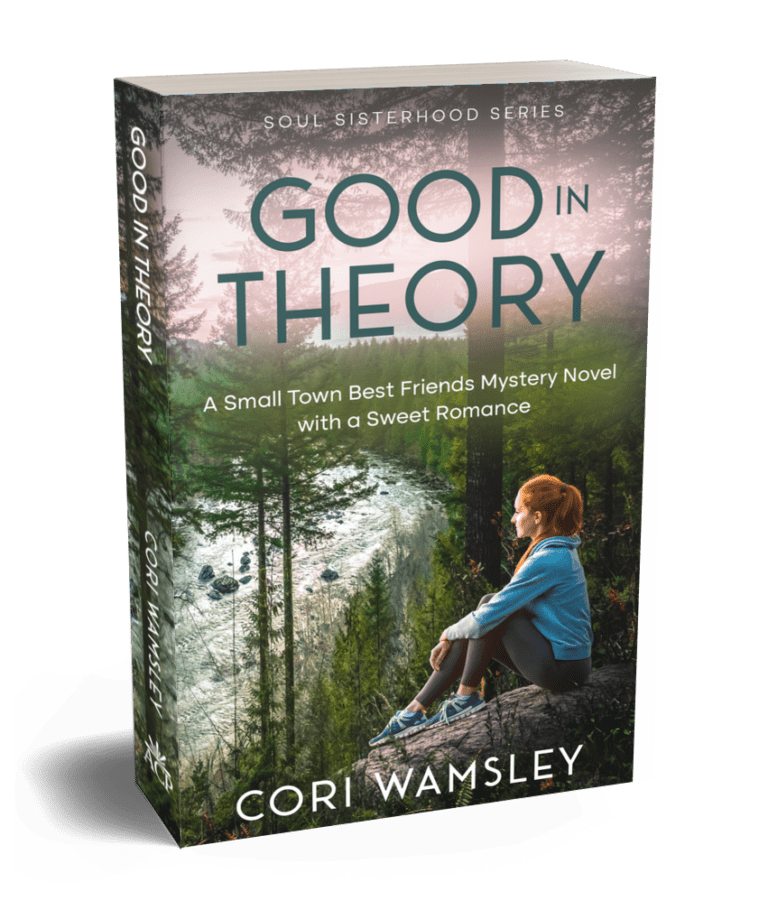

What inspired you to write Good in Theory?

My inspiration for Good in Theory came from so many different places. I used to work at a lab as a writer in the PR department, and I have a biology degree, so I easily could have pursued research instead of writing about it. I remember being so fascinated by the scientists who I got to interview for personal pieces about them. They had so many things going on in their lives outside of the lab, and I wanted to showcase that, along with the journey of an early-career professional in that world.

I love mysteries, so I wanted to incorporate an element of that into the story. The house where Gloria Brennan, a movie star, lived, provided the perfect backdrop for the mystery in modern times, and I especially loved all the speculation around her and what happened there. I find that history is as much in the “telephone-style” retelling of it as it is in the actual truth. There are so many versions of the truth that things no longer slot together properly. Until they suddenly do.

I always have a best friends theme, along with some history and adventure, but for Good in Theory, I was really drawn to the idea of a soulmate showing up for Lacey in the middle of all the chaos. Someone once told me that they used to dream about their soulmate all the time and hoped that he would eventually pop into their world. I wanted to play with that “meant to be” story without writing a full-blown romance. That’s how Lacey and Colin came to be. It also gave me an opportunity to mix in the lighter theme of love with some of the heavier and harsher things that Lacey has dealt with in her life, which kept the story from being dark and scary.

Can you tell us more about Dr. Lacey Sturm, the protagonist of your book?

Lacey is someone who is confident in herself till she starts comparing herself to others. When she’s at the lab, her group is supportive, which is important for someone early in their career, but because of some of the things a manager higher up says about and to her, it makes her doubt herself. I think this is common for people new in their professions.

A huge driver in Lacey’s life is the idea that life isn’t guaranteed. She went through something in her youth that makes her feel like she needs to keep her head down and push hard for her goals because tomorrow isn’t promised to her. Because of this, she doesn’t always pause to connect with others around her, building strong friendships, getting to know people and herself. Her best friend abandoned her years ago, and that impacts how she connects with people too. Not to mention, she is adorably awkward. She’s a little nerdy and says things that she judges herself for that are actually really funny. As she matures, she will likely embrace that part of herself as what makes people want to be around her, that casual, kind silliness that puts people at ease. Being brainy and being funny are often two hard things for a person to accept in the same body. We start to see this later on in the book with her relationships with her cousin, her lab mates, and her new friends.

How much of the story is based on your personal experiences or real-life events?

I always include little personal Easter eggs in my stories, bits of my life that were amusing or ridiculous that I want others to enjoy. An author’s life experiences always shape the way they see the world, and it’s actually pretty hard to write about things we haven’t experienced at least in part.

Yes, I do substantial research to make sure that what I’m writing is believable, though. I can’t possibly have all the experiences! For this book, a friend’s daughter who is an early-career scientist read it to help me make sure I discussed pitching journals and studying bacteria properly, since my knowledge of this is from the college biology/chemistry lab and English-department-overheard-discussions-of-journals perspective.

I threw in a few stories that someone had told me about from their lives, such as the dreams of a soulmate, jumping over a fence and realizing they were on property they shouldn’t be on, and the discussion about everyone having a price for selling out. Thinking about that last one, which stemmed from a conversation with a professor when I was in college, is what led me down the path of the main “villain” in the story. I had to wonder what their price would be. Why would they give up what they already had to do something shady? It turned into an interesting main point for the book.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book?

Often, my characters will just tell me their stories. They give me a lot of backstory. They ramble about things that may or may not end up in the book. Good in Theory wasn’t any different in that respect. But when I started Lacey’s story, I felt like a piece of the puzzle was missing till I had coffee with a friend who told me about her experience with an illness. That’s when I knew it was also part of Lacey’s story, one of the things that got in her head and has shaped who she is as an adult.

Did you encounter any surprising moments or revelations during the writing process?

I never planned to talk about Lacey’s view of her naiveté being shattered as she grew, piece by piece. It was a conversation that surprised me because I never thought about it till it came pouring out.

As we mature and realize that things aren’t perfect, our friends betray us, crimes happen down the street (not just in some big city far away), and all the other things that tend to make adults jaded by mid-life, little pieces of our innocence, our hope, our belief in the good of the world chip away like glass from a fractured snow globe. Lacey describes this feeling at one part of the book, and as I wrote it, I felt so sad for her. I always want to believe in the good of others, that most people are decent, kind, and caring humans, etc., but I understood her sentiment. As the story progressed, I found opportunities to meld some of those glass pieces back together and let her talk about it, like restoring faith in humanity. That part was incredibly hopeful and healing.

How do you hope readers will connect with the story and its characters?

I hope that my readers will see a little of themselves in all the characters. I never write anyone who is perfect, and even some of the peripheral characters make mistakes. One of the reasons I love writing from first-person perspective is that we get to be introspective with that character and really dive into what’s going on in her head. I hope that everyone who reads this story can find themselves there.

What message or theme do you want readers to take away from Good in Theory?

We all have preconceived notions about people, and we should be open to them shattering them. When I started writing this book, I did something a little differently from what I normally do. I began with an outline (which is normal), but then I asked what Lacey and Saoirse believe about each other that isn’t true.

Their beliefs come from outdated experiences with each other. They were best friends from childhood through most of high school, but ten years later, with no contact in between, they had to recognize that they are completely different people. For Lacey, it was really easy for her to see immediately that Saoirse isn’t who she used to be because the change was so drastic: she used to be irresponsible and self-centered, always looking for that next literal or figurative high, but as an adult, she had learned to care beyond herself and was actually quite mature and giving.

Saoirse, however, thought things about Lacey that weren’t actually true even when they were younger. She had witnessed Lacey starting to go through a difficult time in her life and then left the scene for several years. And she left with assumptions about Lacey that she never bothered to question. Plus, phe never got to see how Lacey came through that time, how she matured, and the bigger effects that this difficulty had on her personality. We carry what we’ve been through with us, and we can either drag that burden along or use it as a tool for our growth. As much as Saoirse had matured, she still fixated on cues in Lacey’s speech that told her that she hadn’t changed from the image that Saoirse had been carrying around with her, an image that was a reflection of some of Saoirse’s deeper core wounds from when she was younger. She was projecting her own pain and beliefs onto Lacey. It was something she still hadn’t healed, so she saw it in others because she considered it a flaw.

I want readers to see this and understand that we can be open to reading people but also to listening to them and looking for the best in them, as well as ourselves. Saoirse needs an extra minute to do that.

I also want the reader to believe in magic and the unknown and to stop white knuckling things that they feel they need to control, especially those that they can’t. It’s a hard lesson for Lacey, and for most of us, but if we can step back and just maintain control over what we actually have the ability to control, I think we will all be happier.

Good in Theory is available for preorder at https://amzn.to/3EqLXk2.

About the Author

Cori Wamsley is an award-winning author of best friend stories with a side of romance. She has written 11 books, including Braving the Shore and The Treasures We Seek, which were lauded with The Author Zone Award for excellence in fiction in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Her stories are enchanting and witty, woven with the magic of self-discovery, history, adventure, and falling in love.

Connect with Cori at www.coriwanmsley.com or on Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok.

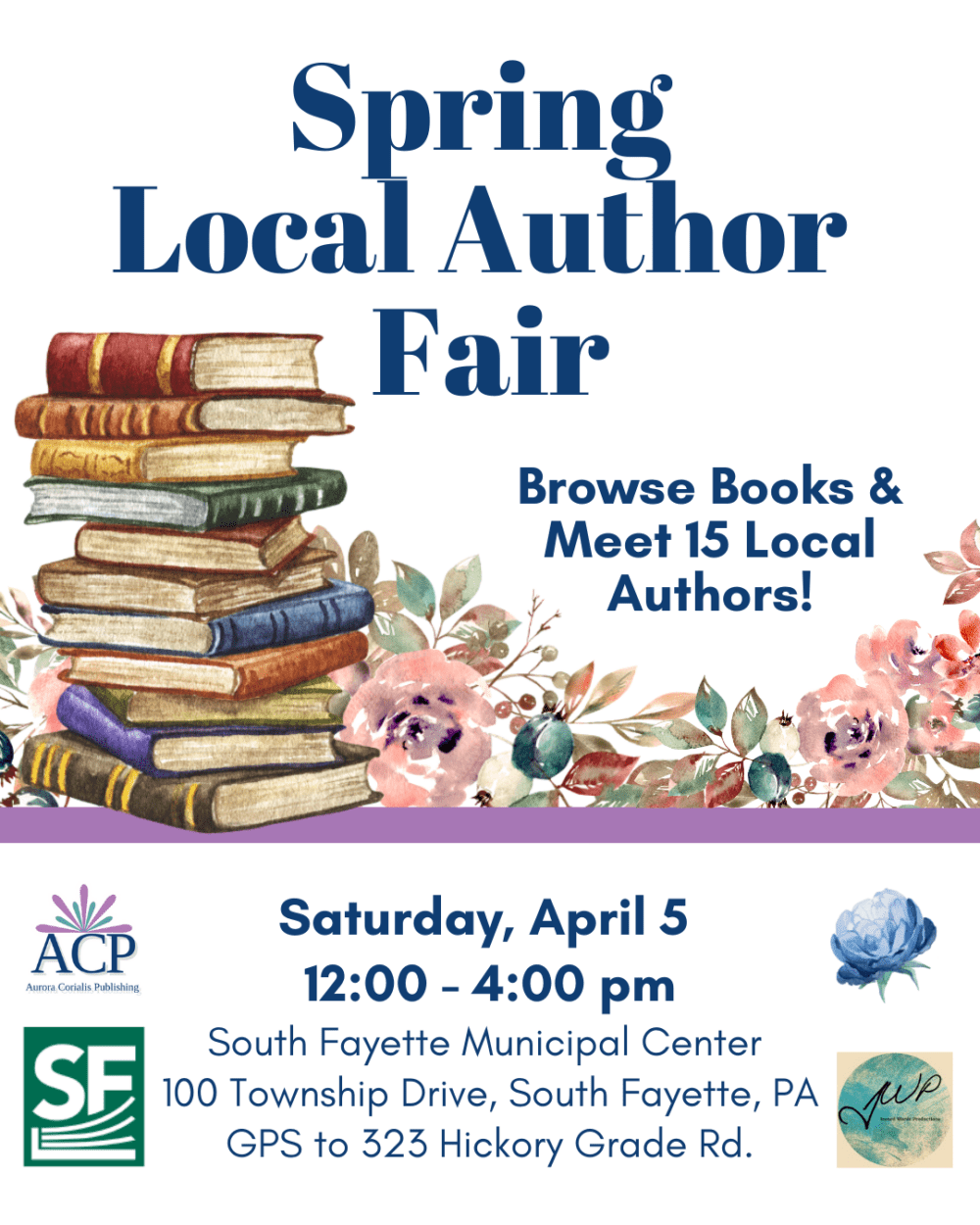

Meet Cori and other local authors at the Spring Local Author Fair!