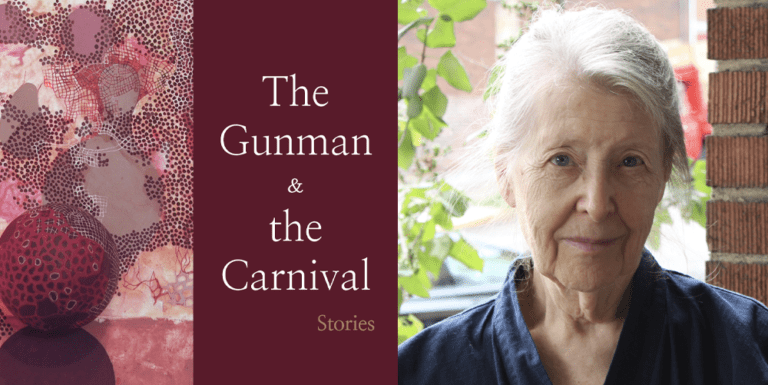

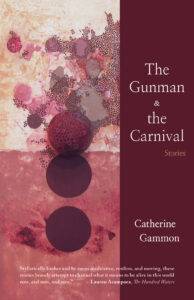

“Stylistically limber and by turns meditative, restless, and moving, these stories bravely attempt to channel what it means to be alive in this world now, and now, and now.”

-Lauren Acampora, The Hundred WatersFrom the Publisher: “Timely and introspective, Catherine Gammon’s The Gunman and the Carnival is the meeting of contemporary voices and visions that offer an intimate encounter open to strangeness and its embrace.

The stories in the inimitable Catherine Gammon’s The Gunman and the Carnival—loosely linked and set in Los Angeles, California—center on women of various ages and backgrounds. Constructed around themes of solitude and connection, creation and destruction, love, and loss, these sixteen stories unfold in a world haunted by individual and collective violence, systemic injustice, pandemic, and environmental duress: not with genre sensibilities of the dystopic or apocalyptic, but contained in the everyday reality of now. The Gunman and the Carnival does not aspire to be a panorama or to portray the city (or the nation) in its extraordinary complexity. Rather it shines a roving light into the minds and hearts of an idiosyncratic handful of characters living in our difficult times and invites each one to sing. Some of the stories are realist, some oblique and fragmented, others metafictional or surreal, and the urban/suburban landscapes are accented by the occasional appearance of wildlife and the presence (and voices) of trees. Handled with grace and intelligence, these stories chronicle contemporary struggles: the violence and the joy examined in equal measure…”

More info About the Author: Catherine Gammon is author of the novels The Martyrs, The Lovers (55 Fathoms, 2023), China Blue (Bridge Eight Press, 2021), Sorrow (Braddock Avenue Books, 2013) and Isabel Out of the Rain (Mercury House, 1991). Her early story collection is Beauty and the Beast (lulu.com, 2012). She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania with a garden and a cat.

Author Site “Catherine Gammon’s The Gunman and The Carnival is a collection full of strikingly familiar disappointments and betrayals woven through with an appreciation for moments of beauty amongst the daily degradations of contemporary life. Told with precision and honesty, these stories are richly nuanced explorations of desire, regret, hurt, and hard-earned acceptance.” -Jenny Irish, I Am Faithful and Lupine

“Gammon sharply observes her characters, loves them for their flaws and their hopes, and moves them through worlds defamiliarized by her punchy, powerful prose. Reading The Gunman and the Carnival made me revel in the joy and intensity of what a story can show us.” -Gwen E. Kirby, Shit Cassandra Saw

Why is it important to discuss the themes and conflicts in The Gunman and the Carnival, even as we live through many of them daily?

Why is it important to discuss the themes and conflicts in The Gunman and the Carnival, even as we live through many of them daily?

I don’t know that it’s important, but for myself, both as a writer and as a reader, I find the answer to this question in the question itself: Why? because, as you say, we do live these challenges and conflicts—they are the life we are living, individually and in our many communities, in the culture at large. I don’t see these stories, or stories or novels generally, as thematic discussions of issues or problems, but as invitations into imagined moments of variously imagined lives, and here, in particular, like snapshots or little videos or even a song, a unique if imaginary record of where we are living, a handful among millions, and a reminder not to forget. Wherever we fit in the complex mandala of our culture, we are affected by everything that happens, to everybody. We may like to deny this, or we may insist upon one aspect of it or position within it to the exclusion of all others, or we may prioritize our own experience of injustice or pain over another’s, or another’s over our own, but wherever we’re located, the reality is that all of these troubles afflict us all, even when we are far from their immediate consequences, or imagine we are. We are all made by each other, and no matter how powerless we may be or feel individually, we are each still contributing to the reality that extends endlessly beyond our own experience. Maybe the stories suggest this—there are a few quiet interconnections among them—but this is part of the understanding that unites them and that they share.

How has the practice of Zen infiltrated your writing processes? Has it influenced your form and content in any way?

I’ve answered variations on this question several times in recent years (for example, here, here, and here), and it’s interesting to notice how the answer changes. These days my life in Zen and my life in writing are all just this one life. And during the growing season, which is more than half the year here, this one life includes the life of a backyard vegetable gardener too. In 2016, when I stopped returning to San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm, where I trained and where my teacher lives, and settled on Pittsburgh as my landing place, I wanted to set up a life that could sustain both practices together, no longer alternating between the two. So now I host a small sangha here at my house and have hours and days given solely to formal Zen practice, and other hours and days given solely to writing, or to reading and editing and all the activities surrounding writing, such as answering these questions. These two activities, writing fiction and practicing Zen, mostly look different on the outside, but both are right here. Zen practice is always with me, and when I’m at formal practice in the zendo, writing is with me too. My life at Zen Center was sometimes like this, but without the openness of schedule that supports the actuality of composition, the relationship was out of balance. As for influence on form and content, everything in this life affects whatever I’m working on, though not always directly or in ways I’m aware of. So the answer has to be yes, but that doesn’t mean I can say how. There is certainly a greater spaciousness in my present approaches to fiction than when I was younger, but I don’t know whether this is a consequence of Zen practice so much as one of age. There may be less need to be in control as I draft now, too, more sense of allowing the pen, which is to say the mind and imagination, to wander and show where it wants to lead. But I don’t know if this is true. I’ve always had both tendencies, some sense of a defining structure or architecture, an idiosyncratic rule of some kind to follow and break, and a free flowing, experimental entry into language itself. It’s made the writing hard to categorize at times. And my Zen life too, I imagine. One more difference—I definitely have a greater appreciation of patience and my own capacity for it. I was so used to thinking of myself as impatient that it took years of Zen practice to recognize the much greater patience underneath it.

You have taught and lived in Pittsburgh. How has the area influenced your writing life?

This is a great question, especially in relation to this collection, which is set in Los Angeles, where I grew up, because it was after moving to Pittsburgh, in 1992, that I understood for the first time what it meant to be from L.A. I didn’t see it right away. I moved here from New York to join the Pitt faculty, and most of the faculty were transplants like me, as were many of the grad students and some undergrads. But after a few years I began to understand: people from Pittsburgh, really from Pittsburgh, lived where their families had lived for generations. They weren’t transients. They might have gone away for college, but many hadn’t, and those that did had come back. Many had lived here their whole lives. As a longtime wanderer among wanderers—from L.A., to Berkeley, to Yellow Springs, to Iowa City, to Provincetown, to Brooklyn, until finally to Pittsburgh (and I’m leaving the many zigzags out)—I had never actually known this depth of place-based, rooted family. In all those towns and cities, I was part of a transient or transplanted, often countercultural community—hippie, student, bohemian, artist, academic—and simply didn’t notice. But after a few years here I saw this other reality of lives deeply rooted in place, dug into time. Seeing this changed my understanding of where I had come from. Because the L.A. of my childhood was very much the opposite. Over the two generations before my birth the city’s population had gone from 50,000 to 1,500,000, and the neighborhood of most of my childhood was (as they used to say) beanfields before the war. This meant that almost everyone’s parents, the parents of the kids I knew, had, like mine, moved to L.A. from somewhere else. This wasn’t Joan Didion’s Sacramento. Our experience of “old California” was the neighborhood’s one historic building, which we called “the adobe house,” a Mexican hacienda—whitewashed, with dark wood, rather modest and small, and somehow preserved among our cookie-cutter tract homes—and which we could visit for a quarter. (As an aside, I just looked this house up on Wikipedia and the historic house I can find based on the location seems much brighter and more luxurious than the house of my memory.) Most of what I knew in that neighborhood was wanting to get out of it, to move. And I never really stopped moving. I took vagabondage for granted as the way of modern life. So coming to Pittsburgh changed that for me, in startling ways—even ways that brought me back to plant myself here—and this collection comes out of that recognition. It’s the city itself—at this point, the imagined city—that ties these separate stories together, with occasional characters and situations crossing quietly from one story into another.

Good advice and practicality are often at odds when it comes to writing. What lessons, craft techniques, or tricks do you employ most from your writing courses/syllabi into your own writing?

The most important thing to me from teaching, back in the days when I wrote syllabi, was the readings, the stories and novels and criticism read, not specific lessons of craft or technique or tricks. Writers read. And reading is a form of listening. Back in the 90s I taught a graduate fiction class on place at Pitt. We read a big range of fiction set in L.A. and Mike Davis and Baudrillard on the city, along with Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. We read to study the many ways a particular place was established and evoked, and from week to week the students wrote exploring another place of their own choosing, consciously drawing from approaches observed in the novel or stories we had read together. I was already beginning to want to write an L.A. book, but I didn’t know yet what it would be or when I would be ready to write it. At that point it was twenty years since I’d lived in California at all. But I knew L.A. was coming up for me as a source and a subject, and the class gave me a way to read a range of what others had written and to reflect on their representations of L.A. as a place. Also in the 90s at Pitt, the poet Lynn Emanuel and I created a class we called “Open to Experiment,” based around readings and provocations, with weekly writing assignments, which Lynn and I did along with the students. Most of the pieces I wrote for those assignments have been published in magazines, though not as a book. The Gunman & The Carnival also includes a few stories and parts of stories that developed out of my responses to prompts I’ve given in my Zen and writing workshops, and also in response to prompts offered by other writers here in Pittsburgh, specifically the poets Deborah Bogen and Jeff Oaks. The thing about writing from prompts, for me, is that I tend to respond to them fictionally, within the imagination of a story or even a novel already in progress. Students aren’t always receiving a prompt with this intention, but working more immediately perhaps, without using that kind of frame. Either way, receiving a prompt and writing in response to it, receiving our own response, as we write it and again as we read what we have written—these are also forms of listening, and that’s what seems most important to me. I don’t approach any of this kind of work as a lesson in craft or technique or as a trick, but I do like the sense of a provocation—an occasion to begin. And maybe, after all, that is a kind of trick.

As a writer of both novels and stories, do you believe that a collection of stories can do things that a novel cannot? How do you decide to form something into a novel from a story and vise versa?

I don’t think I think about form in this way. And I’m sure I don’t see decision itself as a rational calculation—I may try to make decisions in that way, but it’s not going to work. (Haven’t neuroscientists demonstrated that a decision comes first, and our reasons for “making” it only kick in after?) Sometimes a story is a story because it comes with a strong desire to write something that can be completed rather than going on and on for some unknown length of time. And sometimes it can’t be completed as a story, but has to be something longer and more complex. I’ve read novels that are essentially short stories spun out for a few hundred pages. And maybe some short stories are essentially novels. My experience has been that each piece or book or project is unique. How a piece arises, and in what form, seems both organic and mysterious to me. A piece of writing begins, and then it ends. Sometimes it ends but isn’t finished yet. Does it need more in the middle? Is it the first piece of many? Is it part of something larger? And so on. When I started China Blue, I was writing a story only, based on the myth of Psyche and Eros. But then the story was finished, and I had more to do—with the characters and the Provincetown setting and that moment in time. Isabel was more calculated, designed as a novel with so many chapters and so many pages per chapter and various tricks (yes) to get it to move along, and it found its life despite all that, not because of it. The tricks were just to get myself to move along, not the book. Sorrow was born whole, in concept as a novel, inspired by reading Julia Kristeva’s Black Sun. The Martyrs, The Lovers started as research for a nonfiction book (see Necessary Fiction Research Notes), which I abandoned, only to see the subject return because of the deaths of Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian, and the subject as I saw it contained too many questions and mysteries and layers of history to fit into a short story—it had to be a novel. Gunman started with an intention to return to L.A. through stories, to reimagine L.A. It was an idea for directing my imagination, for locating myself in some aspect of place, but it wasn’t the germ of a novel. This came from a kind of listening too, going back to the earlier question—listening to a kind of yearning for the old place in its new form. Although I hadn’t lived in L.A. in decades, I had visited enough to feel how different the contemporary city is from the city I grew up in. And I think we all have a mental L.A. in our cultural experience, just as we have a cultural experience of Paris or New York, one we may recognize only on arriving in the place for the first time. One or two of the stories may be a little older, but the collection as such started when, shortly after re-reading Day of the Locust, I began writing “Nathanael West Died Unknown,” just as the news was filling with 50-year memorials to Bobby Kennedy. In challenging West’s Faye Greener I was also challenging his vision of L.A. And I’m interested in how these mental and cultural images that we carry around with us, often without noticing, interact with the reality we encounter in presence in the body, how they have to change as life changes. As our shared public world kept filling with new traumatic events—the pandemic, the killing of George Floyd, wildfires, multiple mass shootings—these events had to enter the stories too. And maybe this is something stories can do more easily than a novel, respond more immediately to sudden changes. I heard Michael Cunningham say recently, at a reading for his new novel Day, that he was halfway through writing a different novel when covid hit, and suddenly that novel couldn’t continue. My daughter had a similar experience with a screenplay she felt she had to abandon after 9/11. Suddenly the culture is so changed that it interrupts and challenges the work you’re doing. Maybe stories—and poems too—are more flexible in being able to respond immediately than longer forms. I don’t really know. But I do know Gunman was always aiming to be a collection, a mosaic or collage in some sense, and the occasional threads that weave across the stories came out of the stories themselves. They were never wanting to be a novel and despite my novelistic impulse to make connections, I wasn’t aiming to write one. If I could afford to live in L.A. again, maybe an L.A. novel would get born out of that, or maybe out of something completely other that I can’t see at the moment—a whole new next life?

More from Catherine Gammon…