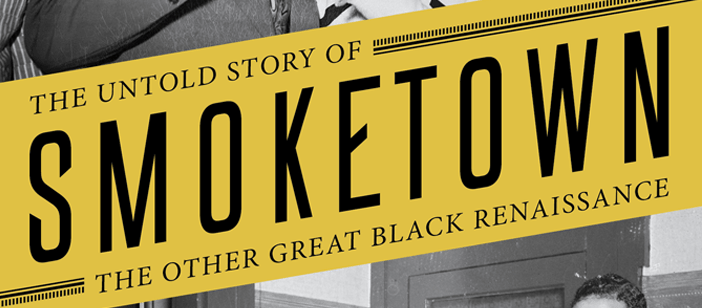

From the Publisher: “SMOKETOWN: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance by Mark Whitaker is the captivating story of the Renaissance of black culture, innovation, and glamour that burst forth in what may seem an unlikely place — Pittsburgh, PA — from the 1920s through the 1950s. Most people think of Harlem or Chicago as the homes to America’s historic black communities, but for a brief but glorious moment in the 20th century, one of the most vibrant and consequential communities of color in U.S. history emerged in Pittsburgh.

Drawing together the scattered existing record with extensive new reporting and research, Whitaker-a former managing editor of CNN, NBC News Washington bureau chief, editor of Newsweek, and author of the critically acclaimed memoir, My Long Trip Home-brings a glittering but forgotten world to life, telling the story of this town through the fascinating characters who forged it. Pittsburgh of this era was home to the country’s most widely read black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, which led the exodus of black voters from the Republican “Party of Lincoln” to the Democratic Party of FDR, changing this country’s political landscape forever. Pittsburgh gave rise to the two best Negro League baseball teams of all time (the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays), and introduced Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Some of the finest jazz musicians of the 20th Century, like Billy Strayhorn, Billy Eckstine, Earl Hines, Roy Eldridge, Mary Lou Williams and Erroll Garner came from Pittsburgh and were nurtured by the booming arts and culture scene during this Renaissance. One of our most influential black photographers, Teenie Harris, began as a photographer for The Pittsburgh Courier, and August Wilson himself, our greatest black playwright, was born and raised in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, an historic black neighborhood made all the more famous by Wilson’s plays, which are set there.

Whitaker is uniquely qualified to present this story. Whitaker’s grandfather was one of Pittsburgh’s first black undertakers, and his grandmother opened her own funeral parlor in the Hill District, which Whitaker wrote about in My Long Trip Home. His research into his own family’s history in Pittsburgh inspired this book.

SMOKETOWN is the first book to describe the extraordinary black community that emerged in Pittsburgh after the start of the 20th century. Whitaker’s expansive and masterfully told story of a vibrant community that thrived in demanding circumstances is a vital addition to the story of black America.”

Don’t miss out: Whitaker will be visiting Pittsburgh Arts and Lectures on February 21st!

“Mark Whitaker’s chronicle of the rise and fall of black Pittsburgh is a revelation on every page. Comprehensive in scope and skillfully written… [Whitaker] has recovered a major part of Pittsburgh’s – and America’s – history. Essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the world Teenie Harris captured in photos.” — Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

What inspired you to write about this period in Pittsburgh’s history?

What inspired you to write about this period in Pittsburgh’s history?

My father came from Pittsburgh, and I visited my grandparents and aunts and cousins there every year when I was a boy in the late 50’s and ’60s. But I knew little of the black community’s history before that period. Then in 2009, as I was doing research for my family memoir, I happened upon two photos of my grandparents in the Carnegie Museum of Art online archive of Pittsburgh Courier photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris. Clicking through the archive, I saw photo after photo of the most famous black cultural icons of the mid-20th century, all taken in Pittsburgh: Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn; Lena Horne and Ella Fitzgerald; Joe Louis and Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson. I began to realize what a crossroads of black history Pittsburgh had once been. And when I discovered that no one had written a narrative book capturing that full legacy, I decided that it was a story that deserved to be told.

You’ve written about Pittsburgh in your memoir, My Long Trip Home. What was new or surprising to you about Pittsburgh in your research for this book?

You’ve written about Pittsburgh in your memoir, My Long Trip Home. What was new or surprising to you about Pittsburgh in your research for this book?

I grew up hearing people talk about how extraordinary my father and his family were. Yet once I started working on the book, I saw that they were quite typical of Pittsburgh’s black community. While small in comparison with Harlem or Chicago’s South Side, it benefited from a unique confluence of historical forces. Like my grandmother’s parents, many of its black migrants came from the northern and eastern parts of the Old South. They had been house slaves or “free men of color,” and arrived with a high degree of literacy, musical training and religious discipline. They benefited from public schools that were both integrated and very well-funded, thanks to Pittsburgh’s Gilded Age philanthropists: colleges such as the Western University of Pennsylvania, now the University of Pittsburgh (where my aunt Cleo went); high schools such as Schenley High (my Grandmother Edith’s alma mater) and Westinghouse High (my father’s). The smell-or stench-of industry was also literally in the air in Pittsburgh, and it attracted blacks who dreamed of creating businesses. Among them were the pre-Civil War founders of barber shops and bathhouses that served as stops on the Underground Railroad; “Cap” Posey, a black steamboat engineer, shipbuilder and coal mine operator who was the richest black man in pre-World War I Pittsburgh; and my grandfather, C.S. Whitaker, Sr., who came from rural Texas and opened one of the city’s first black funeral homes.

You write about a variety of characters during this era in Pittsburgh. Did you have a favorite person to research and write about?

There were so many fascinating characters to bring to life in this story. Some grew up in Pittsburgh: jazz greats Billy Strayhorn, Billy Eckstine, Earl “Fatha” Hines, Mary Lou Williams, Erroll Garner, Ray Brown and Kenny “Klook” Clark; Negro League slugger Josh Gibson; artist Romare Bearden, and of course, playwright August Wilson. But it’s also amazing how many black icons of the 20th Century owed a big measure of their success to time spent in Pittsburgh or connections to its residents: musicians Lena Horne, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Sarah Vaughan; athletes Joe Louis, Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson; among others.

One of the most fun characters to learn and write about was Evelyn Cunningham, who reported for The Pittsburgh Courier in the late ’40s and ’50s. As a New Yorker, I knew that in her later years she was a grande dame of Harlem who was often photographed by The New York Times because she was such a fashion plate. But I didn’t know that Cunningham had started her career writing for the Women’s Department of the Courier in Pittsburgh. Around the newsroom, they called her “Big East,” because she was an almost six-foot tall redhead and had such a big personality, ready to arrange office parties with “the girls” and play poker with “the boys.” Bored with writing about weddings and garden parties, she lobbied the managing editor to send her to the South to cover the post-WWII spike in lynching. When he brushed her off, Cunningham seized on the story of a black man who had been killed for voting in Georgia, and spent a year reporting on the fate of his young widow and children and organizing a fund to build them a house in Florida. Cunningham charmed Thurgood Marshall and gained behind-the-scenes access to his school desegregation lawsuits before most other reporters. She spent six months in Montgomery, Alabama covering the 1956 bus boycott and published the first truly intimate profiles of Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta. Yet during most of this time, Cunningham was also writing a weekly sex and dating advice column for young black women in the Courier! She was a like a black female cross between intrepid early civil rights reporters like Claude Sitton and David Halberstam and Carrie Bradshaw of Sex and the City!

Tell us a little bit about Pittsburgh’s black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier. How did it have such a great impact on U.S. politics?

It’s another story of remarkable individuals, and one in particular. Robert Lee Vann, the only child of a former slave cook from North Carolina, came to Pittsburgh to get a law degree at Western University and was hired as publisher of the Courier when it was still a local pamphlet. Over the next three decades he transformed it into the most widely read and admired black newspaper in America, with 14 regional editions and a circulation that climbed close to a half a million by the end of World War II. Vann also had big political ambitions and used the Courier to wage dozens of crusades on national issues. In 1932, he became the most influential leader of the time to urge blacks, who voted Republican in memory of Abraham Lincoln, to defect to FDR’s Democratic Party-a political migration that transformed American politics and reverberates to this day. Vann also campaigned passionately on behalf of blacks in the U.S. military-a crusade that laid the groundwork for the role that black soldiers played in World War II and the desegregation of the armed forces by Harry Truman. After Vann’s untimely death in 1940 (one reason he is so little known today), his successors waged a “Double Victory” campaign to rally black support for the war in exchange for the promise of greater racial equality after it was over, and the betrayal of that promise helped light the fuse for the Civil Rights Movement.

Although the Pittsburgh Courier no longer exists today as it did then, are there any media outlets you see making waves and bringing change the way this paper did?

The Courier and other black newspapers fell on hard times in the 1960’s as white-run media started to cover the civil rights era and to hire away top reporters and editors. Today the Courier, The Chicago Defender and others exist almost entirely online, and have tiny readerships in comparison with their heydays. It’s sad, because while today’s white-owned outlets do cover “black issues,” they don’t celebrate black achievement and crusade for black causes in the way those publications did. Say what you will about that ethnocentrism, it helped foster a sense of pride and community across black America. And while some newer outlets try to carry on that tradition-Essence magazine; what’s left of Ebony and Jet; online publications like TheRoot, TheGrio, and TheUndefeated-none do it with quite the degree of ambition and attitude that the Courier exuded at its height.

What is the current status of the historic communities and institutions of black Pittsburgh that you write about in the book?

Not very good, sadly. As I describe at the end of the book, the bottom half of Pittsburgh’s most historic black neighborhood-the Hill District, the site of August Wilson’s plays-was torn down in the name of urban renewal in the 1950s. Then much of the Middle Hill was burned out in the riots that followed Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968. As black folks displaced from the Hill moved to surrounding neighborhoods, white folks moved out of those once mixed enclaves and the vicious cycle that has cursed so many black urban neighborhoods-post-industrial joblessness, declining schools, bank redlining and clashes with the criminal justice system-set in. In my reporting trips to Pittsburgh, I met terrific people trying to reverse that damage-school teachers and administrators; lawyers and judges; local politicians and activists-but it’s an uphill battle.

Pittsburgh is seeing a huge technology boom today and influx of young professionals looking for good jobs and a lower cost of living. What does this new renaissance mean, particularly for the black community in Pittsburgh?

Despite the still-distressing overall picture, there are small signs that Pittsburgh’s latest renaissance may be starting to benefit the city’s black population. Gentrification is beginning to reach the Upper Hill, the one part of that neighborhood that has remained more or less intact. (Denzel Washington’s film version of August Wilson’s “Fences” was shot there.) Tech giants like Google and Facebook and Uber that have set up shop in Pittsburgh to hire programmers and engineers from Carnegie Mellon and Pitt are making donations to schools in black neighborhoods. And for black students who can get into those universities, there is now a reason to stay in Pittsburgh once they graduate. Over time, they may help replenish the local black leadership class that was depleted when so many talented folks of the post-Smoketown era-people like my father-left Pittsburgh after high school and never moved back.