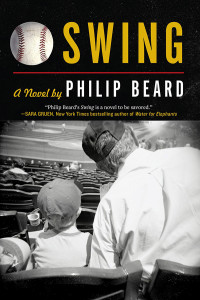

We’re thrilled to be able to share with you the first chapter of Philip Beard’s Swing (“a novel to be savored” – Sara Gruen, New York Times bestselling author of Water for Elephants). Swing is a multifaceted meditation on childhood heroes, the beauty of baseball and the power of love to heal a family in crisis — the perfect read to distract yourself from a World Series without the Pirates. Next year, Buccos!

“Mr. Beard’s Swing is just about perfect. In fact, he crushes it.” – The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

He was a man who liked to announce things, so I was saddened but not at all surprised to receive this morning in my department mailbox what could only be described as a formal invitation to his memorial service. It was mailed out, in accordance with his will, by the V.F.W. Local 70 of Riverside, PA, complete with an RSVP card and instructions to bring an appetizer, a dessert or a six-pack (bottles only). We are nearly five hundred miles away from the planned festivities—with our two children, two untenured positions, one old dog and one dying fish—and I expect that all of those things will conspire to keep us at home. But Maggie and I would both have legitimate reasons for wanting to attend: mine would be love; hers, a morbid curiosity to see the size of the casket of the man I have been immortalizing, re-inventing and, to some extent, eulogizing for the full fifteen years of our marriage. Lately, Maggie has found reasons to doubt me on a number of fronts, and I think she has begun to believe that he is a figment of my all-too-active imagination. I suppose that makes it all the more ironic that the same piece of folded, off-white cardstock that tells me he is gone will also convince my wife of his existence.

He was a man who liked to announce things, so I was saddened but not at all surprised to receive this morning in my department mailbox what could only be described as a formal invitation to his memorial service. It was mailed out, in accordance with his will, by the V.F.W. Local 70 of Riverside, PA, complete with an RSVP card and instructions to bring an appetizer, a dessert or a six-pack (bottles only). We are nearly five hundred miles away from the planned festivities—with our two children, two untenured positions, one old dog and one dying fish—and I expect that all of those things will conspire to keep us at home. But Maggie and I would both have legitimate reasons for wanting to attend: mine would be love; hers, a morbid curiosity to see the size of the casket of the man I have been immortalizing, re-inventing and, to some extent, eulogizing for the full fifteen years of our marriage. Lately, Maggie has found reasons to doubt me on a number of fronts, and I think she has begun to believe that he is a figment of my all-too-active imagination. I suppose that makes it all the more ironic that the same piece of folded, off-white cardstock that tells me he is gone will also convince my wife of his existence.

I met him during a part of my childhood that is hard to revisit, so it has been both easy and convenient to see him mostly through my children’s eyes. Allie has outgrown the stories, but Walt knows The Swinger the way she once did—as a kind of super-hero, invented to put them both to sleep with thoughts of something right and true, someone just impossible enough that they wanted him to be real. Even I sometimes have difficulty distinguishing the character I have created from the man I knew. But knowing now that he is gone, I see him very clearly. Or, at least, as clearly as we ever see our boyhood heroes.

It is early October of 1971 and I am eleven years old, standing at a bus stop at the corner of Fort Duquesne Boulevard and Sixth Street in downtown Pittsburgh. I am there alone on a school day, without permission, which adds a sharpness to everything around me: the sidewalk sparkling blood-orange in the low sun; the light breeze cooling where it had warmed only an hour earlier; the bridges across the Allegheny River at Sixth, Seventh and Ninth streets superimposed over one another in a maze of yellow iron. The Pirates, my Pirates, have just beaten the San Francisco Giants to advance to the World Series, and my father has just left us—two oppositely charged facts that make such a muddle of my thoughts that I don’t know whether to continue grinding the souvenir ball into the worn, oily palm of my glove, or throw them both into the river. My father left on a Saturday, carrying a single suitcase. On his way out, he put the Pirate tickets on the kitchen table and I sat on the window seat holding them, watching him walk to his car. My little sister Ruthie wrapped herself around his leg in the driveway and screamed. My older sister Sam pounded on the hood of his car, both hands clasped into one big fist, trying to make a dent. My mother stood unmoving in the doorway, resisting a visible urge to comfort her daughters in favor of letting my father’s departure become as ugly as possible for him.

Thinking of my mother in that same doorway again, expecting me to get off the school activities bus, is the first time all afternoon that I have given any thought to how I am going to explain my absence. I had hung on the third base railing for more than an hour after the final out to get my souvenir, so the crowd from the game is mostly gone. The few people approaching the bus stop are heading home from work or shopping: a slender, young black woman in a tailored white pantsuit holding her child’s hand; two businessmen carrying briefcases, laughing and talking about the upcoming Series with the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles; a fidgety, greasy-haired white man in an ill-fitting shirt and short, wide tie. All of them have come up Sixth Street from town, and that is the direction I am looking. It isn’t until I hear the sound of a bus approaching, with the whining downward shift of its gears, that I notice that someone has appeared next to me.

When I say “appeared,” I mean that quite literally. And I am momentarily bewildered by the fact that he doesn’t look as if he has finished appearing. Instead, the man next to me seems to have grown out of the sidewalk, with only his torso having emerged so far. He is hip-deep in the concrete and looks as though he has been there forever, waiting for a young King Arthur, me perhaps, to pull him free. He is a man; there is no doubting that, even though I am looking down at him. His hair is black and gray and mussed, wiry as a pot-scrubber, his nose wide and crooked, and there is a three- or four-day growth of salt and pepper beard on his face. Still, it isn’t until the bus comes to a stop in front of us and opens its doors that I understand what I am seeing—staring at, more precisely, in violation of every childhood admonition from my parents to do otherwise. The adults around me do no better, though. They all take an involuntary step backward, the young black woman pulling her child, and I am left standing alone with him.

“Thank you kindly,” the man says, as if everyone behind us has, in fact, remembered their manners. Then he winks at me. “You here all by yourself?”

“Yessir,” I reply, thinking I must be under some kind of spell to talk to a stranger and tell him I’m alone, a double-play of cardinal rules violations in the Graham household.

“You comin from the game?” He nods at my glove still clutching the ball.

“Yessir.”

“Lucky kid. What’s your name?”

“Henry.”

“Good baseball name. Like Hammerin Hank Aaron.” He cocks his head toward the bus. “Mind if I go first?”

“Nosir.”

“Thanks.”

He has no legs, barely even a hint of a thigh. Strapped over broad, powerful shoulders, he wears leather suspenders attached to a thick leather harness that protects the base of his perfectly flat torso. Even concealed inside a flannel shirt it is clear that his arms are massive, and he wears heavy work gloves on huge hands which he now places on the sidewalk in front of him. He presses, his shoulders shrugging downward, and in one smooth motion lifts his torso, swings it forward as if on a set of parallel bars, and sets it down again gently on the sidewalk. He does this two or three more times, all of us watching unabashedly, until he reaches the base of the bus steps. I feel the group around me tense, sure that the man has gone as far as he can go on his own, but equally unsure of how we are to help. He stops and looks up at the driver, who appears neither concerned nor surprised.

“Hey Russ,” the half-man says.

“How you been, John?”

“Fine thanks. Hey, what did the bus driver say to the legless man at the bus stop?”

“I don’t know. What?”

“‘Hey there. How you gettin on?’”

The driver shakes his head. “Come on now. I got other customers.”

“I’m comin,” he says. Then he places his hands firmly on the bottom step and lifts himself up as easily as I might have lifted myself out of a swimming pool. He takes the second step, then the third, then turns and swings himself down the aisle, out of sight.

“Come on folks,” the bus driver beckons, because none of us has moved, and I am the first to break the dazed tableau and follow John Kostka, The Swinger, up and into the bus for home.

Reprinted here courtesy of the author. For more information, visit www.philipbeard.net…