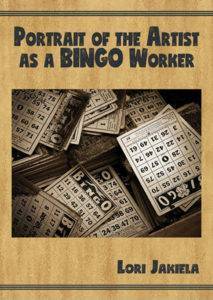

“If you grew up in working-class Pittsburgh in the 1970s and 1980s, you knew books were dangerous,” Lori Jakiela — author of Belief Is Its Own Kind of Truth, Maybe — writes in her latest book, Portrait of the Artist as a Bingo Worker (Bottom Dog Press, August 2017).

“Books gave you ideas,” Jakiela writes. “Books hurt your eyes.”

A celebration of work and books and ideas will mark the publication of Portrait, Jakiela’s fourth memoir, beginning at 7 p.m. Friday, Sept. 29 at Abandoned Pittsburgh (203 East Ninth, Homestead, PA), a gallery run by artist and photographer Chuck Beard, whose image of bingo cards highlights the cover of Portrait.From the publisher: “Adopted into a working-class family in Trafford, Pennsylvania — a mill town built by George Westinghouse–Lori Jakiela has been a bingo worker, a waitress, a journalist, a sportswriter, a temp worker, a Things Remembered key maker, a flight attendant, and more. She now teaches creative writing at a university. Portrait of the Artist as a Bingo Worker maps Jakiela’s journeys through bad jobs, good jobs, and everything in between as she tries to find herself as a writer. In Jakiela’s working-class world, only rich people were allowed to dream of being artists and writers.”

I worked bingo nights at the Trafford Polish Club on Mondays and Wednesdays. I was 17 and worked for my grandmother Ethel, who ran the kitchen. Ethel was 230 bad-tempered polka-loving pounds in a housedress and slippers.

I worked bingo nights at the Trafford Polish Club on Mondays and Wednesdays. I was 17 and worked for my grandmother Ethel, who ran the kitchen. Ethel was 230 bad-tempered polka-loving pounds in a housedress and slippers.

“I don’t need to impress anybody,” Ethel said. “I don’t gussy up.”

Ethel shouted misery and joy, nothing in between. I’d been working for her since I was 12. None of Ethel’s seven other grandchildren would even consider it, such was the abuse, but I prided myself on my endurance. I also liked the money for clothes and books and music.

At 17 I was partial to black velvet culottes and fedoras I’d find at Goodwill. I’d just discovered poetry, classics like Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson and e. e. Cummings. I spent a lot of money on hardbacks at Walden Books in Monroeville Mall, where I also found Rod McKuen, a 1970s sap poet and songwriter whose critically-bashed books like Listen to the Warm and Caught in the Quiet matched my angsty teenage heart.

I liked McKuen because he translated Jacque Brel’s “Le Moribund” into “Seasons in the Sun,” a song about dying young I’d play on repeat, goodbye to you my trusted friend. I liked that McKuen looked sensitive in his sweaters and berets and that he was adopted, like me. He wrote a memoir called Finding My Father: One Man’s Search for Identity, a book critics didn’t hate too much and which I snagged from Walden’s discount bin and sneak-read in Ethel’s Polish Club kitchen.

“You’re going to ruin your eyes,” Ethel said when she caught me reading.

“Idle hands are devil’s playthings,” she’d say and hand me a bag of cheeseballs to fry.

Ethel paid me what she felt like paying, depending, but there were tips and everything was cash, wads of ones that, on a good night, made me feel stripper-rich. I could pocket bills, but a lot of the senior citizens at bingo tipped in change and Ethel made me put the coins in a jar she tallied every night. She called change-tips “found money.”

Found money, Ethel claimed, was lucky and meant to be shared. She traded it for instant bingo tickets, the kind where you pull the paper flaps back to see if they spell out “Bingo” or the message “Sorry You Are Not an Instant Winner.”

Ethel and I were supposed to split the tickets and winnings 50/50, though I don’t remember ever agreeing to that. I think, when Ethel hit, she kept it secret. I’d win a dollar here or there, but never enough to make back what was in the jar.

“You weren’t born lucky like me,” Ethel said more than once.

“We’re family,” Ethel said as she doled out my pay from her apron pocket. “And family is more important than money. Family is more important than anything. Remember that.”

And so I didn’t count my money until I got home, where I closed my bedroom door and spread it out on my bed and sorted it into piles and tried not to do the math when I knew my grandmother shorted me.

“Be grateful,” Ethel said. “You kids today are never satisfied.”

I wasn’t satisfied. Still, most days I worked hard despite it. I was raised to believe in work and family, and I wanted my grandmother to love me even though I was adopted and not family in the sense she meant when she invoked it.

“Your mother couldn’t have children of her own, so we got you,” Ethel said about my arrival into her family.

Ethel–old-school, first-generation American–believed in blood. I believed I could win her over anyway.

“Who is not a love seeker?” Rod McKuen said, but for adopted people like him and me, people who grew up believing in family as a dotted line, something that at any time could turn null and void and send us back to whatever lost place we’d come from, so much depended on being loveable, loved.

And so I tried to please my grandmother. I didn’t complain much. I tried to look pretty and pleasant. I hid my books under the prep table, and I was okay with the smell of grease and fish and with cleaning up whatever mess Ethel made. I tolerated Ethel’s habit of eyeing up my boobs to see if they were growing. I turned when she made me turn left, then right, then left so she could get a good look.

“You been letting boys play with those?” she said until I curled into myself like one of the ingrown toenails I’d clip from Ethel’s feet because she couldn’t bend down to reach them herself.

Safe sex, Ethel said, meant never letting a boy get on top of you. Safe sex, Ethel said, meant staying away from boys, period.

At 17, I didn’t have a steady boyfriend and the few dates I’d gone on weren’t promising. I somehow decided boys found it irresistible when girls went to sleep on them. I am not sure how I decided this–from Rod McKuen lyrics maybe, or romantic movies where the camera zooms in on a beautiful girl sleeping then cuts to a boy who looks on lovingly, tucks a blanket to her chin, and watches her all night long.

Whatever it was, I made a habit of resting my head onto boys’ shoulders and pretending to sleep. I learned I could pretend-sleep anywhere. I zonked out on boys at basketball games and school musicals and one Homecoming Dance and one Sadie Hawkins dance. I was shocked they didn’t call again.

I didn’t tell Ethel any of this because she seemed obsessed with talking about sex regardless, and had been like that long before I knew her. For years, my mother, Ethel’s daughter, thought girls got pregnant if boys’ tongues went into their mouths.

My mother grew up to become a nurse. My mother believed in science. When I asked how she ever bought the idea of spit-sperm, she said, “Your grandmother is not someone to argue with.”

“They’re only out for one thing,” Ethel said about boys.

Ethel said, “That’s how you happened, probably.”

I never knew Ethel’s husband, my grandfather. He died the year before my parents adopted me. He was an orphan, too. I’ve seen pictures–a tall thin man with dark eyes. He looked sad in his suspenders and fedora. His orphan story was different–his mother dropped him off at an orphanage when he was 10 because she couldn’t afford him anymore.

“No shame in that,” Ethel said.

Ethel had grown up poor, a child of the Depression. My grandfather had been born legitimate, with both a mother and father he knew. I was different.

There was no shame in being poor. The shame was sex.

“Some women don’t know how to keep their legs closed,” Ethel said.

In pictures, my grandfather looked plowed over by the world. I imagine all the years he spent with Ethel, that wall of sound.

“It’s a shame he died before you came,” Ethel said.

She said, “Maybe he would have known what to make of you.”

I wouldn’t read much into Ethel’s behavior toward me for a long time. I didn’t think about how adoption was probably a complicated problem for her. I didn’t wonder what was underneath her insistence that, if he’d lived, maybe my grandfather would have loved me.

Ethel was my only living grandparent. I had a lot invested in our relationship. I was used to the way she hit me with the wooden spoon she kept near the stove, the way she chased me around the Polish Club kitchen and pulled my long blonde hair. I figured we were close enough to be cruel to one another.

It’s easy, maybe, to mistake cruelty for honesty and to mistake honesty for love.

Sometimes I’d joke about getting Ethel a bikini. Sometimes I’d ask how many boys played with her boobs because they were big enough to rest a tray table on.

“Must be convenient on vacation,” I said about her boob tray.

This excerpt from Portrait of an Artist as a Bingo Worker by Lori Jakiela is published here courtesy of the author. It should not be reprinted without permission.