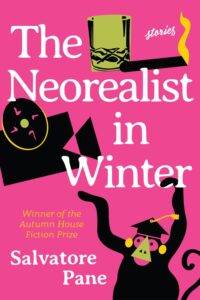

From the Publisher: “Salvatore Pane’s The Neorealist in Winter is a collection of eleven short stories that explore what it means to be human in an age of media oversaturation. Utilizing methods of speculative, historical, and postmodern storytelling, Pane grapples with legacies of immigration, poverty, toxic masculinity, and moral failures, while focusing on working-class issues, family drama, and PTSD. Following eleven Italian narrators, Pane builds a cast of cinematic characters across disparate times and places—a struggling director attends a house party in the la dolce vita of 1960s Rome, gangsters chase a low-level lottery runner in coal valley Scranton, a woman contemplates experimental surgery to purge memories of her childhood trauma in Minnesota, and a pro wrestling promoter descends into self-denial through his autobiography.”

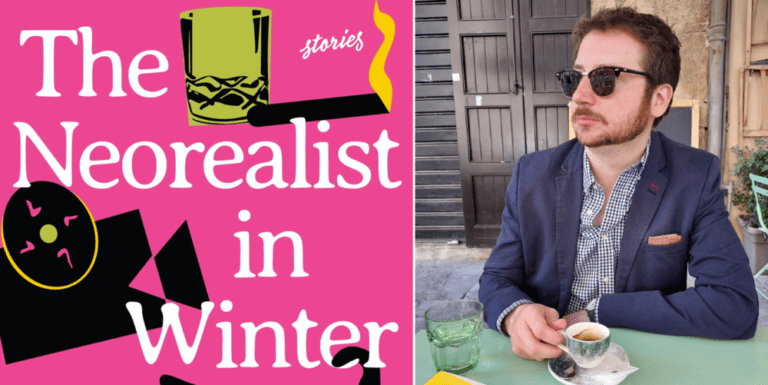

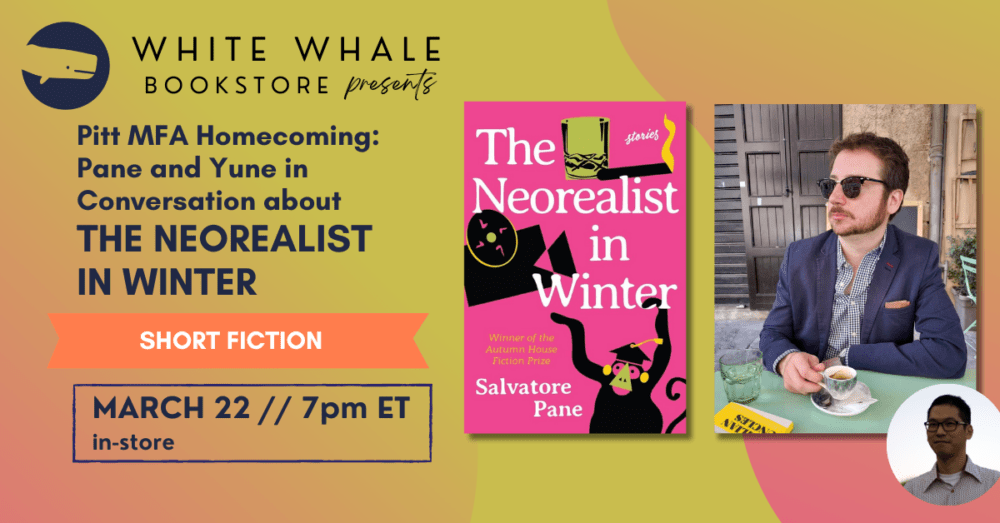

Read an Excerpt! About Salvatore Pane: Salvatore Pane was born and raised in Scranton, Pennsylvania. His short story collection, The Neorealist in Winter, won the 2022 Autumn House Fiction Prize and was published in October 2023. He is also the author of two novels, Last Call in the City of Bridges and The Theory of Almost Everything, and a book of nonfiction, Mega Man 3. He’s also written video games and graphic novels, and his textbook, Story Mode: Writing Narrative Video Games for Everyone, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury. He holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Pittsburgh and currently serves as an associate professor at the University of St. Thomas. He lives with his wife and Martin Scorsese the Cat in St. Paul, Minnesota.

More Info About Avery Bauer: Avery Bauer is a fiction writer currently in her final year of undergrad at the University of Pittsburgh, majoring in English Writing. She has previously received third prize for The Taube Fiction Award in 2023. Her work appears in urban cowgirl renaissance and is forthcoming in Collision.

Event Info Don’t miss out: Salvatore Pane will be in conversation with Robert Yune at White Whale on March 22nd!

How would you describe this book?

How would you describe this book?

The Neorealist in Winter is a book about generational trauma and PTSD and interrogating what, if anything, it means to be an Italian American in the 21st century. It’s an attempt to wrestle with our potentially toxic relationship to media and the ways in which we shield ourselves from the larger problems of the world and our flawed human hearts.

You’ve written in a few different genres and styles, including nonfiction novels and video games. How would you describe your relationship with and understanding of short fiction?

Writing short fiction is like returning to an old friend. It’s the form I spent the most time with as a student during years and years of workshop, so I view the short story as a genre I can recharge in whenever I get stuck inside of a larger work like a novel or a book of nonfiction. But short stories aren’t side projects for me. Some of my favorite writers are primarily short story writers (Raymond Carver, Danielle Evans), and I always read lit journals and Best American Short Stories every year. Coming up, I never wanted to publish a random collection of short stories. I wanted to wait until I had a series of stories that were cohesive and thematically linked, and I hope that Neorealist does that.

This collection has a lot of references to film, television, and the internet, and a few stories in which this media is a significant portion of a character’s life. Why did you decide to explore people’s relationships with media?

Our relationship with media is one of my central preoccupations. I was born in the ‘80s, a few years after Reagan deregulated advertising to children, and this directly led to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Transformers and G.I. Joe, and all these other properties people my age grew up loving and still adore to this day. But all those shiny cartoons were primarily conceived as infomercials for plastic action figures, and I think that warped our relationship to pop culture in a significant way–especially when you compare the way millennials and gen z treat pop culture vs. gen x and the boomers. So much of my life and the lives of my friends have been spent dissecting this minutia, and I’m interested in what those obsessions say about us. Is this a productive way for me to engage my inner child, or am I using movies and TV and video games to avoid the world? I still don’t know the answer, so I like to run my characters head first into that question.

How has your own relationship with media affected your own writing?

It’s affected my writing dramatically. I’m a cultural omnivore. I try to devour everything, and I think this shows up constantly in my writing. I’ll write a book about video games, and then I’ll write a video game, and then I’ll play a video game, and then watching GoodFellas will lead me into a story, and it all feels like an ouroboros. It’s how I refill the creative well.

The main characters in these stories all have some awareness/connection to their Italian heritage. How would you describe the way this factor into their stories?

I grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania, which was very much an Italian American enclave. But I didn’t realize this as a kid. It all just felt normal, and it wasn’t until I moved for college and then later to Pittsburgh when I realized Scranton was a pretty particular place. The characters, then, are wrestling with their own murky sense of identity. What does it mean to be Italian American today? Does it mean anything? Or is it just a hokey connection to a completely fabricated European past that has no basis in reality? Is it just that we eat a lot of pasta and watch The Sopranos? But how much of our behavior is just a stereotypical reflection from Mean Streets or Godfather? So many Italian Americans talk about Italy like it’s this fabled homeland, but whenever I go there and ask European Italians what they think of their American cousins, they respond like that Don Draper Mad Men meme where he says he doesn’t think about us at all. I have no idea what to make of my background, so the characters struggle with that question too—especially when it’s complicated by their poor relationships with their families.

What about Italian and Italian American culture/heritage/people made you feel compelled to represent them in these stories?

I thought a lot about Philip Roth and that for so many he was the chronicler of Jewish identity in America for the second half of the 20th century. There are a lot of terrific immigrant writers who wrote about the experience of being Italian in America at the dawn of the 20th century—Pietro Di Donato and Pascal D’Angelo come immediately to mind. And there were a lot of incredible writers chronicling the Italian experience abroad—Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, and more recently Elena Ferrante and Francesca Marciano. But I don’t see a lot of mainstream writers—except for Christopher Castellani and maybe a few others—trying to tackle what if anything it means to be Italian American in the 21st century. I was fascinated by that idea, and more and more Italian American folklore started seeping itself into my work.

Many of these stories take place in or have a connection to places around Pennsylvania. Are there reasons, other than your familiarity with the area, that you chose these locations?

Charles Baxter once said that he only started writing about where he grew up after he left. He said that’s where his imagination lived, and I feel the same way about Pennsylvania. I spent my childhood in an old mining boom town, and the forest behind my parents’ house was lined with spoil tips of coal residue. Scranton is a valley swaddled by mountains and crisscrossed by train tracks. The bars I went to with my grandfather were full of people cracking peanut shells on the wooden floorboards beneath their boots. It’s so imprinted in my consciousness that whenever I write something set somewhere else it always feels like a juxtaposition to Scranton, and that isolation and longing always becomes part of my fiction. I long for my idea of home, but I’m fully aware that the Scranton of my imagination doesn’t exist. It’s changed as much as I have, and I use that gap to power my fiction.

A lot of the main characters seem to have complex interior lives and problems that those around them don’t seem to be privy to. Why do you think exploring internal thoughts and struggles is so important?

People, in my experience, are all carrying these internal burdens around that they only show to a privileged few. For me, that’s where the conflict of a short story lives—the tug of war between one character’s hidden struggles or baggage and then the demands of the wider world or even the equally hidden lives of other characters. I’ve been in therapy for five years, and I spent so much of my life trying to conceal all the messy parts of myself that I thought no one would be willing to acknowledge, let alone accept. So, to me, it unfortunately seems very normal to try and just suffer through without reaching out for help. Obviously, that’s a bankrupt way to live, and I think that’s why so many of these characters stumble into extreme moments of crisis.

What do you hope readers take away from these stories?

I hope that readers can revel in something that isn’t pure escapism. I want to linger in the difficult moments, because I feel like so much of art and media in general is geared toward making us forget our problems so we can be sold something. Obviously, I’m selling you something too—a book—but I hope Neorealist can be frank about depression and generational trauma and not saccharine for the sake of a bottom line. Whenever I read anything, I’m hoping to have my heart cracked open and reassembled. My sincerest hope is that Neorealist does that.