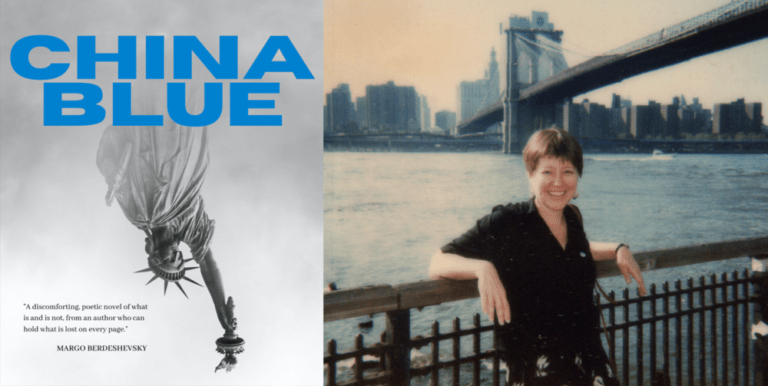

About the Author: Catherine Gammon moved to Pittsburgh from New York in 1992 to join the creative writing faculty of the University of Pittsburgh. In 2001 she left Pitt to begin residential training at San Francisco Zen Center, where she was ordained as a priest in 2005. After several shorter stays, Catherine returned to Pittsburgh for good in 2016. Her novel Sorrow, published by Pittsburgh’s Braddock Avenue Books in 2013, was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award. Her novel Isabel Out of the Rain was published in 1991 by Mercury House, and her shorter fiction has appeared in literary journals for many years.

From the Publisher (on China Blue): “In the early 1980s, teenaged Tess runs away from home to New York City after a fortune-teller dredges up a memory she’d dismissed as a forgotten dream. Tess’s Mama struggles to understand the reason for her disappearance as other characters battle with the consequences of US wars in Central America, the mistakes of the surveillance state, as well as with alcoholism and what ‘truth’ means to them. Winner of the Bridge Eight Press Fiction Prize, Catherine Gammon’s musical novel is rich with fully-formed characters, generous with real feeling, and intentional with its prose.”

Save the date for an online celebration: June 24, White Whale Books, with Lynn Emanuel, Toi Derricotte, William Lychack, and Catherine Gammon!

Advance Praise for China Blue:

“Catherine Gammon’s kaleidoscopic and complex novel China Blue is both gorgeously and fluidly written and immovably fixed by the boundaries of human suffering. Taking place in the shadow of the Vietnam War and during the American destabilization of El Salvador, China Blue assembles its montage from the jagged lives of women and men entrapped by addiction, poverty, and sexual obsession. Gritty, sorrowful, clear-eyed, and vivid, China Blue is a powerful book, and one of uncompromising originality and integrity.” —Lynn Emanuel, author of The Nerve of It, Noose and Hook, and Then, Suddenly—

“A discomforting, poetic novel of what is and is not, from an author who can hold what is lost on every page.” —Margo Berdeshevsky, author of Before the Drought and Beautiful Soon Enough

“A haunted dream of a book—by turns poetry, philosophy, love story, always beautiful, enigmatic, strange—China Blue is a fiery declaration of all that is inexpressible about desire and loss and the need to find a home in a world in which even the most solid and real of things feel often less than completely solid or real. ‘The sky is paper. The wind is up. The trees are rasping.’ And Catherine Gammon brings this world to life like a demon.” —William Lychack, author of Cargill Falls and The Wasp Eater

You are the mother of a daughter, and you and your daughter lived together in Provincetown and New York during the time period China Blue is set in. Can you comment on the ways the book does and doesn’t represent your own experience?

You are the mother of a daughter, and you and your daughter lived together in Provincetown and New York during the time period China Blue is set in. Can you comment on the ways the book does and doesn’t represent your own experience?

Thankfully, Tess’s experience is not my daughter’s, and Holly’s loss as a mother is not my own. But their story does reflect the times and places in which I was the mother of a teenage girl, the culture and the dangers and fears, and like the two mothers in the novel, during the early 1980s I was living my own active addiction to alcohol and generating the emotional chaos and denial that come with that.

When I first wrote “Night Vision,” the opening chapter of China Blue—something like forty years ago now—I imagined I was retelling the Greek story of Psyche and Eros, casting myself and people I knew like actors in a film. Until an early reader spoke the word back to me, I had no idea that there was an issue that could be called incest in that story, or more fundamentally that I myself lived with unexamined issues of incest or sexual or emotional abuse in my own childhood. In this way, this writing was an early revelation, in the sense that dreams reveal, of problems of my own psychological development, starting in childhood and ongoing.

Late in the novel, Katie Roberts, the more shattered alcoholic mother in the book, turns the light back onto Holly and tells her to look at herself. When I first wrote that challenge I was myself still drinking and in denial of my alcoholism. The scene is entirely fictional, between two fictional characters, and at the same time, the writing voice, the writer, was telling me, the struggling human, to wake up.

So I have an old, deep affection for these characters and their troubles, because the early drafts that gave birth to them, their first appearances in my imagination and in fictional language, were steps toward recovery for me. And I couldn’t finish the book, even in a preliminary draft, until I found recovery, which happily now has been continuous for many years.

So I could say about the novel that everything is invented and at the same time true, which may be what it means to be fiction: it claims to be true and not true both, independent of any relation to ordinary factuality.

You wrote China Blue originally in the early 1980s, the period in which it is set, and you’ve certainly revised it since then, but although a few individual chapters were published in literary magazines at that time, the novel remained unpublished until now. Isabel Out of the Rain (Mercury House, 1991) takes place in the mid 80s and Sorrow (Braddock Avenue, 2013) in the early 90s. How would you compare or connect these earlier times with the present? How does China Blue specifically speak to the times we’re currently living in?

I came of age at a time when many people, especially young people, were becoming suspicious of authority, reductionism, and essentializing—if I can say this without essentializing an entire generation. I think we also became sensitive to the elusiveness of truth, recognizing both that what we see depends on where we’re standing and the many ways in which those in authority use this elusiveness against the rest of us, especially those farthest from power.

Recently there’s been a tendency to look back on the 1980s as a celebration of greed and the victory of “America” over Soviet communism. But at the time there was an intense resistance to that way of life and that understanding, and this resistance gets forgotten with the victory of Reaganism. And the victory of Reaganism eventually brought us the last four years, along with decades of climate change denial, and it led to the policies that became the new Jim Crow and exacerbated a world of other problems the current administration is challenged to face and solve. And, of course, Reaganism had older, deeper roots, too. So fundamentally the story doesn’t change.

I won’t go on a political rant here, but China Blue was a countercultural book—they’re all countercultural books—and maybe for a moment now we have a window when the same countercultural forces are risen sufficiently to be recognized again, and possibly more effective this time around. Writing in the 1980s, I didn’t see sexual abuse and violence against young women and girls as separate from imperial power and war, and I didn’t feel called upon to justify this juxtaposition. I hope that by now we are able to recognize that the abuses of power that have provoked #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter and #Occupy and movements for peace and climate justice are inseparable from one another. And I hope we can see these interconnections in their complexity, with subtlety and nuance, free of the polarizing, essentializing, reductionist simplifications so familiar in tweets and memes. Novels can still help with this, and I hope not only in the forms of classical realism but also in more modernist and experimental modes that allow for poetry in the prose.

If China Blue unfolds in a world of countercultural experience, in a decade often caricatured, or forgotten in its complexity, one way to conjure it—whether to imagine or to remember—might be through its music. Were you listening to anything in particular when you were writing? Would you recommend a playlist?

I can’t say I was writing and listening at literally the same time, but certainly the music I was listening to in the early and mid 1980s pervades my feeling for this world, the characters and their stories. A playlist would have to start with the Talking Heads—Remain in Light and Fear of Music, especially “Listening Wind” and “Cities.” Then Brian Eno and David Byrne, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, especially “Help Me Somebody,” and Laurie Anderson, Big Science, in particular “O Superman.” Finally, Jean-Michel Jarre’s Oxygene, Philip Glass for Glassworks and The Photographer, and Inti-Illimani, especially Imaginacion and Hacia La Libertad.

Would you like to offer a last word about the cats?

I would. As a cat person, I enjoy seeing a cat or two appear in a work of fiction. Cats are generally part of life as I know it, so naturally there are cats. And these particular cats are based on actual cats of my acquaintance in those days.

At the same time, because this is a work of fiction, each cat functions in relationship with the part of the novel in which it appears. The first cat, the Provincetown cat, is an orange Maine coon, and a careful reader might notice that his eyes are either gold and yellow or green. This ambiguity mirrors the Provincetown action—is it this, or is it that?—depending on who’s seeing, who’s telling.

In contrast, the New York cat, Violet, is definitively drawn—a survivor of the street, rescued with a bleeding stump where her tail should be, and as one early reader read her, an iconic, almost magical being. And Violet too serves as a mirror for the human action in her world—for Tess’s life and survival.

China Blue is available to order from Bridge Eight Press, from local booksellers, and on Bookshop.org.

Save the date for an online celebration: June 24, White Whale Books, with Lynn Emanuel, Toi Derricotte, William Lychack, and Catherine Gammon

For more from Catherine Gammon, check out our our earlier feature on Sorrow.