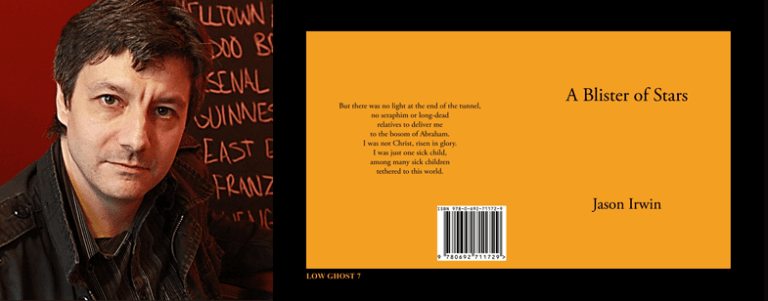

Jason Irwin is the author of Watering the Dead (Pavement Saw Press, 2008) and the chapbooks Where You Are (Night Ballet Press, 2014) and Some Days It’s A Love Story (Slipstream Press, 2005). He has also had work published in Poetry East, Sycamore Review, Confrontation, and Poetry Ireland Review, among others, and is a Transcontinental Poetry Award-winner. Irwin grew up in Dunkirk, NY, and now lives in Pittsburgh, where he’ll be celebrating the launch of his most recent poetry collection (A Blister of Stars, Low Ghost Press) at East End Book Exchange on July 23rd.

We asked Irwin what he hopes readers take away from this most recent collection, which Low Ghost Press has very kindly allowed us to excerpt below!

Jason Irwin: “I hope the reader takes a way a feeling, or idea of survival, as well as the idea that the everyday, ordinary events in peoples’ lives are actually extraordinary; that there is beauty amid all the dung.”

Ouija Board

My cousin asked the usual questions –

boys and marriage; were there any more toys

under the Christmas tree?

I asked When? And How?

I was thirteen. My cousin, twelve.

It said I would be forty-one.

The same age my mother was that Christmas.

Elvis was forty-two when he died. Jesus, thirty-three.

After that I waited, counting down the days

and weeks. The years.

Whenever we played war

I was always the soldier who got killed, the one who died

a heroic death. Sometimes

I lay on the couch with a towel over my face

and instructed my cousin to pretend it was my funeral.

It would be on a Tuesday.

Would it hurt? Would there be blood?

The night before that fated day I dream

I’m standing before the Oracle at Delphi;

that my cousin and I are trapped on a frozen lake

When the ice begins to crack, my cousin slides away

from me, trying to collect the walnuts that spill out

of the bag she is carrying.

“Don’t be obstinate!” she calls to the nuts

that lie there playing dead, looking like turds.

In the morning I watch the sun pass through the clouds.

After my third cup of coffee I pour another

and move to a chair near the window.

Outside a boy is standing in the street jumping up and down

on each crack in the pavement, fearless.

Monster

I was a zygote then,

a coin in my mother’s purse;

a fish swimming in the brine

of her sins. I was the tiny monster

growing inside her, always needing,

always reaching.

Then, swaddled in my disfigured armor,

I howled and squirmed. Priests

and soothsayers were summoned

with their incantations and blessings.

But the monster lived, consumed our lives,

and became something other –

a manifestation of our fears.

On rainy nights when the roof leaked,

when the bills piled up, nights I lay in the hospital

waiting for X-rays or surgery,

the monster’s shadow stained the walls.

Sometimes I imagined he was a warden locking the doors.

Sometimes he was the doctors, with their tiny knives

and mouse-black eyes. Sometimes I swear he was God.

Tethered

I

December, a few weeks before Christmas,

and I’m in the hospital again.

Another round of doctors, nurses,

and interns with ballpoint pens and endless

questions. X-rays and scans; stiff sheets,

piss bottles, and little plastic cups

of ginger ale. Another week

out of school; another surgery.

But this time is different:

my club foot will be amputated.

The doctors assure me

I will be better off in the long run.

Yet I am sick and tired of hospitals,

of surgery, of checking my blood

pressure and temperature,

the beeping of IV machines.

Outside snowflakes fall like a million

Eucharists, and on the far wall Jesus hangs

on his cross like a kite. I lie awake

tracing the scars that crisscross my body

as shadows flood the room.

I imagine my blood draining, spilling out

in majestic rivulets of crimson.

II

In the morning they lay me on a table

and wheel me to a room cold

as chrome, where giant parrots,

dressed as doctors, perch –

their green wings shining

like knife blades

in the halogen radiance.

I die that day – vancomycin,

cardiac arrest – but wake

as if only seconds have passed,

my club foot still attached.

Everyone is gathered around

as if in vigil, eager for news

about that place their faith

assures them I have traveled to.

But there was no light at the end of the tunnel,

no seraphim or long-dead

relatives to deliver me

to the bosom of Abraham.

I was not Christ, risen in glory.

I was just one sick child,

among many sick children

tethered to this world.

A Blister of Stars is excerpted here by permission of Low Ghost Press.