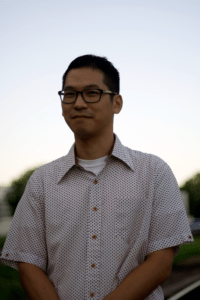

Robert Yune is one of the nicest and most thoughtful authors out there — and he’s been such a big supporter of Pittsburgh’s literary scene and of Littsburgh — that we couldn’t wait to interview him about his new book, Impossible Children (out now from Sarabande Books!). If you have any interest in literary Pittsburgh, you’ll want to read to the end of this Q & A (which covers Chuck Kinder memories, the jazzy improvisation of Rialto’s red lights, and writing about Western PA).

And if you’re anything like us, Yune’s answers are going to make you want to add his new book to the top of your list!

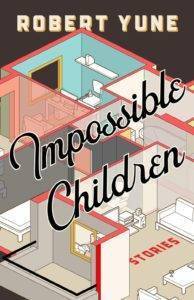

From the Publisher: “In these inventive short stories, characters must navigate an impossible world: America as we know it. Two estranged brothers on a road trip attempt to reconcile but end up at a Revolutionary War reenactment camp; a young woman moves in with her boyfriend and discovers an eerily personalized seduction manual on his bookshelf; a middle-aged Korean-American father attends college courses and is either blessed or haunted by the presence of Edward Moon, an eccentric billionaire who also happens to be ‘the most successful Korean in America.’

Playfully engaging with genres like science fiction, the fairy tale, and the Gothic tale, the interconnected short stories of Impossible Children (winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction) pit tiny heroes against tiny villains; the result is a stunning mapping of geography, heritage, immigration, freedom, and the mysterious forces behind epic ruins and epic successes…”

About the Author: Robert Yune’s fiction has appeared in Green Mountains Review, Kenyon Review, and Los Angeles Review, among other places. His novel Eighty Days of Sunlight was nominated for the 2017 International DUBLIN Literary Award. Currently, he teaches at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, PA.

“Robert Yune’s magnificent and richly assured debut, Impossible Children, takes us across the United States, from New Jersey to Michigan to Alaska, portraying the lives of the itinerant, the wanderers, and the lost. Like Stuart Dybek’s Coasts of Chicago or Edward P. Jones’s Lost in the City, the stories―through a fully realized community―embody and evoke generations, history, and the history of war and migration. Many of the stories focus on the experience of Korean Americans, though one of the many striking aspects of this book is that it never stays within the borders of a single culture or community, but rather continuously expands across landscapes that are at once familiar and yet difficult to categorize in simple terms. This is a collection that is both precise―in language, in imagery and tone, revealing key moments in a life―and vast in geography, events, and the heart.” ―Paul Yoon, judge, April 2017

“As hard as Robert Yune’s characters try to escape their Korean heritage and disappear into a rootless America, they can’t run from blood. As one laments, ‘Sooner or later, everything returns,’ yet there seems no way to reassemble the once-missing pieces and become whole again. With a clear-eyed grace, Impossible Children chronicles a generation struggling to bear the weight of their inheritance.” ―Stewart O’Nan, author of Henry, Himself

“The characters at the heart of Robert Yune’s vibrant debut story collection, Impossible Children, are treated with such warmth, such sincerity, that the reader is genuinely engrossed by every twist and turn of their extraordinary lives―though especially by their dreams of America, both ones that come true and those they heartrendingly abandon. Written in voices that show a breadth of immigrant experience, this collection brings alive the all power and magic of the short story.” ―Jeffrey Condran, author of Prague Summer

“Elegant, absurd and unexpected, the stories in Robert Yune’s debut collection bring to mind the fictional worlds of Gary Shteyngart and Chang-rae Lee. Through these seventeen stories of misfits and lost souls searching for connection within their own families and the world, Yune creates a poignant and complex portrait of contemporary America. The stories capture the restlessness of characters set adrift by circumstance, by their own impulses, by the impossible demands they make on themselves and others. Yune is gifted at capturing the contradictions, imperfections and pleasures of family and home.” ―Geeta Kothari, author of I Brake for Moose and Other Stories

In your last novel, Eighty Days of Sunlight, Pittsburgh was almost a character. You wrote that one while you were living in the city—and then you moved. Are folks in Pittsburgh going to recognize any settings in Impossible Children, or did your settings move with you?

In your last novel, Eighty Days of Sunlight, Pittsburgh was almost a character. You wrote that one while you were living in the city—and then you moved. Are folks in Pittsburgh going to recognize any settings in Impossible Children, or did your settings move with you?

When I’m in town, I say that sixty percent of my novel—the best sixty percent—takes place in Pittsburgh. I wrote eleven of Impossible Children’s short stories while living in Pittsburgh and two while I was living in Gettysburg, so a whopping 76% of the collection is certifiably “made in Pennsylvania.”

Anyone from Western PA will recognize the rhythm, landscape, and characters in “Click,” which is one of the most personal stories in the collection. It’s set near Butler. “Click” is about a police officer who catches a man transporting a dead deer in the cab of his pickup truck. Naturally, the cop has questions, but the driver isn’t terribly interested in answering them. This was the first story I wrote after moving from Pittsburgh to Indiana—I was missing my friends and the Burgh, and this story just kind of emerged. I guess I subconsciously associate Western PA with ornery characters.

At Pitt, I taught this OSHER class, which is for students 55 and older. It was a literature class called “Reading Pittsburgh” and featured works by Pittsburgh writers—or writing about the city. Teaching this class was a particularly bad idea. I mean, my students were great, but some days, I got schooled because they knew way more about city’s neighborhoods than I did. Some of them actually worked in the steel mills, or could remember Shadyside before gentrification (it was apparently the sex work capital of the city). That class was a great learning experience, especially since my friends are mostly young and mostly didn’t grow up in the Burgh.

At Pitt, I taught this OSHER class, which is for students 55 and older. It was a literature class called “Reading Pittsburgh” and featured works by Pittsburgh writers—or writing about the city. Teaching this class was a particularly bad idea. I mean, my students were great, but some days, I got schooled because they knew way more about city’s neighborhoods than I did. Some of them actually worked in the steel mills, or could remember Shadyside before gentrification (it was apparently the sex work capital of the city). That class was a great learning experience, especially since my friends are mostly young and mostly didn’t grow up in the Burgh.

In Impossible Children, the most recognizable Yinzer element is probably the emotional landscape. Reverence isn’t exactly a natural emotional state for Pittsburgh residents… this probably has something to do with the region’s labor history. And throughout my book, you can see my characters struggling against oppression and authority by using familiar and unconventional tactics.

Can you tell us how living in Pittsburgh influenced some of your stories?

The boring answer is that I wrote many of these stories while earning my MFA from Pitt. I started writing this collection in 2005, and I shared a number of its stories at public readings around town. Just like a stand-up comic trying out new material, I often revised these stories based on the crowd’s reaction. So, in a lot of ways, Pittsburgh was my test market.

I wrote Impossible Children while living in Bloomfield, Squirrel Hill, and Trafford. While all those neighborhoods certainly have character, none of them are particularly weird. I finished and edited Impossible Children in Troy Hill and Forest Hills, which are both pretty weird. Living in Western PA, you develop a jazzy, improvisational mindset because when the traffic light at the bottom of Rialto Street gets stuck on red, no one’s going anywhere. Also, taking a detour through Forest Hills means you end up driving on roads so steep it’s hard to believe you’re in North America. It feels like you’re diving through that folded-up city in the movie Inception.

I have a love-hate relationship with Pittsburgh’s landscape, which can be isolating and frustrating. At the same time, because it’s so geographically and culturally fractured, the city has managed to preserve its local cultures and identities. In contrast, most American cities are bland, sanded-down copies of each other.

Impossible Children is a big collection with a variety of stories. There’s a futuristic, sci-fi-inspired piece. There’s a modern fairy tale. There’s a dark psychological thriller. When I was revising it, I said to myself, “Well, if Pittsburgh can stay weird while maintaining its identity, then this book can, too.” I mean, Lawrenceville turned a funeral home into a gastropub. The city’s best Thai restaurant is in Bloomfield, Pittsburgh’s “Little Italy.” The Original Hot Dog Shop remains wild and ungentrified. It all makes sense somehow, and I’d like to think my story collection does, too. There is a unifying logic that makes sense once you’re in the thick of it.

You were really involved in Pittsburgh’s literary community when you were living in the city and I’m curious if you miss it, or if you’ve found something similar in Gettysburg?

I absolutely miss it. Living elsewhere gave me a useful sense of contrast. I hadn’t fully realized how dependent I was on Pittsburgh’s literary community for emotional support. Don’t get me wrong: there were lovely events in Gettysburg, but it’s rare and wonderful that Pittsburgh has so many reading series and resources. It’s especially heartening that so many literary organizations are connecting with community nonprofits to raise money and awareness.

Shout-outs to Girls Write Pittsburgh, The Bridge Series, and City of Asylum. And for what it’s worth, I wish every city had its own Littsburgh.

Your publisher has called Impossible Children a book about “navigating an impossible world: America as we know it.” Did you set out to write a book about America or did the stories lead you there?

I’m a first-generation immigrant. My parents adopted me while my dad, who was an officer in the US Navy, was stationed overseas. My earliest memory is playing in a sandbox in Italy. Growing up, my parents would tell these wonderful stories about their adventures abroad, and so, from a young age, I developed a fairly unique sense of America by comparing it to other countries we’d lived in. I also had a good sense of what my life would have been like if I’d stayed in South Korea. (Given the state of the country at the time, I’d probably be gutting fish on a fume-soaked dock.)

I didn’t specifically set out to write a book about America, but I’ve spent the past decade worrying and wondering about this country, and a number of subconscious issues naturally surfaced in my writing. Also, living in the Midwest reminded me how huge and strange this country is. I think that was a new useful contrast for me. Moving from Pittsburgh to Indiana was such a culture shock—and then Trump became president. The whole experience forced me to pay attention and listen to people I otherwise would have ignored. Everyone knows this country is full of people who see the world differently and have different values, but being immersed in that difference was eye-opening.

I remember seeing your Chuck Kinder tribute post on Facebook recently. As a former student, I wonder if you could share your favorite memory or anecdote.

In college, our fiction workshops were held on the fifth floor of the Cathedral of Learning. We all crowded in this tiny classroom around a circular wooden table. Chuck was a big guy, a towering literary presence wearing a red flannel shirt and jeans. Everyone knew about his reputation as a muse and an “outlaw writer,” but on the first day of class, when he lumbered into the room with his mustache, ponytail, and smoky-lens spectacles, no one knew what to expect.

I didn’t really notice the man’s outlaw tendencies until one day when a student accidentally took his seat and Chuck insisted on sitting so he was facing the door. I realized he’d been doing that all semester. In that moment, I felt the same buzz of energy everyone had on the first day of class. It seemed completely possible that at any moment, someone might burst through that door while Chuck was teaching and challenge him to a duel.

I’ve heard writers lament about the “good old days” of creative writing instruction, back when professors would show up drunk and you could smoke in the classroom. I’m old enough to have experienced that old-school style of teaching creative writing, and the truth is, it mostly sucked. Precious few people actually knew what they were doing. Chuck was rare because he was a great teacher. He looked like someone who distilled moonshine in a cave, but he quoted Aristotle and Chekhov just as often as he quoted Hank Williams or Patsy Cline. He had a hard-earned understanding of where good writing comes from.

One day in Senior Seminar, he brought in a chapter from his book manuscript. The pages were practically dripping with red ink. “Here’s what my editor thinks about my writing,” he announced to the class. He’d copied the chapter for all of us and said it was optional reading. “Since I’m giving all of you feedback, I figured I might as well share what the process is like for me.” He was willing to be fair—and even vulnerable—in the classroom, and because his students trusted him, he could challenge us in numerous ways.

I could share any number of stories about Chuck, but I’ll end with this one. It’s about West Virginia. Before I studied with Chuck, I’d only driven through the state at night: I remember these impressively tall white crosses erected by the roadside and lit up by floodlights. There were dozens of them, spread out through the state. They’d just appear in the middle of nowhere, like an omen or a warning. The only radio stations played country music and preachers reading slowly from the Old Testament. The trees by the roadside seemed especially hairy and menacing. I remember driving as fast as I could over those windy country roads, and I didn’t feel safe until I’d passed Morgantown.

A couple weeks ago, I drove through West Virginia again. I saw a sign for a “Palace of Gold” and followed it deep into the heart of the state, for nearly an hour over some surprisingly steep hills.

For some reason, there’s a sizeable Hare Krishna settlement in West Virginia. Their temple is high above the Ohio Valley, with a clear view of the Appalachian Mountains. Upon reaching it, I parked and stepped out of my car, but there was a wall around the temple itself. I followed it and found myself on a trail through the forest that led downhill, past a gauntlet of semi-tame peacocks. I knew I was getting farther from the temple itself, and as I passed a lake and a massive elephant statue, the building was completely out of sight. I wandered through dormitory-style housing, complete with a laundry room. There was a circle of folding chairs in one front lawn, but I didn’t see any people.

I thought of Chuck—partly because he’s a hippie from West Virginia and probably knew everyone in the compound—but also because he would have approved of me venturing off the map into unknown territory. In the end, good writing isn’t just about skill—it’s about being open and curious and eager to explore why, say, a group of Hindus would dedicate their lives to building a gold palace in a state best known for its coal mines and moonshine. For what it’s worth, once I found people, they were warm and welcomed me into their home, even though I was a lost tourist who was clearly trespassing at a strange hour. That warmth reminds me of Chuck as well.

Robert Yune’s new book, Impossible Children, is out now from Sarabande Books.