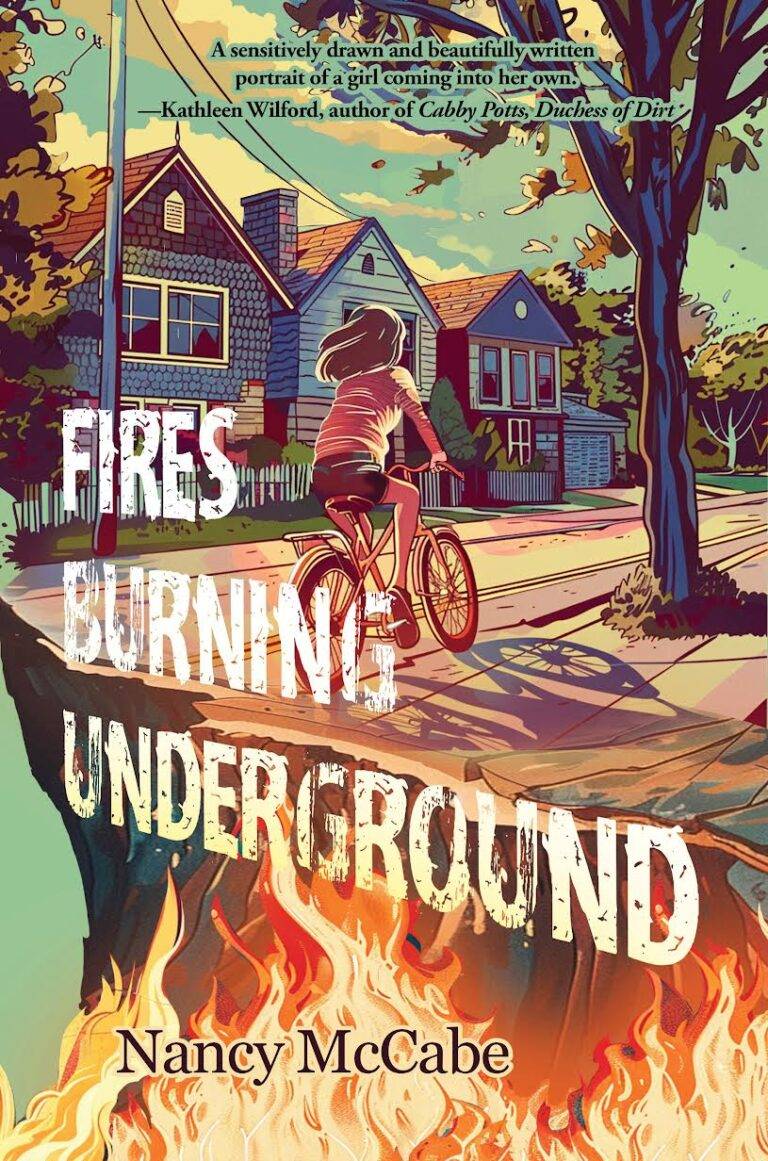

From the Publisher: “It’s Anny’ s first day of middle school and, after years of being homeschooled, her first day of public school ever. In art, Larissa asks what kind of ESP is her favorite: telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition, or telekinesis? Tracy asks how she identifies: gay, straight, bi, ace, pan, trans, or confused? Thus kicks off a school year for Anny in which she’ll navigate a path between childhood and adolescence, imagination and identity. In a year of turmoil and transition, with a new awareness of loss after the death of a friend, Anny struggles to find meaning in tragedy, to come to terms with her questions about her sexuality, and to figure out how to negotiate her own ever-shifting new friendships. And when her oldest friend’s life is in danger, she must summon up her wits, imagination, and the ghosts that haunt her to save them both…”

More info About the Author: Nancy McCabe is the author of nine books, most recently Fires Burning Underground (Fitzroy/Regal House), the comic novel The Pamela Papers: A Mostly E-pistolary Story of Academic Pandemic Pandemonium (Outpost 19, 2024), the YA novel Vaulting through Time (CamCat 2023), and the memoir Can This Marriage Be Saved? (Missouri 2020). Her tenth book, a craft book about the intersections between artistic and therapeutic writing, is under contract with University of New Mexico Press. Her work has received the 2024 Next Generation Indies Award for humor/comedy, a Pushcart Prize, and ten recognitions as notable in Best American anthologies. She directs the creative and professional writing program for the University of Pittsburgh at Bradford and teaches in the low-residency graduate writing program at Spalding University.

Author Site “Yes, there are fires, but there are also ‘codes’ in McCabe’s compelling middle-grade story about Anny and the many codes she tries to decipher as she navigates fitting into a new school, old and new friendships, questions about sexuality and identity, and those that inform her parents’ lives.”–Susan Campbell Bartoletti, author of THE BOY WHO DARED and HITLER YOUTH: GROWING UP IN HITLER’S SHADOW

“A sensitively drawn and beautifully written portrait of a girl coming into her own.”—Kathleen Wilford, author of CABBY POTTS, DUCHESS OF DIRT

“Nancy McCabe deftly taps into the adolescent mind and voice of her character, Anny, with all her angst, hopes, fears, questions, and constant ups and downs. Young readers of today’s world will readily identify with Anny’s roller coaster of emotions.”—Edith Hemingway, author of THAT SMUDGE OF SMOKE and ROAD TO TATER HILL

“Spirits prowl at the corners, but tender vulnerability and small rebellions make the haunting, beating heart of Nancy McCabe’s middle-grade novel.”—Independent Book Review, starred review

“Original, imaginative, deftly crafted, emotionally engaging, and a fun read from start to finish, Fires Burning Underground by author Nancy McCabe . . . is an especially and unreservedly recommended pick for elementary school, middle school, and community library Contemporary Fiction collections for young readers ages 9-12.” —Children’s Book Watch

“Readers who are facing similar angst about growing up may find something to relate to in Anny’s story and the courage to ask their own questions.”—Booklist

This is your debut novel for middle grade readers. Why did you choose to write for that audience?

As the author of several nonfiction books for adults and novels for adults, young adults, and now middle graders, I feel like genre chooses me rather than the other way around. I’m a voracious reader in a wide range of genres and categories, which helps give me the tools for trying out new genres. I started writing Fires Burning Underground as a memoir, a coming of age story. But I needed to free myself to make things up and update the story rather than adhering to my own experience, and the themes that emerged as I wrote felt particularly appropriate to middle grade readers: friendship, sexuality, identity, creativity and imagination, grief, and religious intolerance. I wanted to write a story that addresses the universal struggle of bridging the gap between childhood and adolescence and seeking to understand the complex possibilities and challenges surrounding friendship and love, creativity and mortality.

Did you take inspiration from your own childhood in writing this book?

Very much so—my sixth grade year began and ended with fires, as does the story. The first was a house fire that killed a kid I’d known my whole life, and the second destroyed most of the contents of the house next door to mine before the firefighters were able to put it out. The loss of the boy I knew was my first confrontation with the death of a peer, and I had nightmares for weeks.

But in the book, I also conflated the terrors of that year with a magical friendship from my seventh grade year. We were fascinated by the supernatural and drawn to creative activities—music, art, writing, crafts, projects like creating secret codes, a treasure hunt for a friend, a carnival.

So the book is about the darker sides of imagination—especially the terror I struggled with—and the lighter side, imagination as a saving grace. While I made up many elements, compressed time, and conflated some experiences to make the story more dramatic, the core of the story comes from my own childhood.

What challenges did you face in writing for this audience?

Finding Anny’s voice! She was in many ways based on me when I was twelve, but finding my way into the voice of a twelve-year-old took a lot of work and revision. I read and reread many middle grade novels to examine their voices, reread childhood diaries to refresh my memory about what I’d sounded like at that age, listened to my daughter and her friends, talked to my students about how they’d seen themselves at that age.

As I went deeper into Anny’s voice and character, something in my subconscious was activated and I started hearing her speak to me. I began to understand that one of her struggles has to do with how she identifies sexually, something I wanted to examine in an age-appropriate way. Like me at that age, she places a high value on female friendship and doesn’t relate to her friends’ interest in boys. She comes to identify as queer, a label that wasn’t on my radar when I was that age but very much fits the choices Anny finds herself making even while she comes up against the narrow religious beliefs of her family. I began to understand that the story is ultimately about Anny’s self-definition and resistance to labels and expectations, her need to figure out how she wants to define herself.

I hope that Anny’s journey will serve as a template that offers young readers permission to be themselves, process their own losses, and consider the many different ways we can be fulfilled in relationships. I hope that it will empower them to resist others’ definitions and refuse to cave to others’ expectations, even when that leads to strife.

Can you give us an excerpt from the book?

At midnight, I bolt awake from nightmares and punch out my hands to touch the blankets and bedside table, expecting them to crumble to ashes. Waking a little farther, I fumble for the lamp switch. The room springs to life in the light, all of my furniture where it belongs, the clothes I finally laid out for school draped over a chair. Everything is the same. I’m still alive. But my heart won’t stop jackhammering against my chest. I feel dizzy with panic.

The next thing I know, I’m on my feet, skittering down the hall to bang on my parents’ door. A fan whirs and blankets rustle and then I hear calm, muffled voices. “What is it?” Mom calls.

Now I’m fully awake and back to my senses. I immediately feel dumb. I haven’t pounded on my parents’ door in the middle of the night since I was little. Sometimes, Dad used to come sit beside my bed and stroke my hair when I had a bad dream. His big hand smoothed the strands, tugging gently, and it was strangely comforting to feel how firmly they were rooted to my head. Sometimes, instead, Mom used to come lie down beside me till I fell asleep.

But that was a long time ago. I’m too old for any of that now. Never mind, I want to call, but I’m all clammy, fear still gripping me like a tightening fist.

The lock releases. Mom slips out, bringing with her cold air from a window air conditioner, as if she’s blown into the hall. She smells like the cold cream that masks her face. She smells like powder from a pink puff, and Ivory soap, and mint toothpaste, the smells of the everyday world where shadows are just tricks of light, not ghosts.

“It was nothing.” As my fear fades, my embarrassment rises. “Just a nightmare.”

Mom escorts me back to my room. She’s wearing a pink silk robe and toting her big paperback study Bible. While I was panicking in the hall, she was tying her sash, brushing her teeth, and locating the Bible.

Lately, whenever she starts reading or quoting scripture, I feel this intense dread and shame. I desperately want her to stop. “I’m okay, really,” I say now, but she settles herself on the edge of my bed, licking a finger and whisking through tissue-thin pages. The cold cream makes her seem like someone carved in marble. “I’m fine,” I try again.

“I know it’s scary, what happened to Robert,” she says.

Now I’m not just embarrassed, I’m mortified, the way I was when she decided it was time to have “the talk” about sex when I was ten. It was totally awkward, and anyway, I already knew all about sex from Tracy, who I met in Girl Scouts. She thinks of herself as very worldly compared to me because she has always gone to regular school and she always has crushes on celebrities, old guys who are in their twenties and thirties.

Now, it’s weird the way the word dead makes me feel as uncomfortable as the word sex, like a word too terrifying to say aloud. The word grief also feels too complicated and personal, a word I haven’t earned. I didn’t know Robert that well, and I wasn’t that nice to him. I wasn’t mean, either. I just didn’t pay attention to him.

“You don’t have to be afraid of death.” Mom flips open her Bible and starts reading. “‘Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground, apart from the will of your Father. And even the very hairs on your head are all numbered. So don’t be afraid, you are worth more than many sparrows.’”

Then why, I wonder, didn’t God protect Robert?

I slide down under the covers, hiding my face, pretending to drift off to sleep, regretting that I broke the resolution I made months ago not to ask Mom any questions with answers that might involve a Bible. Like what happened last year, when Tracy told me that maybe I don’t like boys because I’m gay.

“I’m only twelve,” I answered, but Tracy rolled her eyes, because she was several months younger than me and she was obsessed with boys, so she thought everyone was supposed to be.

“How does a person know if they’re gay?” I asked Mom, who’d laughed. “Oh, you’re just a late bloomer,” she said. “Your hormones haven’t kicked in yet.”

“But what if I am?” I asked, and she got more serious.

“It’s not like it’s just something that people are. It’s something that people choose to be when they’re not right with God. Our church believes that homosexuality is a sin.” And she’d started reading Bible verses, with words like unnatural and abomination, words that made my stomach feel tight.

I tuned her out. If I’m gay, didn’t God create me that way? But how do I know if I am or not? And when do I have to decide for sure? And if I am, does that mean my parents will stop loving me? Will they kick me out? Will I end up homeless, sleeping on the concrete blocks under the metal girders of the turnpike bridge, shivering in the cold as cars roar overhead?

Now, as Mom sits on the edge of my bed and reads verses about death that she thinks will be comforting, I feel more confused than ever. Maybe I didn’t like Robert like that because I don’t like boys, but I’m not sure if I like girls that way, either. I’d rather hang out with girls, but last year, when Tracy wanted me to pretend to be a boy and practice kissing with her, I said, “Ooh no.” So does that mean I’m straight, or gay, or just not anything?

Mom stops reading and says, “Do you feel better?”

Eyes still closed, I mumble something deliberately incoherent. I know she’s going to leave, go back to her room and close the door, and a part of me wants her to but another part is terrified of being left alone in the dark again.

She rises and lays the Bible on the nightstand. I see her, through my half-closed eyes, push aside my library book because, she always says, you should never put anything on top of a Bible. “I’ll leave this here in case you need it,” she says.

After her bedroom door closes softly, I lie awake as cars from the turnpike beam their lights along the wall. What if God wills me to die the same way he can will a sparrow to drop to the ground in mid-flight?

I wish I had a best friend, the kind of BFF I read about in magazines, the kind of friend girls in old books have, called embarrassing old-fashioned names like soulmates, kindred spirits, and bosom buddies. “Bosom,” I used to repeat, laughing hysterically, when I was eight or nine and Mom read aloud Anne of Green Gables. I wish I had a friend I could talk to who would help me sort all of this out. I hope I make a friend like that at school. I imagine telling my new friend all about Robert and my nightmares and what Mom said about being gay.

Finally, I drop off to sleep and dream that I am walking down the hall of a school where I don’t know anyone, while outside birds rain down from the sky.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be republished without permission.