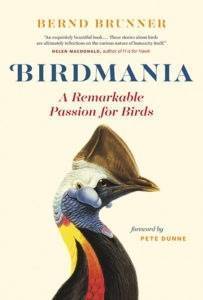

Bernd Brunner is an acclaimed writer whose books have been translated into a variety of languages. His work has been published in Lapham’s Quarterly, the Paris Review, the Wall Street Journal Speakeasy, and the Huffington Post, and he has lectured at New York’s Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts and Culture, the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley, and the Goethe Institute in San Francisco.

Don’t miss out: Bernd Brunner is giving a presentation about the book on November 18 at the Carnegie Museum for Natural History through Pittsburgh Arts & Letters.

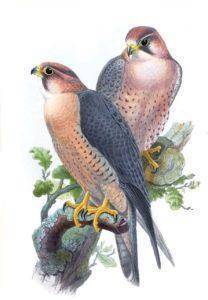

From the publisher: “There is no denying that many people are crazy for birds. Packed with intriguing facts and exquisite and rare artwork, Birdmania showcases an eclectic and fascinating selection of bird devotees who would do anything for their feathered friends.

In addition to well-known enthusiasts such as Aristotle, Charles Darwin, and Helen Macdonald, Brunner introduces readers to Karl Russ, the pioneer of ‘bird rooms,’ who had difficulty renting lodgings when landlords realized who he was; George Lupton, a wealthy Yorkshire lawyer, who commissioned the theft of uniquely patterned eggs every year for twenty years from the same unfortunate female guillemot who never had a chance to raise a chick; George Archibald, who performed mating dances for an endangered whooping crane called Tex to encourage her to lay; and Mervyn Shorthouse, who posed as a wheelchair-bound invalid to steal an estimated ten thousand eggs from the Natural History Museum at Tring.”

“An exquisitely beautiful book …These stories about birds are ultimately reflections on the curious nature of humanity itself” — Helen Macdonald, author of H is for Hawk

From “In the Company of Birds”

There were, and still are, people who seek the company of birds for years, decades, or even most of their lives without thinking there is anything odd about their behavior. Robert Stroud (1890–1963) pursued his hobby in a highly unusual environment: a prison cell. After he killed a rival in a dispute over his girlfriend, whom he supposedly pimped as a prostitute, he spent more than half a century in various penitentiaries in the United States. While he was in a federal maximum security prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, he started breeding canaries—about three hundred of them. He studied their behavior and physiology, developed a handful of cures for bird diseases, and wrote a couple of books that earned him the respect of the ornithological community. He is said to have become interested in birds after finding an injured sparrow in the prison courtyard. Unfortunately, he allowed his canaries to range freely in his prison cell, which led to serious hygiene problems. When prison authorities ordered an end to his activities, an acquaintance (who later became his wife) campaigned on his behalf and collected fifty thousand signatures on a petition that turned the tide in his favor: not only was Stroud allowed to continue breeding canaries, he even got a second cell for his program. The discovery that he was using some of his equipment to brew alcohol was the final straw for the authorities in Kansas, and he was transferred to Alcatraz. Oddly enough, he went down in history as the “Birdman of Alcatraz,” even though he was no longer given the resources to breed birds after his transfer. In fact, he was expressly forbidden to pursue his avocation.

There were, and still are, people who seek the company of birds for years, decades, or even most of their lives without thinking there is anything odd about their behavior. Robert Stroud (1890–1963) pursued his hobby in a highly unusual environment: a prison cell. After he killed a rival in a dispute over his girlfriend, whom he supposedly pimped as a prostitute, he spent more than half a century in various penitentiaries in the United States. While he was in a federal maximum security prison in Leavenworth, Kansas, he started breeding canaries—about three hundred of them. He studied their behavior and physiology, developed a handful of cures for bird diseases, and wrote a couple of books that earned him the respect of the ornithological community. He is said to have become interested in birds after finding an injured sparrow in the prison courtyard. Unfortunately, he allowed his canaries to range freely in his prison cell, which led to serious hygiene problems. When prison authorities ordered an end to his activities, an acquaintance (who later became his wife) campaigned on his behalf and collected fifty thousand signatures on a petition that turned the tide in his favor: not only was Stroud allowed to continue breeding canaries, he even got a second cell for his program. The discovery that he was using some of his equipment to brew alcohol was the final straw for the authorities in Kansas, and he was transferred to Alcatraz. Oddly enough, he went down in history as the “Birdman of Alcatraz,” even though he was no longer given the resources to breed birds after his transfer. In fact, he was expressly forbidden to pursue his avocation.

That was not the end of the story, however, for the young Delacour soon developed an interest in exotic birds: Asiatic pheasants, various guinea fowl found in different parts of Africa, and miniature chickens called bantams.

Over the years, Delacour constructed several birdhouses on the family estate, built an enclosure especially for ostriches, and had a large pond installed in front of his house, where ducks and swans soon moved in. Now he could observe the activity of wild birds directly from his window, and he was entertained by birdsong until late into the night. A large, heated birdhouse comprising forty-seven aviaries followed. It was a miniature paradise.

The cages could not be seen from the outside; you opened a door near the end of a long wall, screened by trees and shrubs, and suddenly you found yourself surrounded by birds. You walked along straight paths, all lined with flowers; each compartment was a little garden in which gorgeous birds showed to full advantage. The cages were varied in shape and size; here and there, other paths began, affording new vistas. At a turn one entered the indoor gallery, with its rows of cages, and it looked like a library of birds, showing among tropical plants. Even in these early years one could see there hummingbirds, sunbirds, and birds of paradise, then very unusual.

Toward the end of World War I, the garden at Villers was destroyed, but Delacour soon purchased the Château de Clères in Normandy and quickly set about adapting the garden and grounds for his birds and other animals. Later, he proudly claimed that up until 1940, there was probably no other place in the world where so many rare species were gathered together as there were in the gardens at Clères. There were three thousand birds, belonging to more than five hundred species, most of which he had collected during expeditions to India, Indochina, China, Japan, Madagascar, and the Caribbean. He carefully chose birds that would not damage plants in the garden and specifically avoided birds of prey and fish-eating waterfowl. Despite these restrictions, he had more than one hundred species of waterfowl alone. Clères became an attraction for nature lovers from all four corners of the world until, in 1940, thirty-two bombs from the German air force inflicted severe damage on life in the park. Delacour immigrated to the United States, became an American citizen, worked in the Los Angeles County Museum, and, like the old-school citizen of the world that he was, commuted back and forth between the United States and Europe for many years. In 1947, the park at Clères was reopened to the public. It exists to this day.

Excerpted from Birdmania: A Remarkable Passion for Birds by Bernd Brunner. Published October 24, 2017 by Greystone Books. Condensed and reproduced with permission from the publisher.