From the Publisher: “On a July morning in 1953, truck driver Lester Woodward was found just off the Pennsylvania Turnpike slumped over in his cab, dead from a gunshot wound to his head. Three days later, another truck driver, Harry Pitts, was found murdered in similar fashion, with ballistics confirming that it was the same gun. Fear spread among the trucker community as many armed themselves and troopers began to patrol sleeping drivers. After a third shooting in Ohio, near the end of the turnpike, national media began referring to the killer as the ‘Turnpike Phantom.’ Police leads led to John Wesley Wable as the suspect, and despite leading cops on a wild chase in New Mexico, he was arrested and tried for murder. Author Richard Gazarik details the bloody crimes, harrowing manhunt, intense trial and eventual execution of Pennsylvania’s Turnpike Phantom Killer…”

More info About the Author: Richard Gazarik, author of The Pennsylvania Turnpike Phantom Killer, is a former journalist who also has written Black Valley: The Life & Death of Fannie Sellins, Prohibition Pittsburgh, Wicked Pittsburgh, which comes out as an audio book in October by Tantor Media, The Mayor of Shantytown. The Life of Father James Renshaw Cox and Swinging in the Steel City. A History of Pittsburgh Jazz.

Interview with Richard Gazarik

What drew you to John Wesley Wable’s story?

I remembered as a new reporter at the newspaper where I was working listening to the old timers talking about a sensational murder trial in Greensburg in the 1950s. I covered murders and murder trials for decades so I thought I’d investigate John Wesley Wable, dubbed the phantom turnpike killer. I’m not a big fan of true crime stories but this story intrigued me because of the speed with which Wable was caught, convicted and executed.

How much research did you do?

Well, I thought the book would be easy to write but I discovered there are no records of the trial. That made the research difficult. The transcript of the trial and supporting legal filings are missing from the Westmoreland County archives so I had to read accounts of the murders, investigation and trial from newspapers in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and New Mexico.

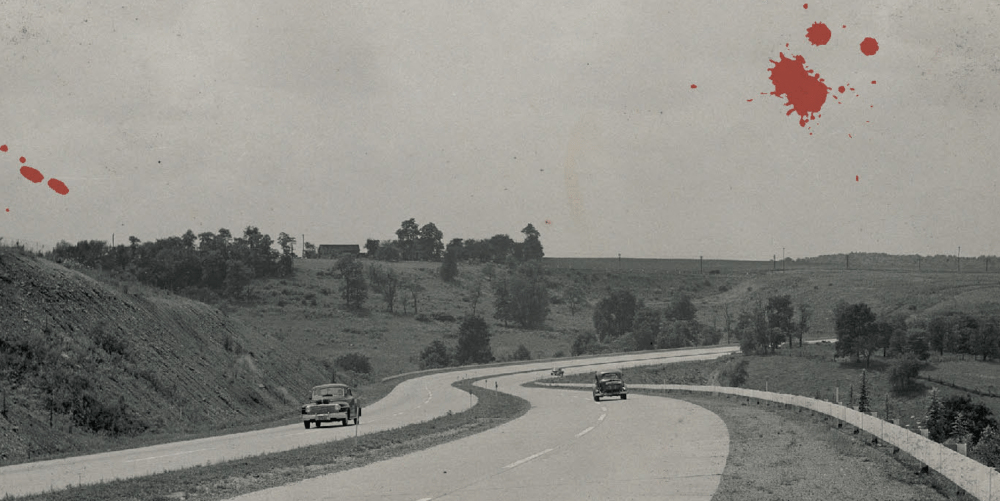

In your book, the information about the turnpike itself is really interesting…

Yes. The book, in a sense, is also a history of the turnpike. I was surprised to learn that there were no speed limits when the pike first opened. There were no barriers separating the east and westbound lanes. It wasn’t until there was an increase in fatal traffic accidents that speed limits were imposed and the state police presence was expanded to patrol the highway.

What motivated Wable to kill truck drivers?

Prosecutors never established a motive. It was first thought that robbery was the reason for the killings. Then investigators dismissed that motive. Wable was a suspect in two other turnpike homicides including one at the Monroeville interchange. Although he was questioned about the killing, he was never charged… even though the police composite sketch bore a strong resemblance to Wable.

You write a great deal about the death penalty…

I do, because death by hanging, and electrocution, were routine punishments for first degree murder. There was little debate at the time about the constitutionality of the death penalty, but there was about whether hanging was more humane than electrocution. If Wable had been sentenced to death today, he likely would have spent years, if not decades, on death row.

Excerpt

If It Bleeds, It Leads

Crime stories have long been a staple of newspapers, and reporters were drawn to the turnpike killings like sharks are attracted to blood in the water. Editors dubbed the suspect the “Phantom Turnpike Killer,” and the murders dominated the news coverage for the rest of the year as the investigations continued. The Puritans of early Massachusetts, those strait-laced, somber-looking clerics, stood on the gallows next to an individual who waited to enter eternity at the end of a rope as the black-robed minister delivered an “execution sermon,” recounting the details of the crime and the condemned’ s miserable life, according to Mortal Remains. Death in Early America. Ministers were “gray old Gospellers, sour as midwinter,” according to a description of Puritan clergy in Two Centuries of Costume in America.

The sermons were, in a sense, true crime narratives that contained details of the crime and perhaps the prisoner’s confession that were accompanied by a fire and brimstone oration based on passages from the Bible. The sermons had all the elements that comprise true crime books today—interesting characters, strong storytelling and details of the crime that appealed to people’s fascination with evil. The sermons made ministers like Increase and Cotton Mather, Samuel Danforth and Benjamin Coleman the first true crime authors. Although the sermons were aimed at sin and salvation, some ministers, such as Cotton Mather, made them appeal to a broader audience by adding “a dollop or two of sensationalism.” The sermons were not meant to titillate observers but to instill in them the fear of God. Puritan ministers viewed the sermons as an opportunity to save the souls of the thousands who attended the hangings and served to justify the righteousness of the execution.

The sermons had the opposite effect. They appealed to the crowd because they contained the condemned individual’s confession, lurid details of the crime and the state of the prisoner’s mind before they died. To appeal to a broader audience, the sermons were published by the ministers and sold at a low cost to a public who craved the details of the execution. In 1635 in England, John Reynolds published The Triumphe of God’s Revenge Against Execrable Sinn of Murther, a compilation of tales about executions. “They certainly pull you in. Human nature doesn’t change. There is morbid fascination,” according to “Guide to the Gallows” in The Harvard Gazette. The execution sermons are part of a collection, “Dying Speeches and Bloody Murders” at the Harvard Law School Library. The first known execution sermon was delivered in 1674 by Samuel Danforth and was titled “The Cry of Sodom Inquired Into.” It was delivered at the execution of a man who was hanged for bestiality.

“You pity his youth and tender years, [but]I pray, pity the holy law of God, which is shamefully violated…pity the land, which is fearfully polluted and defiled.” To the Puritans, executions were a way of avenging God for the sins of man. Increase Mather in Massachusetts delivered a warning at the execution of a convicted murder in 1686, saying that the state had a legal and moral obligation to kill those who “violated the laws of God,” according to the book Hanging Between Heaven and Earth, Execution Preaching and Theology in Early New England. “One murderer unpunished may bring guilt and a curse upon the whole land, that all the inhabitants of the land shall suffer for it,” Mather warned.

The Puritans wanted the sermons to impress upon the witnesses the dangers of sin and to serve as a deterrence to future crimes. The prisoner was expected to participate in this theater of death by confessing, seeking repentance and asking for God’s forgiveness. The sermon, containing the last mutterings of the executed and details of the crime were printed and sold to a populace eager to read about how the condemned behaved before dying. A condemned person’s last words were likely written by a minister or a public official who spent time with the prisoner before his death. Ministers later added details of the crime and execution, which were read aloud to the crowd. The sermons included the word-for-word confession and verbatim conversations between the condemned and his jailers, because the Puritans realized they could avert future sin if they sensationalized the details to make an impression on individuals. In one sermon, the confession of a man who was about to hang for murdering his family described in detail each step he took and the order in which the victims were murdered. In another case, a man who was about to die for rape and murder detailed how he hid in the woods and ambushed a young woman.

“The certainly pulled you in,” said Mary Person, an archivist at the Harvard Law School Library, which compiled a collection of execution sermons, “Dying Speeches and Blood Murders” In Pennsylvania, chapbooks, known as “gallows literature,” were inexpensive and small—four by eight inches—and ran between eight and twelve pages in length. The pages were published in boldface type and often contained woodcuts of the gallows and coffins, with figures hanging at the end of ropes. John H. Craig’s execution was memorialized in an 1818 chapbook, which heralded, “The confession of John H. Craig and executed on Saturday, the sixth of June 1818, for the murder of Edward Hunter, Esq., as stated by him after trial.” True crime stories took hold during the Elizabethan era. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote was the first of modern crime books that detailed the 1959 murders of the four members of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas. Capote merged journalism and creative writing in a nonfiction book that read like a novel. In Cold Blood was followed by Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, an account of the Manson family murders; Joe McGinnis’s tale of green beret captain Jeffrey MacDonald’s slaying of his wife and two children; Jack Olsen’s Salt of the Earth: One Family’s Journey Through the Violent American Landscape; and Ann Rule’s book on serial killer Ted Bundy, The Stranger Beside Me.

True crime books were a far cry from early newspaper accounts of murders, trials and executions. A reporter for the Uniontown Morning Herald in Pennsylvania who witnessed the execution of John Kozial in the electric chair in 1933 was less than literary when he wrote, “In a flash, it was over— John William Kozial had gone to a higher court to receive a sentence that is to last through eternity.” George Edward Stevenson killed a constable in Pennsylvania, fled to West Virginia and was cornered by a posse, shot and left paralyzed. A reporter for the Pittsburgh Press wrote in 1925 that “Stevenson was paralyzed from the waist down, and four guards had to carry him on a stretcher and lifted him onto the electric chair, where he was soon paralyzed from the head down.”

Crime stories first surfaced in the 1830s, when Benjamin Day of the New York Sun titillated readers with tales of murder and mayhem. “If it bleeds, it leads” became the editorial philosophy of newspapers. Edmund Pearson was a Harvard-educated librarian who defined “true crime” with his writings about murder and mayhem. Even the Bible is considered a true crime book, with Old Testament tales of murder and violence starting in Genesis with the story of Cain and Abel, the sons of Adam and Eve. Cain slays his brother and is punished by being forced to wander the rest of his life. Amnon, a son of King David, is slain for raping his half sister. Even God doesn’t escape murder accusations. He destroyed the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and turned Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt. He also killed the first-born sons of Egypt and destroyed the entire Egyptian army in the Red Sea.

Ever since Jack the Ripper terrorized London, readers have been drawn to the gory details of murder, which spawned a tabloid culture that focuses on sensational murders and celebrity gossip. The best example of this form of journalistic culture was the 1983 New York Post headline “Headless Man Slain in Topless Bar.”

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.