only four weeks left until I go back to the States.

From the US, I could see myself as a volunteer on a kibbutz but never as a soldier. But now that I’ve seen how integral soldiers are to the nation, I’m struck by the fact that young men and women are “born” into service from day one. I’ve never served or volunteered for anything before this, and even though I have been an Israeli citizen from birth thanks to my father, it was always clear that there was no expectation of my serving in the Israel Defense Forces. Even ignoring her aversion to Israel, Mom always thought volunteering was a crazy waste of one’s time. But now I wonder: Who are these people? What motivates them to serve their country? Will I ever be one of them?

After dinner, I try falling asleep next to snoring roommates, and instead lie there agonizing over these questions, afraid of what the coming years will bring. I’ve got this tendency to stick my hand way out into the future instead of just enjoying the moment. For years, friends have told me to stop thinking so far ahead—to be in the here and now.

“Just look at the step in front of you,” a wise old friend would say. “Don’t look too far ahead. One baby step at a time.”

Now, as the pine trees rattle and shake relentlessly outside our window, my own voice says, Stop agonizing over the questions. Just enjoy the experience. You’re only in Israel for a short time.

But I counter myself sharply, I still have to make a decision. I don’t want to be unhappy again for another year at college. No way.

I find myself quoting poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s words to myself. I’ve memorized them by heart with the help of a note I’ve kept tacked on my wall all these years:

Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms…

If I were in my New York City loft room, I would simply have acknowledged these words for their beauty. But here, facing the unknown of my future, the words “live the questions” and “do not seek the answers” hold profound personal meaning. I’ve always thrived on having the answer; I’ve wanted to do everything right, and to do it in one straight, organized line. To do what’s expected. Now that I’ve deviated from that, I’m on my own. I have a decision to make, and, knowing myself as I do, it’s not going to be easy.

This excerpt from Accidental Soldier is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.