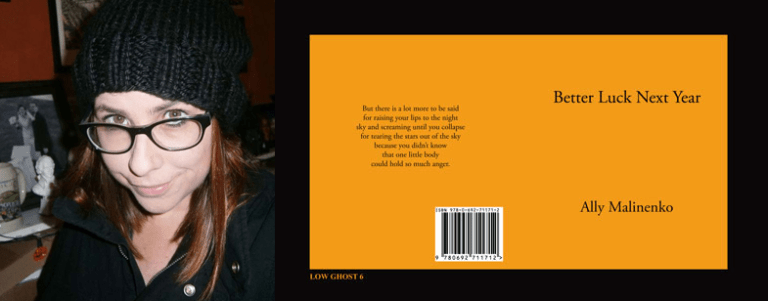

Ally Malinenko is the author of the poetry collections The Wanting Bone and How To Be An American (from Pittsburgh’s Six Gallery Press) as well as the novel This Is Sarah (Bookfish Books). She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, but will be visiting East End Book Exchange on July 23rd to celebrate the launch of her most recent poetry collection, Better Luck Next Year.

We asked Malinenko what she hopes readers take away from her most recent collection, which Low Ghost Press has very kindly allowed us to excerpt below!

Ally Malinenko: “I think the reason anyone writes anything, or reads anything for that matter, is to connect with another person. To put something into the universe that a stranger picks up and says, ‘Yes, I know that! That’s me!’ To cultivate empathy – something we could all use a little more of. Cancer is an incredibly universal disease. You can’t throw a rock without hitting someone who has been affected. But it is also exceedingly isolating. There is a clear demarcation between the life you used to have and the life after diagnosis and it bleeds into nearly every aspect of your existence. So what I tried to do is speak to that as honestly as I could. It was an attempt to dismantle the ‘warrior myth’ and fetizishing of breast cancer. When you scrape away all the ribbons and charity walks you’re left with some very harsh realities. So if there’s anything I hope that people get out of it it would be the ability to speak more honestly about our shared fears and hopes. To speak as honestly as we can about mortality – our own and that of those we love.”

The Waiting #1

When it is Monday

I am both too close

and not close

enough to Wednesday

which is the day

I should get the call

about the biopsy.

And I am not doing well

one drink away from tears

or stupidity

and you are trying

telling me it’s fine

and I am nodding

wanting to grab you

and shake you and

scream

It’s fucking cancer.

I know it.

I saw the doctor’s face

when she turned

to wash my blood off her gloved fingers

after dropping bits of me

into a jar for the lab

and I said

Hey Doc, you’re not worried are you?

craning my neck

to see her face

from this operating table

and she said

Yes, Allyson

using my full

name the way people

who don’t know me do

she said, Yes, Allyson, I’m very worried

before yanking off her gloves

dropping them in the sink

and walking out the door.

The Taken

Do you have kids?

the resident doctor asks.

I look at his nametag but he turns too quickly for me to catch it.

No, my husband answers for me.

The resident frowns. Okay, he says.

Do you want to have kids?

No, I say, casually. No.

I say it again trying to sound resolute.

Oh good, he says with a big sigh of relief

and a wide loose smile.

That will make my job way easier.

Cause that’s off the table once we start treatment

and now we don’t have to worry about saving eggs.

He mimics wiping sweat from his brow and

moves on to the next question.

In my head I picture a chicken roost.

And right there

everything comes together.

Needle sharp.

I see the split in the road.

And it is permanent.

There is a hard cold difference

between setting down something precious

and having it pulled from your hands

still wet with afterbirth.

The difference between

Don’t Want and Can’t Have.

And just like that

I have changed camps.

Better Luck Next Year

I’m not even sure why I kept it so long

this pewter pink ribbon pin

that was given to me during radiation treatment

that first day when the nurse walked up and said

I have something for your collection

nodding at all the pins on my bag

and placed in my hand a little pink ribbon

a symbol

a mark

and I took it with quivering fingertips

there in my hospital gown

waiting to be burned

because I didn’t know what else to do.

I put it on my bag with the others

and there it stayed

through all of treatment

through the tears

and the panic

the sick dizzy feeling

in the middle of the night when I got up to pee

the one that told me

You’re going to die. Sooner. Painfully.

It stayed there through the injections

and the long hours spent in the waiting room.

It stayed there through telling my parents

and my friends and the depression

and the anger that crashed against me like a tidal wave.

It stayed there until

yesterday

when I looked down at it

and realized

I don’t want a symbol

and I don’t want to be a warrior.

I thought of all the young women that came before me

the ones that died

and the ones that lived

and all the others

out there right now blossoming

this burden in their holy bodies.

I thought of all the things people told me

when I told them about this hurricane of a tumor in me

and it was yours that came back to me:

Better luck next year, I guess.

You said it not insincerely

but with the exacting honesty

of the unchangeable

unfairness of this life

and I took the ribbon pin off my bag

because I am not a warrior

or a survivor

but just a young woman trying to live with a disease

and I hurled it over the

wrought iron of the cemetery fence

and I kept walking

not caring to see which grave it landed at

knowing that at least

it wasn’t mine.

Better Luck Next Year is excerpted here by permission of Low Ghost Press.