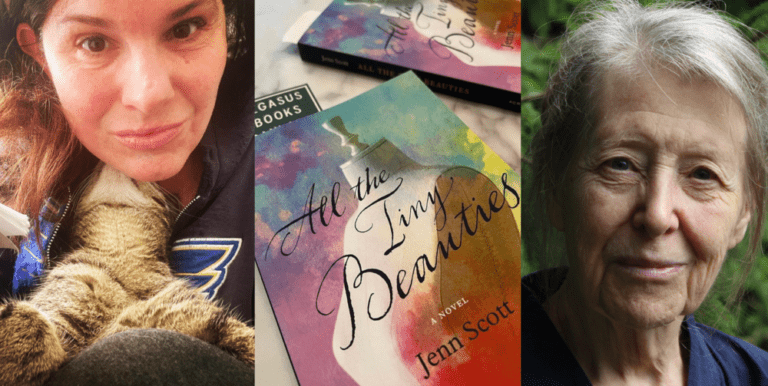

Jenn Scott received her MFA in Fiction from the University of Pittsburgh and has published stories in many journals, including Fiction, Gettysburg Review, Cincinnati Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Santa Monica Review, and Gulf Coast. Her debut collection of stories, Her Adult Life, was long-listed for the PEN America/Bingham Award in 2018. A native of Pennsylvania, she now lives and writes and roots for the Steelers in Oakland, California. Her most recent novel is All the Tiny Beauties.

From the Publisher: “Set in Oakland, California, All the Tiny Beauties begins with a kitchen fire that sends the reclusive Webster Jackson to the home of his new neighbor, Colleen, who discovers him on her doorstep wearing a lacy peignoir, his house in flames. Unwilling to take responsibility for the lonely eccentric, Colleen reaches out to Webb’s estranged daughter, Debra, and also helps him find a live-in companion, a young adult reeling from the loss of her childhood friend.

Moving among perspectives and generations, we see the longings and vulnerabilities that drive and impede these characters as their stories intertwine—Webb’s first love clashing with his last; Colleen embarking on a secret affair with Debra; the older Webb and his young housemate, Hannah, forming a bond over tragedy, guilt, and his passion for baking.

Confronting the many ways they’ve failed others as well as themselves, Webb, Colleen, Hannah, and Debra slowly find ways forward and ways out. While exploring the fragile nature of our connections to one another, All the Tiny Beauties asks larger questions about the constraints society imposes that warp and wound, leading us to deny those things that make us wholly ourselves…”

Catherine Gammon’s new novel is The Martyrs, The Lovers (now available to pre-order on Bookshop.org). Her previous novels are China Blue, Sorrow, and Isabel Out of the Rain. A new story collection is forthcoming from Baobab Press in 2024. Catherine taught at the University of Pittsburgh throughout the 1990s, before beginning residential Zen training in California. She lives again in Pittsburgh.

Read our Littsburgh Q&A with Catherine Gammon

Start reading Sorrow by Catherine Gammon…

From the Publisher: “The Martyrs, The Lovers circles the mysteries surrounding Jutta Carroll’s death—probing her origin story, the rise to personal political stardom, and the fall into anxiety and public decline—all the while exploring the forces and motivations that drive political passion and activism, and the counterforces, material and psychological, that constantly threaten progress.

The Martyrs, The Lovers is loosely based on the life and 1992 death of the German Green Party founder and activist Petra Kelly with her partner Gert Bastian. The challenges to environment, peace, justice, and feminism that informed these lives and deaths—in the world of the fiction and in reality—challenge us more than ever today…”

Catherine: You revealed in an earlier interview that this novel started, as novels often do, as a short story that was too big for the form, and that this generating short story is not the beginning of the novel, but its end—that the novel became a way of working your way to the short story, earning it in a sense. I found this fascinating, in particular because there is something so stunning and utterly subversive about the way the novel comes to conclusion. What I mean by subversive is your embrace in All the Tiny Beauties of the most radical acceptance of everyone as they are, of allowing people to be just themselves, without trying to fix them or improve them or even to save them in any way. And although a compassionate sense of this acceptance is present from the beginning and in your approach to all the central characters, somehow it’s only at the end that the depth of the case you are making fully emerges. And I hope we can talk about this without introducing spoilers.

Catherine: You revealed in an earlier interview that this novel started, as novels often do, as a short story that was too big for the form, and that this generating short story is not the beginning of the novel, but its end—that the novel became a way of working your way to the short story, earning it in a sense. I found this fascinating, in particular because there is something so stunning and utterly subversive about the way the novel comes to conclusion. What I mean by subversive is your embrace in All the Tiny Beauties of the most radical acceptance of everyone as they are, of allowing people to be just themselves, without trying to fix them or improve them or even to save them in any way. And although a compassionate sense of this acceptance is present from the beginning and in your approach to all the central characters, somehow it’s only at the end that the depth of the case you are making fully emerges. And I hope we can talk about this without introducing spoilers.

Jenn: I feel compelled first to acknowledge your description of the novel’s conclusion as “stunning and utterly subversive”—which, if I could cherry pick a response to the ending, yours would be my dream. So, thank you! I’ve mentioned that I spent too many years writing this novel—so many years, writing—and working towards this particular ending, which was for a very long time the only thing I knew in a sea of things I absolutely didn’t know. I hadn’t thought about it in terms of making a case for radical acceptance, but feel very drawn to this as a way of understanding why writing this book took so long. I knew this particular action at the end was a hard sell, something—to use your words—I needed to make a case for: why does this happen? There’s a moment at the end of the book when Hannah, one of the central characters who is embroiled in this action (of which we cannot speak), acknowledges that she will always be the person who made this choice rather than a person who made a perhaps easier, less fraught decision. She accepts this about herself, that she is this person and that this act is now part of her history. I think the book from its earliest days was invested in this balancing act of regret and acceptance of one’s choices, this trying to honor the fact that as we grow older, we accumulate memories both special and damning, and that both inextricably compose our lives. One of the reactions I’ve experienced most from readers is their genuine enjoyment of having spent time with these characters. They then usually say something like, “I even loved Beverly!” At superficial glance, Beverly is a clear antagonist in the novel, but really she is as flawed and damned as all of us, a product of society, a woman with quelled desires, like so many of us. But she’s human, and she’s complicated. I didn’t need people to like her, but I wanted them to maybe understand her. To quote you, I made a case for her and her actions, and I tried to do this for every character. So this idea of radical acceptance of everyone as they are, and the ending of the book as the ultimate culmination of this, pleases me quite a lot.

Jenn: I feel compelled first to acknowledge your description of the novel’s conclusion as “stunning and utterly subversive”—which, if I could cherry pick a response to the ending, yours would be my dream. So, thank you! I’ve mentioned that I spent too many years writing this novel—so many years, writing—and working towards this particular ending, which was for a very long time the only thing I knew in a sea of things I absolutely didn’t know. I hadn’t thought about it in terms of making a case for radical acceptance, but feel very drawn to this as a way of understanding why writing this book took so long. I knew this particular action at the end was a hard sell, something—to use your words—I needed to make a case for: why does this happen? There’s a moment at the end of the book when Hannah, one of the central characters who is embroiled in this action (of which we cannot speak), acknowledges that she will always be the person who made this choice rather than a person who made a perhaps easier, less fraught decision. She accepts this about herself, that she is this person and that this act is now part of her history. I think the book from its earliest days was invested in this balancing act of regret and acceptance of one’s choices, this trying to honor the fact that as we grow older, we accumulate memories both special and damning, and that both inextricably compose our lives. One of the reactions I’ve experienced most from readers is their genuine enjoyment of having spent time with these characters. They then usually say something like, “I even loved Beverly!” At superficial glance, Beverly is a clear antagonist in the novel, but really she is as flawed and damned as all of us, a product of society, a woman with quelled desires, like so many of us. But she’s human, and she’s complicated. I didn’t need people to like her, but I wanted them to maybe understand her. To quote you, I made a case for her and her actions, and I tried to do this for every character. So this idea of radical acceptance of everyone as they are, and the ending of the book as the ultimate culmination of this, pleases me quite a lot.

Catherine: There are many parents in this book, mostly seen through the eyes of the adult children who have loved them and suffered from their parenting, and I was struck particularly by the mothers, who are generally either obsessively controlling, even abusive, or fundamentally absent. Only Debra seems to be engaged and accepting as a mother, but we see her more often in her absence from her son than in her presence. The fathers also seem to be controlling and abusive or absent. I would even suggest that this absence is at the heart of all the relationships, an absence in which your characters often suffer, but which also allows them to find the freedom to be themselves. Could you talk about this?

Jenn: I would say unequivocally, yes, absence is at the heart of the relationships, that each character’s relationship to the absence of another character becomes its own defining relationship in the book. It’s interesting to hear you acknowledge that these absences allow characters to find the freedom to be themselves. This was always a central point for me when I considered the character of Debra. It’s hard to talk about without giving key plot points away, but readers learn early on that Debra is estranged from her father, Webster. I think Debra in particular, especially at the end of the novel, has found the freedom to be herself, and I would argue that this freedom is closely aligned with—is in fact dependent on—Webster’s absence. That because of his absence, she becomes who she will become. And even though you mention that Debra is perhaps the most engaged mother in the book, her son has no knowledge that she had a different father than the one he knows, or that she spent the first twelve years of her life in Oakland, not Los Angeles. So in a sense, Debra is absent from her own narrative—or Beverly, her mother, has made choices that have absented Debra from her own narrative. Webster himself is an interesting case because he loves people so much—he loves Debra, he loves Hila, he is devoted to Beverly—but he struggles to be present with them, to engage with these people he loves in sustained, meaningful ways. It’s easier for him to have a relationship to the absence, than to the people themselves, and much of the book is about his relationship to the pervasive absences in his life.

You develop your multiple major characters, their multiple points of view and multiple timelines, not in chronological order, or psychological order, but in a gradual, apparently intuitive accumulation that for me was one of the beauties of the book. And it seems fitting to appreciate this slow growth and abundance in terms of the many domestic arts All the Tiny Beauties quietly celebrates—the sewing, cooking, baking, gardening that help the characters find connection with one another. Can you say something about this support, and maybe contrast these new domesticities to the failed domesticities of the book’s patriarchal marriages?

You develop your multiple major characters, their multiple points of view and multiple timelines, not in chronological order, or psychological order, but in a gradual, apparently intuitive accumulation that for me was one of the beauties of the book. And it seems fitting to appreciate this slow growth and abundance in terms of the many domestic arts All the Tiny Beauties quietly celebrates—the sewing, cooking, baking, gardening that help the characters find connection with one another. Can you say something about this support, and maybe contrast these new domesticities to the failed domesticities of the book’s patriarchal marriages?

Jenn: Ah, I did very much want this book to be a celebration of home, centering as it does on a protagonist who does not leave his home for at least a decade—at least, not in any real way—before he catches his kitchen on fire. He leaves through no choice of his own, but because he’s forced to. I always imagined Webster as a man who honors the idea of home, who sincerely loves the things home offers him. He loves to cook, to nest, to feel coddled by home—but perhaps it has made him feel too safe, perhaps it’s damaged him. It’s funny, because right as I finished the book, quarantine happened. I live in Alameda county and we were the first county in the country to issue a shelter in place order. Right before this shelter in place happened, I’d been having a hard time writing and working and trying to balance these things.

I remember thinking, I just want my house to contain me like a cocoon. And, voila, a miracle happened and I got my wish to just stay home. I thought, Oh, I just wrote a book about a man who is essentially a hermit, and now I get to give this hermit thing a try, myself. Everyone else was struggling, having a hard time being at home, and I thought this was the best thing that could happen to me because I needed to be still and quiet and I needed home to contain me (much like Webster). I’m a waiter, and indoor dining was closed in the Bay Area for quite a long time. I didn’t go back to work for another year and a half. Three years after this shelter in place order, I’m only now considering the ways in which staying at home so long changed me, or made me weirder. It’s subtle, but it’s there.

This is a very long way of saying that while the book celebrates home, there are nefarious underpinnings just below the surface, both in the complicated security of home—is it a haven, really, if you’re too afraid to leave it?—as well as the failed domesticates you mention. I honestly hadn’t thought about how every patriarchal marriage struggles until you mentioned it. The patriarchal marriages in this book are a mess. There’s quite a few couples sharing homes and purportedly building lives together while being remarkably distanced from one another. The domesticities you mention (the gardening, the sewing, the cooking, etc.) are at times a source of comfort and bonding, but they are frequently battlegrounds. I have suspected that had Beverly and Webster been less rigid in their domestic roles, perhaps their marriage would have worked. Or, it would have sufficed. She never would have been comfortable seeing him wear a dress, but if only she could have let him cook some dinners, or even admitted, “Actually, I hate cooking, I hate cleaning, I hate all of these things,” perhaps their story would have been different. Webster’s relationship with Hila is antithetical to his marriage to Beverly. It’s incredibly unconventional—they spend years together, and she refuses to even give up her apartment—but it’s characterized by her pure acceptance of him, her disavowal of rigidity, which is of course a defining quality of patriarchy. The fluidity and ease of their relationship is to me one of the most beautiful things in the book. I think it’s one of my favorite things about the book.

Catherine: Let’s talk about fire. Food depends on fire, and fire itself becomes a motif in All the Tiny Beauties, starting with the initial accident that brings Webb into contact with Colleen, setting off the chain of connections and re-connections that are the novel. Fire as apocalypse is a familiar element of California fiction, and while you do offer a few apocalyptic fires in the background here, from the bragging of Webb’s deluded father to the reality of the Oakland hills fire of 1991. What I find interesting in your use of these fires, though, is how they serve as another element of domestic reality. The characters encounter them, live with them, as part of everyday existence, and if they are apocalyptic it is not in any grand social-political-historical-cataclysmic sense, but again in terms of small personal domestic cataclysm that can change a life and lives forever.

Jenn: I have a deeply rooted fear of fire that borders on paranoia, and which stems very specifically from my own personal experience. When I was in second grade, two nights before I received my first holy communion, I woke to the sound of the downstairs neighbor knocking on our apartment door, alerting us there was a fire in the building. The fire alarms were broken, hadn’t gone off. This man happened to be having a party. He and his partygoers had smelled smoke and soon were knocking on all the doors in the apartment building—it was a three floor building—to rouse everyone and tell them to leave. I still remember that the man who had knocked on our door that night had contributed a whole dollar to my donation container for the Missions. I’d been very impressed by this. That night, he lost everything he owned, and we very nearly did. My communion dress survived, and I remember wearing it several days later, and that it still smelled of smoke. I remember, too, during one of the practices before the actual event, some people sitting in the pews pointed at me and said, “That’s the little girl whose apartment caught on fire.” I remember this very acutely forty years later. To this day, the smell of fire causes me a lot of anxiety. So, yes, fire is a very personal and essentially domestic thing to me, which is perhaps why the lens through which the fires in the book are viewed is an intensely personal one. The Oakland Hills fire in 1991, recounted in the book, was, until recently, the most destructive California fire. By the time I moved to the state in 2001, ten years had already passed, and I arrived knowing nothing about this fire, though the residues of the angst people had experienced were still there. I worked with someone who had lost everything in this fire, and I remember his residual anxiety about it. What’s interesting, too, is how the landscape of the Oakland hills changed as a result. The houses before the fire were smaller, there were more apartment buildings. The hills had a more middle-class aesthetic. When people rebuilt their lost homes after the fire, they received a lot of insurance money and built larger, more imposing houses. In the book, Hila’s duplex is gone after the fire. It no longer exists. And now the Oakland hills fire is not the most destructive fire in California history and because there have been so many recent wildfires, my feeling towards fire has become increasingly apocalyptic. There have been days in recent years where you can’t leave the house without an N-95 mask, where you obsessively check the air index to see if it’s safe to be outdoors. Days when the sun glows orange, when ash falls from the sky like snow, when the newscasters are saying, “Don’t hike, cancel school!” There was an actual day in 2020 when the Bay Area sky was blood orange from the fires and my house appeared pitch black in the middle of the day. It definitely had a more “end of the world” feel than anything which appears in the book, and probably if I were to write about it, knowing me I’d nix the apocalyptic vibe and write about stubbing my toe in the dark. Not really, but I guess I tend towards the small and personal.

Catherine: Like your main characters, Hannah, and her friend Sam, you’re originally from northeastern Pennsylvania, and you have lived in Pittsburgh. Is there a way you see your Pennsylvannia background playing into the novel and your vision of—and for—the characters, the Californian characters too? So many cultural winds blew sooner, hotter, faster in California than in Pennsylvania in some of the years you’re dramatizing, and I wonder how that might have affected your sense of Webb’s family, for example, or of Beverly. Part of what I’m thinking about here is that, in contrast to you, I now live in Pittsburgh but grew up in Los Angeles and later lived in Berkeley for a number of years—so our trajectories make something of a mirror image—and this led me to wonder how much of your imagining of the earlier California generations might have been shaped by your knowledge of those generations in Pennsylvania. They do have a flavor that seems quite different from the older generations of Californians I knew in those years (including my own). They—and we—are all distinct characters, of course, and with different social backgrounds, whatever the geography or generation, and generalizing is never fair—so this isn’t an observation about the characters, so much as a curiosity about your process in imagining them.

Jenn: This is a really good question, and something I’ve considered—though maybe not within this exact framework. I’ve grappled with this being a potential flaw of the book, that it doesn’t engage with the political currents of the time. That here is a man, a crossdresser, who lives in Oakland, California during a time when there is a lot unfolding just across the bridge in terms of gender and crossdressing and trans rights. There are people who are doing what he’s doing, who are advocating for it, who are celebrating the beauty of fluidity in gender, but at no point does Webster engage with or pursue or forge any relationships outside of home that might validate his needs, or put his needs in conversation with others’ needs. I think this circles back to your earlier comment about celebrating home, and my response about its nefarious underpinnings. Writing this book and thinking about his character, I simply didn’t see Webster Jackson as a man who’d explore the possibilities available to him. He’s fundamentally a man of inaction rather than action. He’s been very repressed about these particular wants and desires. He’s also married to Beverly, an incredibly traditional woman, and he has decided that committing to the traditions of marriage will “save” him and help him be a “proper” man. So I think this Bay Area political scene is something he’s very distanced from. The closest he gets to being someone who can willingly explore it is in his relationship with Hila—beautiful, wonderful, Hila!—but he’s so repressed even in his ability to love and be loved by her that even this has its limitations.

It’s interesting for me to consider that my arrival at this logic is perhaps an inherent Pennsylvania sensibility rather than my own determination of what I’ve believed to be true about Webster Jackson’s character. That maybe I’ve determined this to be true about his character because I didn’t live in the Bay Area in the sixties and had I lived in the Bay Area during this time, I would have written a very different book, or Webster would be a different character. I listened to an absurd amount of The Grateful Dead when I wrote this book, and sometimes it was so funny to me that I was writing a book that was concurrent with what was musically happening in San Francisco, and that the two things never intersected. Webster is at home with his wife, and the Dead are playing free shows in the Haight, but it would never occur to Webster and Beverly to drive over and catch a show because it isn’t their scene. And maybe it’s Hila’s scene—although, she would hate all the clothing people were wearing—but by then Webster is already too attached to staying home. They throw a lot of parties, but they aren’t leaving the house to do a lot of things.

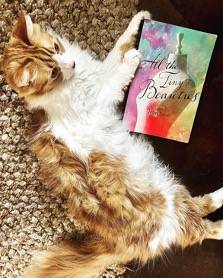

Catherine: I’m in awe of your cats, your actual cats, which I often see on Instagram, and you do manage to make extraordinary narrative use of a cat toward the end of All the Tiny Beauties. Again, no spoilers, but just an appreciation of the emotional significance, the suspense, and the resolution you build around this little creature. Any last words here?

Jenn: Ah, the scene with the cat. It’s actually one of my favorite scenes in the book. I love cats, as anyone who has looked at my Instagram, or spoken two words to me, can attest. And as a little addendum: the ending of the book—that which was the only thing about the book I felt sure about—was still the last scene I wrote. I’d put off writing it because I felt it demanded an emotional depth I wasn’t capable of grasping, but I knew one day would come when I felt I could access it. Towards the end of writing the book, my beautiful, perfect orange tabby named Spike died after surgery, and that morning I woke up at four am and thought, Well. I guess this is that moment. I sat down and just wrote that scene and just like that, the book was done. (Except it wasn’t, of course.)

This conversation also ran on Catherine Gammon’s newsletter, which you can subscribe to here!