“These finely-crafted, moving novellas beckon us on through winding corridors of human consciousness and human hearts. In prose both lean and lyrical, Mark Saba offers intimate portraits of characters compelled to plumb the meanings of faith, loss, and the intensities of that extraordinary thing, an ordinary life. These meditative stories present us with time’s very texture, spiraling through events, moments, decades, in worlds of stark immediacy and chameleon mysteries. There’s love here, and sorrow, and the pleasures of the palpable, all made new by this perceptive writer’s artful words. Savor them. Plunge in.” —Jeanne Larsen, author of the Silk Road Trilogy

About the author: Mark Saba grew up in Pittsburgh and is the author of three works of fiction and three of poetry, most recently Ghost Tracks: Stories of Pittsburgh Past and the poetry collection Calling the Names. His work has appeared widely in literary magazines and anthologies around the U.S. and abroad. He is also a painter, and works as a medical illustrator and graphic designer at Yale University. Please see marksabawriter.com.

Hills blocked his view. They were everywhere: some full of old houses stacked like wooden blocks, others full of trees so green in summer he felt they were choking him. Hills marked every step of his, every ride in the car with his mother. He walked up and down hills to get to school, felt his throat drop as they drove down long hills to places where little creeks ran and branches lay in messy piles during the gray winter. To get anywhere, he had to see it in his head before they’d arrived. You could never see things approaching, because everything was hidden behind hills. And, if what he saw after he’d arrived was a little different than what he’d imagined in his head, the picture in his head was what stayed, what mattered.

Hills blocked his view. They were everywhere: some full of old houses stacked like wooden blocks, others full of trees so green in summer he felt they were choking him. Hills marked every step of his, every ride in the car with his mother. He walked up and down hills to get to school, felt his throat drop as they drove down long hills to places where little creeks ran and branches lay in messy piles during the gray winter. To get anywhere, he had to see it in his head before they’d arrived. You could never see things approaching, because everything was hidden behind hills. And, if what he saw after he’d arrived was a little different than what he’d imagined in his head, the picture in his head was what stayed, what mattered.

It had to do with the hills.

Often they would go visiting. Sometimes they would take the noisy streetcar, and sometimes they would ride in the little blue car. The little blue car took them to more mysterious places, places that had nothing to do with his memory, or what he saw in his head. Those were the most interesting places to visit.

He did not know it at the time, but some of these places he would visit only once, once in his life. Then they would vanish, just as if he had never been there, or as if he had only been there in his head. As he grew older he had trouble separating the things he had seen just once from the things he had seen only in his head. He could never be sure, for how could he have imagined anything, were it not for what he actually saw?

There was once a trip to visit a woman his mother knew, a woman she didn’t see very often, if ever. They drove through and around the hills. They left the city with its red and orange brick roads, its bumps and breath-taking spills when the roads dipped. It was a breezy day. His sister was at school—another mysterious place that held some kid of magic, a magic adults spoke of with reverence. After turning another bend, his mind lost in the tops of trees, they drove up a small hill that was a parking lot. On either side, connected buildings fell down the hill like big steps. They had brown roofs that sloped down onto the buildings like upside-down, open boxes.

Inside there lived a woman with a clear voice and short, dark hair. She and his mother hugged and kissed, and told him the woman was a friend of his aunt who had died, his mother’s sister. Then they did the usual visiting thing: sat down at the kitchen table to drink coffee and talk.

The mention of his dead aunt’s name—Celine—made his face go blank. Luke, his mother said. Luke. Here, Dolly has something for you. A toy. A dented metal, swirling top. He pumped the handle up and down and the top swirled, its yellows, reds, and blues all coming together into a swirling cloud as he thought of his Aunt Celine.

He was still in love with her. He saw her coming down the stairs in a dark dress that moved when she walked. She was excited, smiling, holding something she wanted to give him. Her smile made her black eyes light up: her wavy dark hair shining against her shadowy skin. She handed him the gift.

She handed him the gift.

She handed him the gift.

He ripped open the paper and she helped him open the white box. Inside it were pajamas that looked like alligator skin. For him! He looked at her stooping beside him with her smile, her smiling black eyes. He was in love with her. Then she was gone.

He had no sense of how or why she had left. All that remained of her was the box with the alligator pajamas.

Now she was back. She had a friend, a woman with short dark hair and a loud voice who had mentioned her name. Where do the people you love go? Do they always stay inside your head, so that you see them over and over?

Sometimes he went into the books they read. The Owl and the Pussycat, a big book with a green cover and big pictures inside of the two of them riding together in a pea-green boat. How calm the water was under moonlight. When he was in that book he couldn’t feel anything else, just the nice boat and all the colors from the book floating around him like jewels. Later he would make friends with the Hardy Boys, exploring caves with them, solving mysteries, spying strange neighbors.

He picked up most of these books from the library, a small library in a yellow-brick building that sat across the street from his doctor, whom they went to see every week.

Dr. Stendhal was a cruel, smelly man. He smelled like the absence of everything: the absence of warmth and comfort, the absence of good food, the absence of fun, the absence of what he imagined to be a father. And to top it off, he showed absolutely no expression while torturing Luke with his needles and cold metal instruments.

Illness was something Luke didn’t really mind though, because it made him feel a little special. The nuns at school sent home tidy little packets of work for him to do, and he completed these tasks with ease. He was sick more often in the winter. That’s when he couldn’t breathe, when coughing fits kept him up most of the night. His mother said Dr. Stendhal’s shots would help him, which was the only reason he suffered them. The long drive down to his office, along the busiest road he knew, passing foreign city neighborhoods while catching glimpses of more distant neighborhoods among the hills, had a calming effect on him and his coughing. There was so much to see, and so much to think about. What went on in all those oddly-shaped buildings? Who lived in all those big old houses with the wide front porches? Who was buried in those sloping green cemeteries? And most importantly, how did firemen manage to shove their wonderful red, yellow, and white trucks into those little garages? He knew that, when they went to see Dr. Stendhal, other kids were at school, which meant that only he could see all that went on in the world while his classmates were imprisoned.

That was magic.

How could he not feel that he was somewhat different? It was not only because of his illness and the fact that his father was dead, but because he felt the world flipped its mesmerizing pages, it seemed, for only him to see. Every night, following his prayers and his mother’s kiss, he saw those pages flipping endlessly in his head. It didn’t matter whether they showed good or bad things, whether they made him smile or shudder: there they were, every night, just like one of the many books he read. Only better, because he didn’t have to read them. They read themselves to him.

During his wakeful hours he saw them too, and of course they competed with the new things he was seeing and hearing, so that the present and past were always colliding in his head. Luke, Sister DeLellis would say. And he would look up and give the answer. She never knew that he was living in two worlds at once. It was so easy to do—why did she look surprised?

The world of adults was many worlds too. Each adult brought a different world to him: different feelings, different smells, different words, even different colors. There was Mrs. Fisher, the neighbor who lived in a dark brown house with an overgrown, brown yard. Luke had never seen her, but it was widely known among neighborhood kids that she was a witch. No matter what kind of day it was—even the most beautiful start of summer vacation in June—dark trees shrouded her house. Most often he ran by it.

Sometimes adults were like ships approaching in open water; he didn’t know if he would survive them. But most often (except for Dr. Stendhal) he did. Visitors from his mother’s very large family included great aunts dressed in flowers, great uncles red-faced and smelling of beer, cousins who were allowed to have dogs, and most lovingly, his only grandfather.

Grandfathers are another kind of father. In fact, they are fathers themselves. They could be the father of your father. But Luke had no father, and his father’s family (he had heard of them) occupied only a distant corner of his mind. It was his mother’s father, then, who embodied all he knew of that word.

His grandfather’s world was the earth. His skin was dark like the earth. His eyes were the color of twigs. Once, while they were sitting on the front porch one late-summer evening, a hummingbird flew by them, then hovered over the zinnia patch at the base of the steps. Luke was amazed, speechless and ecstatic. But his grandfather only showed a little smile, saying, He’s going to fly all the way to Mexico for the winter. So there they were, connected by a little bird to exotic Mexico, the same Mexico that had fashioned his grandfather’s cane, a whittled stick that was brightly painted with animals. How had he gotten it?

On Sunday nights, after one of his grandmother’s long dinners and maybe a game of kickball in the street with the neighborhood kids, he and his grandfather would watch a nature show together. An oddly quiet old man with a thin gray mustache would announce what they were going to see: gazelles, lions, buffalo, elk? Termites, honey bees, eagles, wolves? Other times they would watch the channel where men went fishing, where they caught fish bigger than Luke, hanging by their gills from the fisherman’s hands.

Beginning in early spring they would descend the long stairs to the concrete basement, where his grandmother did laundry, where a rack in the middle of the floor stretched out her zig-zaggy afghans, where his mother’s cousin (who lived on the second floor) brewed beer, and where his grandfather kept a whole big family of ceramic pots, peat pots, fertilizers, watering cans, and seed packets. Luke smelled the early lives of vegetables and flowers there. He smelled the whole world there, and everything it grew, by the magic of his grandfather’s, and his own, hands. Together they planted seeds, mixed strange concoctions of manures, kept notebooks to track their successes and failures. In the end, as summer approached, they carted all the plants outdoors, where Luke, under careful supervision, became his grandfather’s hands. He transplanted tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, broccoli, and cabbage. And earlier, when the air was still cool and the ground just started to give way, he planted seeds directly into the ground: lettuce, peas, radishes, beets, onion sets, and even potato spuds. Their garden, which sat directly behind the garage, found protection by tall hedges on two sides. In the next yard the Stambroskis grew grapes.

There were other worlds, other adults whose lives intersected with Luke’s: the man who raised tropical fish and sold them to him for 5¢ each, the man who spoke another language and raised pigeons in a hillside backyard-full of cages which he let out to fly around the city and return, the neighbor who raised canaries, the neighbor who raised plums and cherries, and the grandmother who ran the little store at the top of the hill and dropped penny candy into a little bag for him to fish through during the long walk back down to his grandparents’ house.

Each of these souls froze in Luke’s imagination. Often he called them up to think about them, about how their lives were so different, about how many lives were even possible in the world, each one making up its own. Together they all seemed to fit together, though. As if Luke were walking through a storybook. All the pages were there: the ones he couldn’t stop seeing at night.

At night he heard a train passing through the hills, out of sight, its long whistle finding its way up through the woodland hollow, then up the hill of his backyard, through the window, to his ears. It was often his lullaby, something he wished would never go away.

When he was a bit older he and his best friend, Jerry, investigated that hollow, plumbed its secrets, walked along the creek for hours until they felt sufficiently lost on their excursion. They caught crayfish and salamanders along the way, outran vicious dogs, hacked through elephant ears nearly as tall as themselves, swung on hanging vines, and kept an eye out for poison ivy, which lurked everywhere. If the Willow Street boys wanted to come along, they shunned them, preferring to keep this adventure to themselves. It was a grand thing for a couple of ten-year-olds. Perhaps they would find the infamous Indian Falls along the way, which some of the older neighborhood kids had mentioned in passing. They longed to see the rusty red water that fell there. There might even be arrowheads lying about.

Once they ventured too far, far beyond where the hollow emptied out. They took a turn up a farmer’s bare hillside, through a small grove of trees, and saw a tiny wooden house in the distance. Two grown collies ran out to meet them, barking but wagging their furry tails. Luke and Jerry froze. They won’t hurt yins, said an old voice in the distance. The boys looked up and spied her rocking on her wooden slab of front porch.

Bertha, as she was named, cheerfully called the boys over through her many missing teeth. She asked them if they liked the dogs, and said the two collies didn’t always get along. Would the boys like to take one home with them? It would be okay to go home and ask their mothers and then come back later for it.

Luke put his arms around the lighter dog—a nice, tan color—and felt its coarse fur give way to warmth and a distant heartbeat.

NO! said his mother, and he knew there would be no use in pleading. The doctor said no pets. And I don’t want to clean up after it.

But I can help…

No!

That was the end of Bertha and her two beautiful collies.

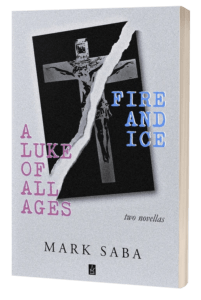

A Luke of All Ages and Fire and Ice: Two Novellas by Mark Saba are copyright © 2020 Mark Saba. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.