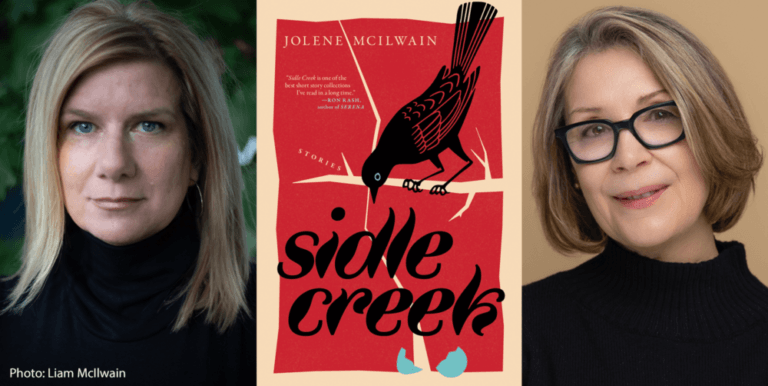

“Sidle Creek is one of the best story collections I’ve read in a long time.” –Ron Rash, New York Times bestselling author of Serena

From the Publisher: “Set in the bruised, mined, and timbered hills of Appalachia in western Pennsylvania, Sidle Creek is a tender, truthful exploration of a small town and the people who live there, told by a brilliant new voice in fiction.

In Sidle Creek, McIlwain skillfully interrogates the myths and stereotypes of the mining, mill, and farming towns where she grew up. With stories that take place in diners and dive bars, town halls and bait shops, McIlwain’s writing explores themes of class, work, health, and trauma, and the unexpected human connections of small, close-knit communities. All the while, the wild beauty of the natural world weaves its way in, a source of the town’s livelihood – and vulnerable to natural resource exploitation.

With an alchemic blend of taut prose, gorgeous imagery, and deep sensitivity for all of the living beings within its pages, Sidle Creek will sit snugly on bookshelves between Annie Proulx, Joy Williams, and Louise Erdrich.”

More info About the Author: Jolene McIlwain’s fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appears in West Branch, Florida Review, Cincinnati Review, New Orleans Review, Northern Appalachia Review, and 2019’s Best Small Fictions Anthology. Her work was named finalist for 2018’s Best of the Net, Glimmer Train’s and River Styx’s contests, and semifinalist in Nimrod’s Katherine Anne Porter Prize and two American Short Fiction‘s contests. She’s received a Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council grant, the Georgia Court Chautauqua faculty scholarship, and Tinker Mountain’s merit scholarship. She taught literary theory/analysis at Duquesne and Chatham Universities, and she worked as a radiologic technologist before attending college (BS English, minor in sculpture, MA Literature). She was born, raised, and currently lives in a small town in the Appalachian plateau of Western Pennsylvania with her husband, son, and two rescue cats.

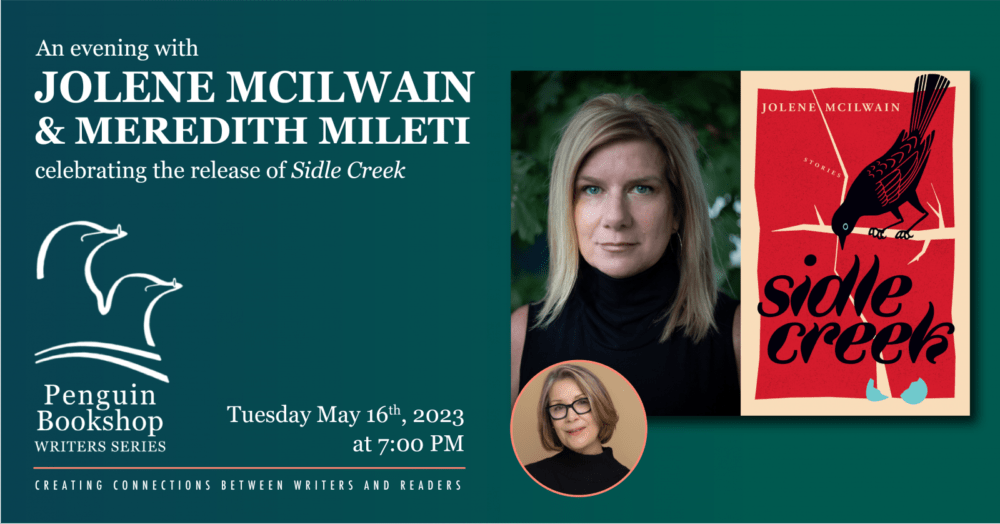

Author Site Don’t miss out: Penguin Bookshop is presenting “An Evening with Jolene McIlwain & Meredith Mileti” on May 16th as part of their Writers Series!

Event “[An] impressive debut collection spotlights the hard-edged people who call rural western Pennsylvania home . . . McIlwain’s reverent regard for the natural world makes her a worthy successor of Annie Dillard.” —Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

“Riveting debut collection . . . a showcase of vivid, empathetic stories that defy the stereotypes about her [McIlwain] rural Western Pennsylvania . . . Sidle Creek is a rare gem, a compelling blend of nature and humanity perfect for fans of Barbara Kingsolver’s Prodigal Summer and Daisy Johnson’s Fen.” —Shelf Awareness

“There’s a subterranean wisdom threading through the ground of these stories, creating deep links, pulling stunning parts into a still more stunning whole. Jolene McIlwain gives us the kind of truths that can only come from knowing her subjects–people, animals, and landscape alike–entirely and truly, in all their darkness and light. An extraordinary debut from a writer of rare insight and lyric power.” —Clare Beams, author of The Illness Lesson

Meredith Mileti: Congratulations on the upcoming publication of Sidle Creek, Jolene. I am so excited that this wonderful, rich, evocative collection will soon be in readers’ hands! Tell us what the journey has been like for you.

Jolene McIlwain: Thank you so much, Meredith. It’s been surreal. I’d always wanted to publish a book, but now that it’s happening, I’ve realized that this project has always been about much more than writing stories for a collection. Sidle Creek is a tangible record of my attempts to make sense of the challenges my friends and I faced in the years I composed the stories. We’d spent the last decade raising kids while caregiving for ailing parents and grandparents. We’d nursed elder-dogs and elder-cats, all the while dealing with medical and mental health issues and chronic illnesses of our own. We’d worked two jobs at a time, or more. We’d buried friends and family members. Writing my stories helped me get closer to answering some difficult questions: How do any of us find help and give care? How do we deal with estrangement? How do we connect? How do we heal? How do we navigate grief, illness, trauma? And most importantly, how do we become more resilient and thrive? I feel strongly that “nature heals” is more than a slogan. In these stories, I explored my conviction that hope is possible, even certain, when we, in desperate times, open our eyes more broadly to the natural world and what it has to offer.

MM: Of your many strengths as a writer is your ability to evoke a sense of place. In the collection’s title story, which also happens to be the lead story in the collection, you orient us to the world you are about to create—not just the external, physical geography of Sidle Creek, but its internal, psychological geography; its importance to virtually all of the characters in the stories is the thread that runs throughout the entire collection. Can you tell us how that came to be?

JM: The fictional world of Sidle Creek is very similar to my hometown. The characters are from a place that’s working so hard to deal with the mistakes of the past, make plans for the future, and manage the present struggles. I wanted my stories to offer a window into how people react—especially those living in economically depressed rural small towns—when institutions and agencies of the medical, religious, educational, child protection, environmental protection, and criminal justice fields, fail to help them in ways they most need. So, some characters rely on superstitions and clairvoyance. Some rely on an underground economy or justice system. Some characters rise to the occasion, rallying, helping those in need, and some escape into fantasies of flight or actually run away when their problems are too large to bear.

The psychological geography also includes issues I deal with as I straddle the worlds of rural working-class and academic, artist, and white-collar corporate cultures. There’s an internalized classism that makes it difficult to feel great pride about where you come from, especially when stereotypes and caricatures of the people and place you were born dog you. People have so many preconceived notions about Appalachia that are misguided and limiting.

The poet/author, Idra Novey, in her interview with Maris Kreizman of The Maris Review podcast, says “I think so much of the literature about Appalachia and the discussion around Appalachia feels like an obituary. I didn’t want to add to that. Appalachia is beautifully, complexly alive, and I wanted to figure out a way to write about it that felt like I was writing and imagining its future and imagining a present that is vibrantly alive.”

I could not agree more.

MM: Which was the first story you wrote about Sidle Creek? Did you always plan to keep revisiting it? Or did you finish one story and feel as if you weren’t really finished plumbing its depths?

JM: I’ve always been fascinated by creeks. If you’re a creek lover like me, you know that creeks are certainly characters, much like people. They are reactionary, bold. They find their best paths, sometimes changing paths, midstream. They get lost. Begin again. Some flow with a loud rush, some run so quietly they could easily go unnoticed. While I didn’t intend on writing about creeks or the environmental crisis we are faced with, I did want to capture how we are like creeks, built by and reliant on our surroundings—environments that can be empowering and healthy or toxic and debilitating.

The oldest story of this collection, “Seed to Full,” is one that I excerpted from a project I began writing over a decade ago—a still unpublished novel titled Jumping Traces—that featured two creeks, the Sidle and the Spare, one thriving and healthy, one shallow and polluted. In my short story, however, there’s only the Sidle creek, where a woman goes to reflect on her pregnancy, then later, her tragedy. The next few stories I wrote after “Seed to Full,” offered bodies of water much more integral to the plots. In the title story, “Sidle Creek,” a young woman believes the creek might magically heal her. In “Loosed,” a man relies on the water to bring clients to his hidden blood sport business. In “Shell,” a marsh near the Sidle creek offers all a couple needs to predict the future.

MM: You write short fiction, flash fiction and novels. Once you have an idea for a piece, does it immediately suggest its form to you, or do you have to wrestle with it for a while? Do you ever get all the way to the end of a draft and then decide it should be something else?

JM: “Drumming,” one of the shortest stories in Sidle Creek, had its beginning in a much longer story I’d been frustrated with and had given up on years ago, titled “Unlocked in the Cabin.” The main character, taxidermist Rudy Greeley, dined every morning at the same spot. A waitress at that diner, Dusty Sinclair, and her friend Elbert, were in the story simply as part of the world-building for Rudy’s life. I’d introduced them in one line of backstory. Years later, in a flash fiction class by Kathy Fish, we were asked to pick one or two characters from an abandoned story and take a closer look at their personalities, what haunts them or plagues them. I pulled Elbert and Dusty from “Unlocked in the Cabin,” and explored a scene where they’re talking about fracking and infertility, and I immediately had “Drumming.”

A few of the stories in Sidle Creek were from chapters in two longer projects. “Oiling the Gun” and “Seed to Full.” But “The Less Said” is a story that started as a flash, and it kept growing until it became a mosaic of sorts with a dozen sections and several narrators. Even after I’d submitted the collection, my editor at Melville House asked me to add more to it. It began as the tale of one man who finds an odd pulley strung up in a tree at a rundown campsite while out foraging for mushrooms. He raised suspicions with his neighbors that something criminal might be happening at this spot. After I wrote his section, I couldn’t stop thinking about how others, stumbling upon that same campsite, might have their own ideas about what happened there. Some narrators would know the truth because they’d witnessed events there unfolding. The story grew as stories in small towns grow—layer upon layer of rumor.

MM: What is that process like for you? Are you a morning writer? Or a night owl? Do you ever work simultaneously on stories and novels—or do you tend work in a more linear way?

JM: I work on several projects at at time. It’s not efficient but it’s so intriguing to see how each project informs the others in some way.

I am a morning writer—the sweet spot for me is between 5:30 and 7:30 am—but I’ve had to learn to become an “anytime-I-find-time-to-write-writer.” I’ve drafted and revised while running errands for my husband’s excavating business, waiting in doctor’s offices, waiting for my son to get off the bus, waiting in traffic on route 28 where I’ve voice-recorded parts of stories on my phone while commuting the 35 miles back and forth to my teaching jobs in Pittsburgh. This is likely why several scenes are inspired by my favorite music I’d play while driving. In fact, I have a Spotify playlist I created from the songs I worked with for both generating scenes and revising them. “Sostenuto” was inspired by Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9. Luke Abraham’s character in “Loosed” was inspired by both Johnny Cash’s rendition of “Hurt” and Nirvana’s “The Man Who Sold the World.” “Eminent Domain” was inspired by 4 Non Blondes’s “What’s Up?” A scene in “You Four Are the One” was inspired by James Taylor’s “Handyman.”

Most of my stories begin with sounds, images. My current novel project began with sound recordings I’d made at spots along the Allegheny River. I’d drive to a dock or a trail along the river and record for just a few minutes. After I recorded snippets for about six months, I began writing the scenes of the novel.

MM: Many of your stories deal with loss, grief, and trauma—and your viewpoints are varied, men, women, and children. As a developmental psychologist, I found your portrayals of grief and trauma to be not only raw and powerful but also extremely authentic. How did you get it right? What was the biggest challenge in writing those particular stories?

JM: Thanks so much for saying this. That means so much to me. The biggest challenge for me was in keeping myself from veering into melodrama or sentimentality. My stories are often dark, heavy, but in many ways, they mimic the kinds of trauma and violence I’ve seen unfold in places I’ve worked and visited, particularly hospitals, both as an X-ray technologist/caregiver and patient. Of course, the violent acts—re-breaking an arm, having a person hold still for several minutes for a needle-directed breast biopsy, or myelogram, or a baby’s complicated delivery—are committed solely for a greater good. However, a part of the mind experiences these actions inaccurately as assaults; it can’t distinguish between acts meant to harm or heal.

I’ve seen people in their most vulnerable and pained moments in hospitals, and I’ve been completely in awe of the grace they’ve sometimes shown in the midst of traumatic or tragic moments. So, I’ve certainly pulled from both my work as an x-ray tech and a caregiver and used those events as inspiration for writing scenes in which my characters, I hope, show some form of grace or reckoning in their moments of physical pain as well as mental pain that’s been triggered by regret, failure, or fear.

MM: Who are your literary idols? Which writers living or dead have influenced you the most?

JM: The poet Jane Kenyon is probably my greatest literary idol. But my earliest influence was E.B. White—Charlotte’s Web remains one of my favorite stories. In college, my teachers introduced me to works with a level of artistic genius that illustrated what was possible with language, form, place, and genre. Those authors are Toni Morrison, William Faulkner, Annie Proulx, Dorothy Allison, Sandra Cisneros, Louise Erdrich, Breece D’J Pancake, Jeannette Winterson, Kent Haruf, and Angela Carter.

I am simply blown away by the writers who’ve been publishing in the last decade or so—how they’ve blended genres, upended tropes, pushed the boundaries of what a narrative can look like, but I’ll stop at my earliest influences because this list is far too long…

MM: There is quite a bit of detail about hunting and dog fighting, about herbal remedies, fishing, logging, and woodworking. You write with great detail and authority about all these topics. How did you go about doing the research for those stories?

JM: For research I’ve always tried to get straight to the actual experts when possible. I was raised by anglers and hunters, so that comes easily. My husband’s family farms and his brother has a portable sawmill. I’ve asked so many questions of the Amish contractor we’ve employed for renovations. You Tube interviews have been an immeasurable resource. For example, for the story “Loosed,” I watched interviews with MMA fighters and parents whose children competed in that sport. I also tried to find deeply investigated, objective news stories and read dozens of articles outlining the searches on Michael Vick’s land as well as news stories on underground fight clubs.

A lot of Sidle Creek is inspired by childhood memories, so I’ve regularly texted or called my mom asking her questions like, “Who was that guy Dad knew who did ammo reloads in his basement workshop?” I love to do investigative road trips, and conversations around my neighbor’s campfires sometimes seem to lead to ghost stories and questions like, “If you had to hide a body, where might you hide it?”

MM: Can you give us a hint as to what you are working on next? (Because I, for one, can’t wait!)

JM: Yes, I’ve been working on two novels. They both take place in the same fictional world as Sidle Creek. One is set in a farming community, and one is set in a river rat community. Both revolve around murders and neighbors and the harsh realities of small-town complicity. I’m also working on a nonfiction hybrid project I’ll be workshopping this summer at VCFA’s post graduate conference with the amazing Nick Flynn. It’s about the men in my life and my love of water.

That all sounds amazing, Jolene! Thanks so much for talking with me. I look forward to celebrating the launch of Sidle Creek—and to continuing our conversation—on May 16th at 7:00 pm at The Penguin Book Shop, 417 Beaver Street in Sewickley.

Hope to see you there, Littsburgh readers!

Meredith Mileti is the author of Aftertaste: A Novel in Five Courses, published by Kensington Books. She resides in Pittsburgh, where she is an active participant in the arts and literary community. Meredith has been the recipient of artistic fellowships at The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts in Amherst, Virginia, and the VCCA Le Moulin à Nef residency in Auvillar, France. She is currently at work on another novel.

Start Reading Aftertaste: A Novel In Five Courses by Meredith Mileti…