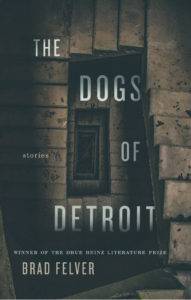

Winner of the 2018 Drue Heinz Literature Prize for short fiction!

“Felver’s writing is sharp and insightful. His stories evoke the style and themes of writers ranging from Richard Russo to Rick Bass to Andre Dubus III and, in the particularly brutal surrealist title story, ‘The Dogs of Detroit,’ Cormac McCarthy.” – Kirkus Reviews

University of Pittsburgh Press: “The fourteen stories of Brad Felver’s The Dogs of Detroit focus on grief and its many strange permutations. This grief alternately devolves into violence, silence, solitude, and utter isolation. In some cases, grief drives the stories as a strong, reactionary force, and yet in other stories, grief evolves quietly over long stretches of time. Many of the stories also use grief as a prism to explore the beguiling bonds within families. The stories span a variety of geographies, both urban and rural, often considering collisions between the two…”

Don’t miss out: Join University of Pittsburgh Press for a free reading with 2018 Drue Heinz Literature Prize winner, Brad Felver at City of Asylum on Wednesday, September 12!

Felver will also be introducing Joyce Carol Oates for Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures (!) on September 24.

About the Author: Brad Felver is a fiction writer, essayist, and teacher of writing. His honors include the O. Henry Award, a Pushcart Prize special mention, and the Zone 3 Fiction Prize. His fiction and essays have appeared widely in magazines such as One Story, New England Review, Hunger Mountain, and Colorado Review. Currently he serves as lecturer and associate chair of the English department at Bowling Green State University. He lives with his wife and kids in northern Ohio.

“The Dogs of Detroit”

from The Dogs of Detroit

Nights, when Polk cannot hunt the dogs, he instead attacks his father. He has grown to crave the hot pain spreading over his face, the bulging of his knuckles when they connect with bone. His father fights back just enough. They roll around on the floor, struggling and grunting, sneaking in shots to the ribs and the temples. When they tire, they each collapse, wheezing, moaning. They rub their flushed faces and lick away the blood pooling on their gums and retreat to their corners. No resentment or words, as if they are not punching each other, not exactly. A narcotic hunger being fed, one which brings no joy, but rather is a conduit for torment.

Nights, when Polk cannot hunt the dogs, he instead attacks his father. He has grown to crave the hot pain spreading over his face, the bulging of his knuckles when they connect with bone. His father fights back just enough. They roll around on the floor, struggling and grunting, sneaking in shots to the ribs and the temples. When they tire, they each collapse, wheezing, moaning. They rub their flushed faces and lick away the blood pooling on their gums and retreat to their corners. No resentment or words, as if they are not punching each other, not exactly. A narcotic hunger being fed, one which brings no joy, but rather is a conduit for torment.

After their fights they lay there, panting, blinking back tears, and only then does Polk confide in his father. He lists off the revenges he wants to take on the universe. He imagines the worst things possible: toddler coffins, flayed penguins, pipe bombs in convents, napalm in orphanages. He hates himself for it, his selfishness, his appetite for sloppy justice. Always he ends up wondering the same thing: Does God hate me more than I hate God?

His father reaches for Polk’s hand, but Polk pulls away. No touching unless it is to create violence. “Patience,” his father says. “We must learn grief.”

After school, Polk hunts. He ranges across the urban wilderness of the East Side, ducks through the cutting winds off St. Clair. He lugs a Winchester bolt action by the barrel, dragging the stock on the ground, leaving a crease in the snow. He tracks dog prints through the industrial fields, through the brambled grasses and split concrete and begrimed snow. Through decomposing warehouses and manufacturing cathedrals which nature has reclaimed. Hundreds of deserted acres. These are wild dogs he kills, no longer bear any trace of domestication. Few people left, but the dogs—thousands of dogs, abandoned during this great human exodus. There is no Atticus Finch to blast the rabies from them, no little girl to drag them home by the scruff to her father and say May we please? As all else crumbles, the dogs remain.

After school, Polk hunts. He ranges across the urban wilderness of the East Side, ducks through the cutting winds off St. Clair. He lugs a Winchester bolt action by the barrel, dragging the stock on the ground, leaving a crease in the snow. He tracks dog prints through the industrial fields, through the brambled grasses and split concrete and begrimed snow. Through decomposing warehouses and manufacturing cathedrals which nature has reclaimed. Hundreds of deserted acres. These are wild dogs he kills, no longer bear any trace of domestication. Few people left, but the dogs—thousands of dogs, abandoned during this great human exodus. There is no Atticus Finch to blast the rabies from them, no little girl to drag them home by the scruff to her father and say May we please? As all else crumbles, the dogs remain.

And then one day: his mother’s tracks, long and narrow, weight on the outside ridges. Keds. She always wore Keds. She has been gone two months now, disappeared. She was there when Polk went to school, sitting at the kitchen table, sucking on a menthol, gone when he got home. But these are her prints. He knows them. They mix in with the dog prints, as if she has joined them. Perhaps has been hunted by them, perhaps something else altogether.

Eventually, he thinks, I’ll whiten the canvas, leaving only her tracks. Eventually, a pattern will emerge. But with each dog he kills, his palate mutates: joy. The heavy thunk of bullet piercing a ribcage. Eliminating a contagion. A growing pleasure to be found in mindless violence. Carcasses left to rot, to ravage by predators. Always there seem to be more dogs, like a muscle in need on constant stretching.

At school, he sits alone. He is a large boy, the largest in the junior high school, his feet flapping on the concrete hallways as if they were made for an adult but then attached to him instead. The art teacher, Mrs. Roudebush, prods him to rejoin the world. More pictures of mom, Polk? More charcoal? Why not try the acrylics? Some greens and yellows and magentas.

“No thank you,” he says. His face remains placid, all its topography flattened, grown numb, unable to flex. He refuses to look up, and she soon wanders away to check on other students.

After school he walks home to their house on the East Side, then through the tunnel of tall grasses, which have swallowed up all but the second story where they never go. Collapsed staircase, plywood windows, a contentedness in allowing it to erode.

These winter days the sun never truly rises. No direct light, no marbled streaks or roiling clouds, just a vast gray slab. Slowly, the night mottles into blued steel as if other colors have not yet been discovered. He grabs the Winchester and sets off, follows the freshest of the dog prints as far as they will take him, across the freeway and toward the old Packard compound, its remnants. He nestles onto a hillside, his favorite perch, downwind. A sniper in Stalingrad. He takes down two dogs quickly, the echoes of the rifle shots ballooning around out in waves. The sun droops. A mangy pit bull trots into the field, and Polk takes it down, the round ripping through the dog back near its haunches, and it stumbles, tries to limp away, dragging its paralyzed legs. For several minutes it struggles forward and Polk watches. Then it stops moving. Polk trudges home, stomping wide holes in the snow, the butt of the Winchester digging a crease behind him. His mother’s prints, which had been clear the day before, have vanished, taken by the wind.

The Dogs of Detroit is copyright © 2018 Brad Felver. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and the publisher, University of Pittsburgh Press, and should not be reprinted without permission.