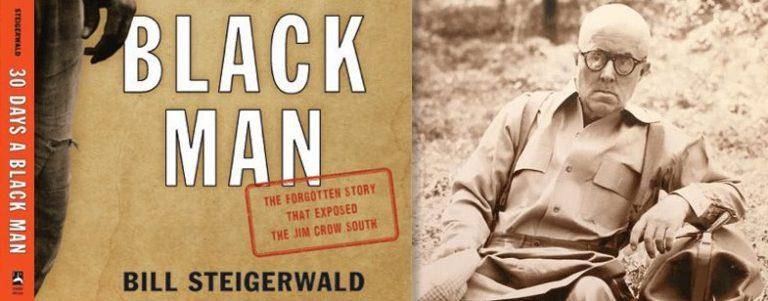

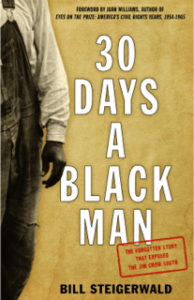

Bill Steigerwald is a veteran journalist from Pittsburgh who worked at the Los Angeles Times in the 1980s, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in the 1990s, and the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review in the 2000s. In 2013 he wrote and published Dogging Steinbeck, which exposed the many fictions and fibs John Steinbeck put into Travels With Charley.

We’re thrilled to be able to share the below excerpt from 30 Days a Black Man: The Forgotten Story That Exposed the Jim Crow South, Steigerwald’s “fascinating account of an anti-Jim Crow muckraking adventure” (Kirkus) featuring the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette‘s star reporter Ray Sprigle.

From the publisher: “In 1948 most white people in the North had no idea how unjust and unequal daily life was for the 10 million African Americans living in the South. But that suddenly changed after Ray Sprigle, a famous white journalist from Pittsburgh, went undercover and lived as a black man in the Jim Crow South.

Escorted through the South’s parallel black society by John Wesley Dobbs, a historic black civil rights pioneer from Atlanta, Sprigle met with sharecroppers, local black leaders, and families of lynching victims. He visited ramshackle black schools and slept at the homes of prosperous black farmers and doctors.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter’s series was syndicated coast to coast in white newspapers and carried into the South only by the Pittsburgh Courier, the country’s leading black paper. His vivid descriptions and undisguised outrage at “the iniquitous Jim Crow system” shocked the North, enraged the South, and ignited the first national debate in the media about ending America’s system of apartheid.

Author Bill Steigerwald elevates Sprigle’s groundbreaking exposé to its rightful place among the seminal events of the early Civil Rights movement.”

The two black men racing past the cotton fields in their 1947 Mercury were up to no good. Because their enormous dark green and chrome sedan attracted unwanted attention, they had to be cautious and alert as they crossed the Delta’s vast grid of dirt roads and cotton plantations. No one white knew who they were or why they were in Mississippi, and they had to work extra hard to hide their sophistication and curiosity. The night before they drove into the Delta, friends in Jackson had briefed them on tactics, strategy, and proper behavior, as if they were a pair of elderly saboteurs about to be dropped into Nazi-occupied France.

The two black men racing past the cotton fields in their 1947 Mercury were up to no good. Because their enormous dark green and chrome sedan attracted unwanted attention, they had to be cautious and alert as they crossed the Delta’s vast grid of dirt roads and cotton plantations. No one white knew who they were or why they were in Mississippi, and they had to work extra hard to hide their sophistication and curiosity. The night before they drove into the Delta, friends in Jackson had briefed them on tactics, strategy, and proper behavior, as if they were a pair of elderly saboteurs about to be dropped into Nazi-occupied France.

The men were warned not to stop and speak to sharecroppers working or walking along the roads. They were told never to argue with the “riders” who made up the armed mounted patrols that plantation owners used as field foremen and general overseers. They were also told not to talk too much in front of the white folks who held all the power and owned everything of value in the Delta. Above all, they were warned not to appear too interested in the dismal living conditions and suppressed civil rights of the huge black workforce that served “King Cotton.”

The men were warned not to stop and speak to sharecroppers working or walking along the roads. They were told never to argue with the “riders” who made up the armed mounted patrols that plantation owners used as field foremen and general overseers. They were also told not to talk too much in front of the white folks who held all the power and owned everything of value in the Delta. Above all, they were warned not to appear too interested in the dismal living conditions and suppressed civil rights of the huge black workforce that served “King Cotton.”

The men appeared to be just a couple of accidental travelers, two innocent old gents from the big city of Atlanta. They were nothing of the sort. The sixty-one-year-old in the passenger seat wearing the floppy checkered cap and heavy black-framed glasses was an imposter. He called himself James Rayel Crawford and carried a fake Social Security card in his wallet to prove it. But in actuality he was Ray Sprigle, a nationally famous newspaperman from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. He wasn’t a light-skinned black visiting from the North. He wasn’t even a black. He was 100 percent German-American white with a deep Florida tan, a spotless Republican voting record, and a 1938 Pulitzer Prize for proving a US Supreme Court justice was a member of the KKK.

The only genuine black man in the speeding Mercury was the lead- footed sixty-six-year-old driver, John Wesley Dobbs. Arguably the most influential black political and civic figure in Atlanta, he was a celebrated public speaker who had two cars and owned a handsome house in the wealthiest black neighborhood in America. Confident and driven, a flask of whiskey in his inside coat pocket, Dobbs could quote long poems and passages from Shakespeare from memory and often preached his favorite civil rights gospel that the only way for blacks to achieve full freedom and equality was through the three B’s—“Bucks, Ballots and Books.”

It was May 27, 1948. Ray Sprigle had come down into the Deep South to see—and feel— for himself how ten million black Americans lived under the system of legal segregation known as Jim Crow. For nearly three weeks he had been eating, sleeping, and living as a black man. Dobbs was his guide to the black world. Because he was the longtime grand master of Georgia’s Prince Hall Masons fraternal group, he was known and trusted by middle-class blacks across the South. In Atlanta and in the small towns of rural Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, Dobbs was introducing the undercover journalist to black doctors and undertakers, to sharecroppers, and to the families of lynching victims. When he told them Sprigle was gathering information for the NAACP, they believed it.

Dobbs was also Sprigle’s driver and protector. He knew how to com- fortably and safely travel the South’s dirt and clay back roads, where for black motorists the bathrooms were usually in the bushes and an “uppity” black man in a nice car could quickly find himself in serious trouble with white folks or the county sheriff.

Sprigle was a seasoned newsman. He had spent time in the Deep South before. He had covered the Blitz in London in 1940 during World War II, gone undercover into state mental hospitals, and witnessed a dozen death penalty electrocutions. He was not a civil rights crusader or a soft-hearted liberal, but what he was seeing made him ashamed to be an American. Now he and Dobbs were passing through the deepest, meanest, poorest part of the Jim Crow South, where decades of strict racial segregation and white supremacy had achieved a feudal level of oppression nearly a hundred years after the end of slavery. If the wrong people in the Delta found out they were on a secret mission for a Yankee newspaper and were in cahoots with the boss of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, it could cost them their lives.

In chronological order, these are photos of Pittsburgh Post-Gazette star reporter Ray Sprigle, his guide John Wesley Dobbs, plus photos of Walter White, Pittsburgh and Atlanta, the South and images of newspaper articles that carried Sprigle’s series:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3DEHEUtSzrU

This excerpt is printed here courtesy of the author and Lyons Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.