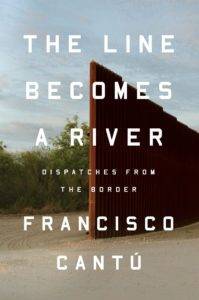

From the Publisher: “For Francisco Cantú, the border is in the blood: his mother, a park ranger and daughter of a Mexican immigrant, raised him in the scrublands of the Southwest. Haunted by the landscape of his youth, Cantú joins the Border Patrol. He and his partners are posted to remote regions crisscrossed by drug routes and smuggling corridors, where they learn to track other humans under blistering sun and through frigid nights. They haul in the dead and deliver to detention those they find alive. Cantú tries not to think where the stories go from there.

Plagued by nightmares, he abandons the Patrol for civilian life. But when an immigrant friend travels to Mexico to visit his dying mother and does not return, Cantú discovers that the border has migrated with him, and now he must know the whole story. Searing and unforgettable, The Line Becomes a River goes behind the headlines, making urgent and personal the violence our border wreaks on both sides of the line.”

Don’t miss out: Cantú will be visiting the City of Asylum Bookstore at Alphabet City on February 17th!

“A must-read for anyone who thinks ‘build a wall’ is the answer to anything.”—Esquire

Why did you decide to join the United States Border Patrol?

Why did you decide to join the United States Border Patrol?

When I first considered signing up for the Border Patrol, I was at the point in my life when I’d become completely obsessed with the border. For several years I had been investigating it in every way I could think of: I had been reading about it, dreaming about it, visiting both sides whenever I had the chance. I felt driven to understand it in every possible way. I had just spent four years in college studying immigration and border issues, and I felt like I was still filled with all these questions. I felt the only way to answer them was to see the realities of the border for myself, to be out in the desert and out on the line day in and day out. Other being drug runner or a migrant, the Border Patrol seemed like the only way to do that.

Was there any point during your time with the Patrol where you felt you were doing the right thing, in spite of the knowledge that the majority of the people you were arresting only meant to improve their own lives? Did you ever enjoy your time in the Patrol?

At the time, I told myself that it was a job that someone was going to have to do no matter what, so why not me? In this naive and idealistic way, I thought that since I could speak Spanish, since I had lived in Mexico, since I had all this knowledge of the border from college, that somehow I’d be able to help people, make their experience less traumatic, be a force for good within the agency.

At the time, I told myself that it was a job that someone was going to have to do no matter what, so why not me? In this naive and idealistic way, I thought that since I could speak Spanish, since I had lived in Mexico, since I had all this knowledge of the border from college, that somehow I’d be able to help people, make their experience less traumatic, be a force for good within the agency.

There were definitely parts of the job I enjoyed-being outside, learning to understand and read the landscape, and there was something exciting about the detective-like elements of the work. But to be honest, I rarely ever felt like I was truly helping people. A year or so after being in the field, I got training to be an EMT, but even when I literally helped to save someone’s life, it was hard to feel good about it because I’d be taking them back to a cell, to be kicked back to a place they were trying to flee.

There is a moment in the book where you are telling your supervisor that you are leaving the Patrol to go back to school, but you actually wanted to say “this work is not for me.” After all you’d seen and experienced, what finally made you come to that conclusion? Why did you resign from the Border Patrol?

The first signs I had that the job might not be for me came in the form of nightmares. I had these dreams where I would come up on dead bodies in the desert, or where people I had arrested and sent back would return to me. For years I just sort of ignored them, but they never went away, they just became more and more violent and jarring.

There was this one recurring dream I had more than any of the others, where my teeth would just fall out of my mouth. A few years after I started having these dreams, I went in for a dental appointment and the dentist told me that I’d been grinding my teeth in my sleep, that I was grinding so much that I had worn through the enamel on my molars. Then things reached the point where I literally broke down on my way home one night and had to pull over on the side of the road to weep. That’s when I finally had to look at myself and say “something’s wrong.”

Your great-grandparents and your grandfather (who was an infant at the time) crossed over from Mexico. Did your family history have any influence over your curiosity about the border, or your decision to work in the Patrol?

I grew up at somewhat of a distance from this part of my identity. A lot of people with mixed identities might have experienced something like this. For me, it actually started with my mother: her father was Mexican, but her mom left him and moved away with her when she was still just a child, so my mother didn’t grow up in Mexican culture. She was even made to feel ashamed of it as she was growing up. So I was very rarely reminded of my Mexican background until in high school, when I first started taking Spanish classes. I suddenly became conscious of the fact that I had a Mexican name and that this meant something about my heritage.

The last sections of The Line Becomes A River are about a man named José, who was not allowed to return to the United States after crossing back into Mexico to attend his mother’s funeral. Are you still in touch with José, and was he able to cross over again?

I wish I could share with you the rest of José’s story, but the truth is, like so many others in his situation, he is living a precarious life, made worse by the current climate on the border. For me to say where he is, what he’s doing, that would make him unsafe. What I can tell you is that José’s story is something that truly transformed me-we hear over and over again about the generalized challenges that face the millions of undocumented migrants living in our country, but nothing can be as impactful as an individual story.

That’s why José’s story feels so central to this book, it gave me much deeper, more devastating and personal understanding of the extent to which a border can rip through people’s lives. We need to hear stories like this, told preferably by the people who are living them, and we need be ready to listen to and amplify their voices.

Did you always know you wanted to be a writer?

I joined the Border Patrol looking for answers. Of course, I never found those answers, I only came away with more questions, and that’s what led me to write about the experience-it was my way of trying to make sense of it. Before then, writing had always been a sort of afterthought. I had long been a literary nerd, someone totally fascinated by the literature that touched on borders, immigration, and exile, but I never really saw myself writing as anything more than a hobby, until finally it became a compulsion, something I had to do.