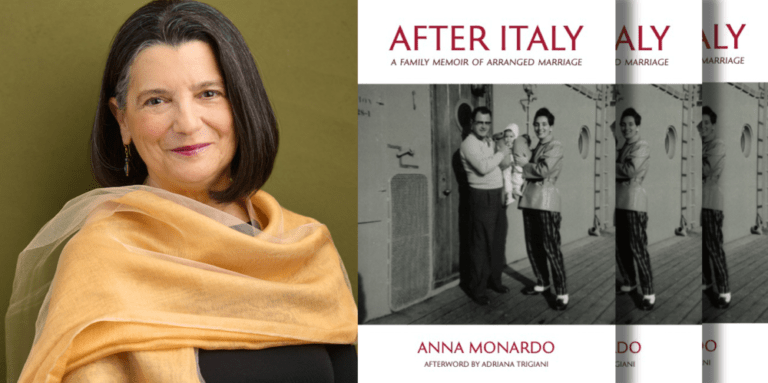

“Anna Monardo’s story is one of strength and vulnerability, the two chambers of the immigrant heart.” —Adriani Trigiani, The Good Left Undone and Big Stone Gap

From the Publisher: “Like her grandmother and mother, Anna marries quickly, knowing little about her groom. And like her maternal elders, she struggles in marriage. Determined to break the cycle of marital sadness, Anna sets out to investigate her family’s history, from their Calabrian mountain village and WWII survival, to their immigrant life in a Pittsburgh steel town, hoping to better understand the underlying forces that led to her own failure in marriage: Was it an Old World curse or a multi-generational trauma? What was gained and what was lost when the family’s Italian heritage intersected with American ideals? In time, she arrives at her own definition of domestic love by creating a path to the hopeful adoption of her son…”

More info About the Author: Anna Monardo grew up in Pittsburgh, with strong ties to her Calabrian family. Her first novel, The Courtyard of Dreams (Doubleday), set largely in Southern Italy, was translated into German, Norwegian, and Danish; featured in the Selected Shorts reading series at Symphony Space in New York City; and nominated for a PEN/Hemingway Award and recommended for the National Book Critics Circle Awards. Learn more about her at her website.

Author Site Don’t miss out: Anna Monardo will be in town for a Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures: Made Local event on May 23rd!

Event “This beautifully written story of three generations of marriage is a page-turner. Monardo’s honest and reflective memoir reveals intergenerational patterns as intricate as Italian lace. This family story has something to teach us all.” —Mary Pipher, A Life in Light and Reviving Ophelia

“As an Italian-American like Anna Monardo, I relished every detail of her family’s story from Italy to Pittsburgh. But you don’t have to share that heritage to love this exploration of love and marriage, family and motherhood. In After Italy, Monardo is a generous, wise guide into the past and into her own present. —Ann Hood, The Italian Wife and The Stolen Child

“In After Italy, Monardo crafts a moving, compelling, and gorgeously written memoir that is part cultural exploration and part emotional inventory. After Italy is a kind of translation, taking big questions involving society and self and relating them in the universal language of deeply explored personal experience.” —Sue William Silverman, Acetylene Torch Songs and How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences

“After Italy is an epic family history that spans generations, crosses oceans, and excavates layer upon layer of buried sorrows and secrets. It’s also a profoundly personal story told with intimate precision and in exquisite emotional detail. How did Anna Monardo pull off this magical double feat? By understanding that it’s all one big love story. Even when love is absent or imperfect or too lightly or tightly held, it’s always the main event. Monardo knows this intuitively and has written a beautiful and captivating book. I can’t wait to read it again.” —Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable: And Other Subjects Of Discussion

What made you decide it was time to tell the full story of your family’s experiences?

What made you decide it was time to tell the full story of your family’s experiences?

I recently found a note I wrote in my journal in 2008. My second novel, Falling In Love with Natassia, was published and I was figuring out what to focus on next: new fiction or a family memoir? I had notes for both projects, but about the memoir, I wrote this in my journal: “That memoir is the book I’ve been afraid of all my life.” When I found that note I knew I didn’t have a choice. I had to move toward what frightened me. I had written some of my family’s immigration story in my first semi-autobiographical novel, The Courtyard of Dreams, but now it was time to write the full story— the true story—about everything I’d fictionalized in Courtyard.

When my mother read Courtyard, she said, “You killed the mother.” And, in fact, the fictionalized mother does die “off-stage.” Within the plotline, her daughter and husband grieve for the mother, but the main conflict is the volatile relationship between daughter and father. With the mother “off-stage,” I didn’t have to write much about the parents’ marriage. In our family, there were aspects of my parents’ and grandparents’ relationships that were never discussed, and fiction allowed me to avoid digging in. As a daughter, I felt I was respecting my family’s privacy, but as a writer, I was being cowardly. Now, it was time for me to step up.

What kind of research and interviews did you do to gather information for your memoir?

After our father died, my brother and I found a trove of his Italian documents: birth certificate, passport, and even his elementary-school report cards—pagelle—which were little booklets. His 2nd- and 3rd-grade pagelle were made of heavy, cream-colored stock and the covers were embossed with the blue-and-red insignia for the Kingdom of Italy. The 4th-grade report card was made of a lesser stock, and it didn’t feel as good in my hands. The cover was red, with artwork depicting a rising block of interconnected towers—nationalistic. Fasces. No more Kingdom of Italy! The 4th-grade report card was issued by the Ministry of National Education, and printed on the cover in thick letters was Opera Nazionale Balilla, the Fascist Youth organization.

In my right hand I was holding the Kingdom of Italy report cards, and in my left, the Fascist-era card. I looked from one hand to the other, and realized that within the course of one summer break, from my dad’s 3rd grade to 4th, the dictatorship moved in. Less than ten years later, he was drafted into Mussolini’s army.

For my mother’s story, I filled a suitcase with her old photographs and went to Pittsburgh, where three of the cousins she’d grown up with went through the pictures with me, identifying people and places I didn’t recognize. We talked for hours. Two of the cousins were okay with the idea of my writing this memoir, but one cousin was not. “Your grandmother always told us you don’t go around talking about family stuff.” I was grateful for her honest reaction. It forced me to rigorously question myself about whether or not it was necessary to publish our story. Obviously, I decided to publish it, but I needed to examine that decision closely.

How does “After Italy” compare to your previous novels? How was the writing process different?

The novels and the memoir are similar in that they are all narratives built scene by scene. One difference is with dialogue—in memoir, the quotations are remembered; in fiction, they are created. For the memoir, the challenge was to craft dialogue that sounded like the specific voices of people I knew well. Writing fiction, I’m literally putting words into my characters’ mouths. Beyond that, writing the memoir was similar to writing fiction in that, with both, I’m trying to excavate whatever is going on in my heart. The challenge, when writing to explore emotion, is to make each character’s inner life accessible to the reader.

What kind of impact has your Italian-American heritage had on your life?

Though my Italian-American heritage isn’t my only heritage, it’s probably the most significant one. My Italian ancestry is so pervasive within me, I don’t even see it; it just is. But I was also shaped largely by the late 1960s and early 1970s, when I was an adolescent, just beginning to pay attention to the news and the world outside our home. Vietnam, MLK’s assassination, Kent State, Woodstock. The call for protest against injustice was powerful—and it was the opposite of the silent bella figura that a well-brought-up Italian American girl was supposed to emulate. The call for personal freedom was in the music, language, clothes, and I embraced that, too. It was thrilling. I was becoming an individual defined by forces beyond my family; and yet, the times assured me I was correct in doing so.

How has your life changed since the events of your book?

Having After Italy accepted for publication by Bordighera Press, which publishes literature and scholarship of the Italian diaspora, means a great deal to me. Writing this book, telling my family’s true story—the darkness and the light—was lonely at times, but with publication, so many beautiful connections have come about. Readers are prompted to tell me their own family stories, and it’s a privilege to hear them. Through Bordighera, I’m connecting with other Italian American writers and their amazing books. My father used to say, “Tutto il mondo `e paese.” All the world is one big village. I feel that now, more than ever.

Author photo credit: Chris Holtmeier Foton-Foto.