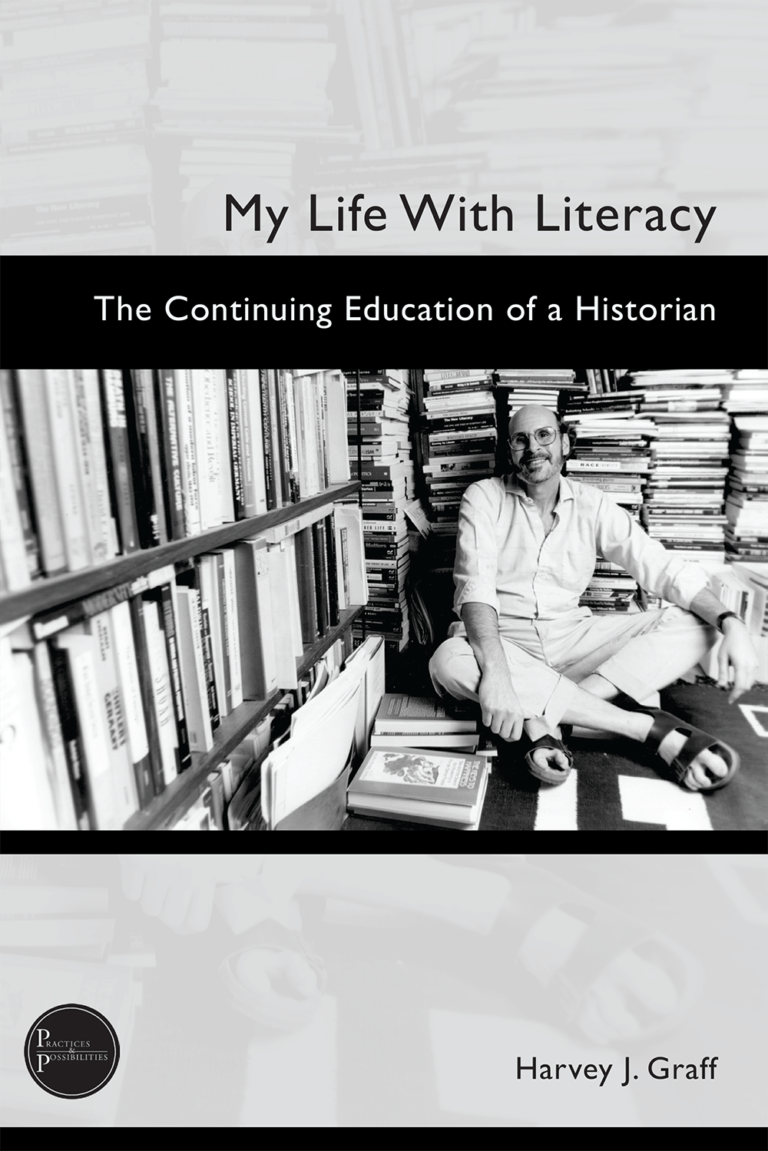

From the Publisher: “Calling My Life With Literacy a ‘new intersectionality,’ Harvey J. Graff explores both overarching and underlying patterns that connected his development and lived experience from birth and childhood in Pittsburgh primarily in Squirrel Hill to age 18, and through his retirement from the academy. He considers the inextricable interconnections of personal experiences and relationships; the political, broadly defined to include life-shaping contexts and historical events, influences, values, commitments, and experiences; the social, intellectual, and political dimensions of academics and scholarship–a life of learning and using literacy and literacies; and the circumstances of living in six major cities and studying and then teaching in five universities.

Graff’s pioneering scholarship in the history of literacy and literacy studies provides both the frame and the foundation for his work in the history of children and youth; the history of cities; higher education past, present, and future; and interdisciplinarity itself.

The Open Access edition of the book is at https://wac.colostate.edu/

books/practice/graff/. This book will be available in a print edition from University Press of Colorado in the coming months.” More info About the Author: “The child of a mother born in Sharpsburg (family hardware business) and a father in Braddock (jewelry store), Harvey was shaped significantly by the environment of a dominant Steel City and baseball and football power (he attended one game at Forbes Field during the 1960 World Series), through the late 1950s and 1960s collapse of Big Steel and the incomplete transition to a New White Collar and High Tech Hub symbolized by the Golden Triangle surrounding The Point. His memories include the incline to the top of Mt. Washington and the Bridge to Nowhere.

From a first year in Greensburg, family matters took him to Highland Park, then Beechwood Gardens, Northumberland St. near Linden Elementary School, and Monitor St. near Taylor Allderdice. He and his cohort were part of the clinical trials for both the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines developed at the University of Pittsburgh Medical School.

During his childhood and adolescence, the area was strong, growing, and safe predominantly middle-class and Jewish inner-city area. The public schools were excellent. Allderdice competed annually with a Philadelphia private academy for the most National Merit Semi-finalists in the state. At the same time, Allderdice only won in swimming and tennis.

His classes were bussed to Conductor William Steinberg’s Pittsburgh Symphony’s splendid children’s concerts. On one occasion, a small group appeared on an early telecast of Mr. Rogers on WQED before network TV and Public TV. His memories are stirred when visiting Rogers’ room in the Heinz History Center.

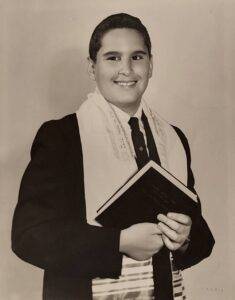

The child of children of immigrants from Eastern Europe, Harvey was Bar Mitzvah’ed at the Tree of Life Synagogue in the chapel of the original building. His 11-year younger brother’s ceremony was in the recently destroyed newer structure.

While wealthier classmates and private school cohorts played at country clubs, Harvey played golf at Schenley Park until age 13 when he shifted to tennis, especially on the courts at Mellon Park and the clay at Frick Park. He swam and attempted to box at the YM&WHAs first in Oakland across from the Cathedral of Learning and later at Forbes and Murray Avenues.

Family haunts ranged from Weinsteins to Mineos and the Murray Avenue bakeries and delis. Or a drive for Station Street Hot Dogs. More relaxed dinners led to Poli’s and special occasions to Park Schenley.

Adolescence in the mid-1960s is discussed at length in Chapter 3.

Historian Harvey is certain that he grew up during both Pittsburgh’s and Squirrel Hill’s finest hours. The contradictions of his era included working summers in the declining steel mills across the river in Homestead to earn money for college costs. He got the jobs, not surprisingly, though family connections. And the cultural and educational endowments of Robber Barons Carnegie, Mellon, Frick, and others.

From Allderdice, his educational paths went first to Northwestern University for a BA with honors in History, and then to the University of Toronto where he earned his MA and PhD in the then “new social history” studying with some of the best scholars of their generation.

From Toronto, he and wife Vicki moved to Dallas as they confronted one of the worst academic job markets in history. The complicated path elaborated in the book ended at Ohio State University as the first Ohio Eminent Scholar in Literacy Studies and Professor of English and History.

The Graff are now returning to Chicago, their own “second city,” having met at Northwestern in 1969 and lived there in 1973 and 1979-1981. A condominium in an 1894 building in Lincoln Park is their next stop.

On visits to Pittsburgh, they take in the renovated dinosaur exhibits at the Carnegie Museum, now the best in the world; Phipps Conservatory; the Warhol Museum; the August Wilson House and Cultural Center; Café Brazil and Café Brugges, and the now dominating Asian spots on Forbes and especially Murray Avenue.”

More About the Author

From the Introduction: “The Intersections of the Personal, the Political, the Academic, and Place”

My life partner for 55 years titles this endeavor, “collecting, re-collecting, and recollecting.” She is not wrong. For me and for the two of us together, preparing this account is a focused and ordered interdisciplinary “trip down memory lane” that includes sharing and comparing memories, mementos, old photos, and the contents of files and drawers unopened for years, many before hard disks or the cloud.

Until summer 2021, I did not expect drafting a historical, contextual, and intellectual memoir to occupy a place in my time or among my books. My previous personal writing addressed specific works and occasions. For example, my major books on the history of literacy, children and youth, Dallas, and interdisciplinarity led to some short, first-person essays and interviews in which I mentioned personal experiences as they were relevant. I had opportunities to publish retrospective reflections on all my major subjects but seldom on the personal, social, political, and institutional contexts of their production. My career-long public history and public humanities contributions seldom involved the personal dimensions. Little of those particular uses of my literacy appeared, by choice and by occasion.

The circumstances of my retirement and several years of adjustment to a new niche role for myself in what I call “public education” and “teaching outside the box” prepared the way (for details, see my 2021–2024 reflective essays in the Appendix). Recovery from a series of illnesses from late 2016 through 2019 left me with a fuller, more active memory reaching back to early childhood and a new search to understand critical, life-shaping relationships and influences. The almost two years of isolation during the first waves of the Covid-19 pandemic also laid the foundation.

During this period of three to four years, I achieved a clearer focus on both overarching and underlying patterns that connected my development and lived experience from childhood to my early- to mid-70s. I call this a new intersectionality. Put simply—as this book explores—these are the inextricable interconnections of personal experiences and relationships; the political, broadly defined to include life-shaping contexts and historical events, influences, values, commitments, and experiences; the social, intellectual, and political dimensions of academics and scholarship—a life of learning (to borrow the American Council of Learned Society’s phrase used for its Charles Homer Haskins Prize Lecture—see https://www.acls.org/resources/occasional-papers/) and using literacy and literacies; and the circumstances of living in six major cities from age one to the present and studying and then teaching in five universities (for more details, see citations to my 2021-2024 essays under Retirement as “Public Education,” Universities, Disciplines and Interdisciplines, Literacy and Communications, Media and Communications, Book Banning, Critical Race Theory and Education, Ohio State University, Columbus Past and Present, Ohio Issues, National Issues, and Personal).

The political embraces my experiences from childhood through the 1960 John F. Kennedy presidential campaign; the 1965–1970 grape boycott led by Cesar Chavez for the United Farm Workers; the civil rights movements from the early to mid-1960s; the anti-Vietnam War movement; student movements from the mid-1960s; women’s rights, feminism, and movements for equality, equity, affirmative action, and choice for underrepresented people; Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 presidential campaign; and much more (among an ungainly and uneven literature on the time period involved, see Kevin Boyle, 2021, and the literature cited therein).

These experiences include five years in Canada in graduate school during the Vietnam War at a time of political awakening in the northern nation. They encompass entering the academic job market at one of its lowest ebbs and at the time that affirmative action and equal opportunity were first raised. This prompted reaffirming my lifelong commitments to equity, equality, mutuality, and respect. At each major intersection, I reconfirmed my role as an egalitarian and a connector of people, learning, and issues past, present, and future in teaching, scholarship, and living. My lived experience and my active learning are inseparable from my formal education and professional historical and pedagogical practice.

The years from the mid-1960s through the 1970s were also a formative transitional period in cross- and interdisciplinary scholarship, especially in the humanities and social sciences but also in the natural sciences. Several “new histories” developed when I was an undergraduate and graduate student. Some of my most influential professors were innovators and leaders. The fields that laid the ground for my nearly 50 years of scholarly research and writing are the “new” social history, quantitative history, history of social structure, history of education and culture and especially literacy, history of children and families, history of women and gender, urban history, historical demography, theory and method in the humanities and social sciences, and interdisciplinarity itself.

Over decades, often resisting institutional as well as disciplinary pressures and divides, I strove to interrelate these fields, methods and approaches, and theoretical perspectives. I straddled departments, colleges, and other boundaries, more and less comfortably. For far too many, then and more recently, both inside and outside universities, this critical history is forgotten (for one introduction to the literature, see my Undisciplining Knowledge, 2015a; see also my Looking Backward and Looking Forward with Leslie Page Moch and Philip McMichael, 2005, and essays and books on new histories and literacy studies in the Appendix and References).

These four factors are collectively determinative. They do not stand alone. They are instructive not only for me but also for understanding the historical times from the 1950s into the 2020s, conditions of life, educational institutions, and geographical places. Together they bear examination and narration to others who may be interested in the history, individual factors including agency and relationships, academic institutions and professional life, and physical and institutional places. No one factor is independently powerful. Their intersections are complex and dynamic, sometimes contradictory and conflictual. That is among the lessons this book unveils. Together, they ground a “life course” perspective in regularly shifting times and spaces (for more on life course, see Glen H. Elder, Jr., 1974/1999; see also Elder, Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson, and Robert Crosnoe, 2003).

The surrounding, shaping context is the critical history of this era that spans the early Cold War and Eisenhower presidency through the tumultuous—and for me, life-orienting—1960s; the rise and fall of the Cold War; civil rights and voting struggles especially for Black people and members of other underrepresented racial groups, women, and LBGTQ people; the semi-normality of the 1980s and 1990s; and the startling ups and downs of the first decades of the 21st century. The period is encapsulated by the distance between Ike and the 45th president, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, between the 1960s social movements and the right-wing counterrevolution of the 2010s and 2020s, as well as popular movements including the new progressivism, Black Lives Matter, and environmentalism. These are, were, and will continue to be shaping currents.

For me, the key intersections begin with the post-World War II romance of my parents, who were born and grew up primarily as children of immigrant parents in working-class mill towns on opposite sides of the then steel capital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The first college graduate in his small business-class family, my father served in noncombatant roles in World War II’s South Pacific theatre. My mother attended college for one year.

Upon marriage in 1947, they settled in the small town of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, where they purchased a house, and where my father opened a jewelry store. I was born in a Pittsburgh hospital less than two years later, on Father’s Day, in 1949, Juneteenth before Juneteenth was generally recognized. After my first birthday, my father was diagnosed with tuberculosis and committed to a Veterans’ Administration hospital in Pittsburgh. My parents sold their house and business, and my mother and I moved into my grandmother’s small apartment near Highland Park in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. My earliest memories are etched in that apartment and occasional visits to see my father in the visitors’ room at the hospital.

Following my father’s recovery, we moved into a two-bedroom apartment in the Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh. My father joined his brother-in-law’s Braddock, Pennsylvania, jewelry business, working effectively as the manager of the Main Street store for almost the next four decades before joining a nephew’s delicatessen and catering company as manager. For the next four years, we lived in a medium-sized apartment complex on the Homestead side of the city. I began nursery school at age three and kindergarten at five, rebelling against my early classroom immersion. At that time, I was a subject in both the Salk and Sabin polio vaccine trials that originated in the University of Pittsburgh’s medical school. I was and remain resolutely pro-vaccine.

When I turned six and entered first grade in 1955, we moved into a larger two-bedroom unit in a four-plex on the other side of Squirrel Hill, one block from Linden Elementary School, which housed kindergarten through eighth grade. I spent the next eight years there, changing schools when I entered high school. Adlai Stevenson’s 1956 and JFK’s 1960 presidential campaigns influenced me, as did my parents’ moderate Democratic liberalism. Our Conservative Jewish synagogue, the now famous Tree of Life, site of an antisemitic mass murder in 2018, was nearby. In 1963, my parents purchased a small house not far from the public high school I attended.

I graduated from Taylor Allderdice High School in 1967 with honors, National Merit and advanced mathematics commendations, and a full year’s worth of Advanced Placement college credits. J. Bruce Forry, who taught me advanced-track world history in 10th grade and AP European history in 12th grade, was a fundamental influence, as was my experience on the debate team. So, too, were the campaign of Cesar Chavez for the rights of the National Farm Workers Association with its grape boycott, the civil rights movement, the student free speech movement, and the beginning of the anti-Vietnam War and the women’s movement actions.

After working for the summer in a steel mill in Homestead across the river from Pittsburgh, I entered Northwestern University on scholarships and loans with second-year standing. Chicago was a special attraction. With the presidency of my first-year dormitory, my high school political activism expanded in the turbulent second half of the 1960s. The civil rights and anti-war movements were most prominent, but student-stimulated curriculum reforms and Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 presidential campaign also galvanized me.

I majored in history with a minor in sociology. Meeting my future wife in 1968–1969, I decided to enter graduate studies in history rather than law school as my parents long urged. I had a cloudy vision of a future academic career. I drove a taxicab in Evanston and Chicago the summer following graduation and before beginning graduate school…”

Continue reading the Open Access edition of My Life with Literacy: The Continuing Education of a Historian for free at wac.colostate.edu/.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.