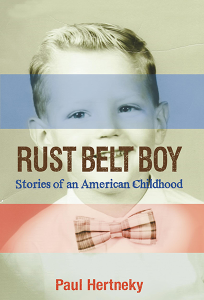

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share this excerpt from Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood, which publishes this week!

“Just like the mill towns of New England that preceded them, the steel towns of the Rust Belt have set loose a diaspora that spreads across the country. Rust Belt Boy portrays a moment in time: the last gasp of the industrial north where European immigrants had raised families and built communities and cities, but saw the end of their way of life looming on the horizon…”

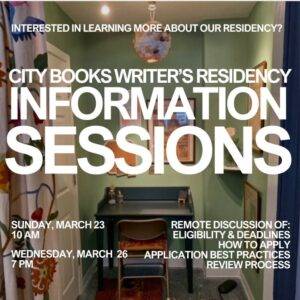

Hertnecky will be visiting Penguin Bookshop, City Books, Laughlin Memorial Library, and Sewickley Public Library later this month (May 21st-24th).

One Sunday before Mass, I followed my uncle Charlie into the crowded vestibule. As I waited to dip my fingers into the holy water, I noticed him cup his hands and splash the water onto his forehead.

One Sunday before Mass, I followed my uncle Charlie into the crowded vestibule. As I waited to dip my fingers into the holy water, I noticed him cup his hands and splash the water onto his forehead.

So that’s how he does it, I thought. That’s how he makes it look like he’s crying. It was a deliberate show of devotion, a bit of theater to accompany his loud singing and praying.

His parents had carried the infant Charles Blaise Cassidy across the Atlantic from Tralee on Ireland’s west coast to Pittsburgh, where he stayed. He never spoke about his family in Ireland. He related what his parents had told him about the crossing, and remembered only diesel fumes and the smell of the sea. But I often saw him standing at the kitchen sink, absentmindedly catching and caressing the stream running from the faucet.

Nephews and nieces sat entranced by stories he told of fighting fires in the city. I remember Uncle Charlie bowing and shaking his head as he recalled families who sat weeping on curbs, tears soaking their nightclothes as the flames reflected in their eyes. The hoses, he said, nearly pulled his arms from their sockets. With reverence and fear, the fireman with the middle name of Blaise, praised the water for saving the city and cursed it for the icy nights and the flooded basements in which family treasures were drowned.

Pittsburgh’s steel mills, working round the clock, kept the taverns open all night. When Charlie’s mates headed off to douse their own fires with boilermakers, he took the trolley straight home. And through all the family weddings and wakes, we never saw him drink a drop.

Yet he drank himself to death.

When his eldest son married and moved to New England, he invited Charlie to his house near the beach. At first Charlie refused to visit, saying he had no interest in the beach. But when his first granddaughter was born, Charlie relented and traveled to Massachusetts, where he would once again encounter the sea.

Charlie was struck to his knees before the blue eyes of his granddaughter and the waves as they crashed against the seawall and retreated to the depths. Throwing his freckled arms toward the Atlantic, he couldn’t bear to leave, as if the tide had seized him. He returned several times a year and always had to tear himself away, each time more painful than the last.

At home, he lined window sills and bookcases with shells and ordinary-looking rocks from the coast. He waxed about the mist and the kelp. And, even though he rarely swam and never set foot in a boat, if you got him started talking about the ocean, he blathered like an old salt on a barstool. My cousin and his wife had three more children, and Charlie visited more often. As much as the children, the sea itself drew him.

Finally, he couldn’t leave it behind.

Take into account his cock-eyed religious fervor, which leaned farther over the gunwales of his sanity as the years went on, convincing him that God had laid the Atlantic Ocean at his feet in a gesture of abundance. Charlie vowed to make it his own, to become one with it, to honor the Lord through gratitude.

He asked a buddy to steal two five-gallon carboys from the water coolers at city hall. And so the next time he and my aunt Dolores drove up to Massachusetts, Charlie loaded the empty bottles into the trunk of his car.

He waited until the last hours of their visit, then parked at the beach, waddled into the bay and allowed the surf to fill his bottles. He corked them, lugged them to the car, and turned his back on the ocean without regret this time, without so much as a glance in the rearview mirror.

Once home, he stashed the bottles in the closet near the front door. I had seen them one afternoon as I hung my coat, but couldn’t guess why they were there. Every morning for two years, as the sun broke through the clotheslines in the backyard, while he waited for the kettle to whistle, he padded over to the closet with a juice glass in his hand and decanted a few ounces of brine.

He bragged about his regimen one Sunday evening during my family’s regular visit. We had grown accustomed to Uncle Charlie retiring early on Sundays. When he was younger, he excused himself and went to bed. But as he grew older and more peculiar, he made a show of unfolding an old army cot in the living room and stretching out with the children as Disney’s Tinkerbell appeared on the TV screen.

Dressed in his pajamas, he stood before us and announced: “I have found the essence of life, of us all, of eternal health!” He raised a glass of brackish water from the Massachusetts Bay, that very bay surrounding Boston Harbor, its effluent ripened in a dark closet on Pittsburgh’s North Side. He praised God, his children, the earth and its waters and tossed it back. “Down the hatch,” he croaked, wiping his lips with the back of his hand.

We were aghast. Even I, an adventurous teenager and susceptible to any dare, could not imagine a wager high enough or a girl pretty enough to make me swallow the salty goo and tufts of algae I saw slide from the glass. Then Charles Blaise Cassidy lay down to sleep, all his blessings gathered around him and his faith taking him from within.

His wake was wet with reverence. But all I could think about were the legions of microbes, apparent in the green slime floating in his juice glass, attacking his organs, how water had delivered him to the new world, brought salvation to the victims he saved, called him home, and carried him away.

This excerpt is printed here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be repurposed without permission.