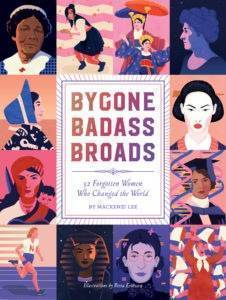

From the Publisher: “Based on Mackenzi Lee’s popular weekly Twitter series of the same name, Bygone Badass Broads features 52 remarkable and forgotten trailblazing women from all over the world. With tales of heroism and cunning, in-depth bios and witty storytelling, Bygone Badass Broads gives new life to these historic female pioneers. Starting in the fifth century BC and continuing to the present, the book takes a closer look at bold and inspiring women who dared to step outside the traditional gender roles of their time. Coupled with riveting illustrations and Lee’s humorous and conversational storytelling style, this book is an outright celebration of the badass women who paved the way for the rest of us…”

Don’t miss out: Lee will be visiting White Whale Bookstore on March 20th!

About the Author: Mackenzi Lee holds a BA in history and an MFA in writing for children and young adults from Simmons College. She is the New York Times bestselling author of the historical fantasy novels This Monstrous Thing and The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue, as well as the forthcoming The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy (2018) and Semper Augustus (2019). She currently calls Boston home, where she works as an independent bookstore manager.

Empress Xi Ling Shi

Empress Xi Ling Shi

2700-ish BCE, China

The Legendary Inventor of Silk

The story of Empress Xi Ling Shi is so wrapped up in legend it’s hard to know what’s real and what’s mythology. But no matter how much of her story is true in the strictest sense of the word, she’s an important figure in Chinese history.

Also, “wrapped up” is a really great pun.

Keep reading — you’ll get it in a minute.

Keep reading — you’ll get it in a minute.

Xi Ling Shi, also known as Xilingshi, Lei Tsu, or Leizu, was the teenage bride of Emperor Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, who boasted an impressive resume that included founding the religion of Taoism, creating Chinese writing, and inventing the compass and the pottery wheel. Emperor Huangdi ruled China between 2697 and 2597 BCE, when cloth manufacturing was still a new and confusing process and the silk that put China on the international trade maps had not yet been discovered.

Until Empress Xi Ling Shi.

The story goes that the empress was sitting in her garden, drinking a cup of tea, when a cocooned bug dropped into her cup from the branches of the mulberry tree hanging over her. Defying feminine stereotypes, the Empress did not freak out over the bug — instead, she fished it out of her tea and examined it. The heat of the tea had begun to separate the filament of the cocoon, and Xi Ling Shi began to unravel it.

From that one small cocoon came yards and yards and yards of bright, strong filament, encasing one of the tiny worms that had been making an all-you-can-eat buffet out of the leaves of the mulberry trees in the royal garden.

That was when she had a thought.

Xi Ling Shi approached her Emperor husband and asked him if he would indulge a crazy idea she had: Instead of getting rid of the worms that had been ravaging their mulberry trees, she wanted to plant more trees for these worms to chow down on, then unfurl their little cocoons and make cloth from those fine fibers. Being an innovator himself, the emperor was super on board.

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut

c. 1508-1458 BCE, Egypt

Egypt’s First Female Pharaoh

Hatshepsut didn’t need a military coup, violent revolution, or backdoor assassination to ascend to the throne of Ancient Egypt, and she didn’t need any of those things to hold onto it either. All it took was a little brains, a little talent, and a lot of being in the right place at the right time.

Hatshepsut was born into the ruling family of Egypt but was never slated to be the one in charge. When her father, Pharaoh Thutmose I, died suddenly, Hatshepsut’s half-brother/husband Thutmose II (don’t think about it too hard-inbreeding was a common way to make sure the crown stayed in the family in Ancient Egypt) took the throne and made Hatshepsut his queen. But Thutmose II died young, and his official heir — Hatshepsut’s infant stepson and Thutmose’s son by another woman — was too young to govern.

A woman had never ruled Egypt before, but Hatshepsut executed ye old power grab before you could say “nonmilitant takeover,” installing herself upon the throne until the baby pharaoh was “old enough” to rule (in quotes, because Hatshepsut had no intention of giving up the pharaoh-ship once she got her hands on it).

She was Egypt’s first female pharaoh, and her reign would last for twenty-two brilliant years.

As a woman in the ultimate position of power, Hatshepsut had her work cut out for her in establishing the legitimacy of her claim. Image is everything for a politician, so she immediately commissioned multiple statues of herself as Pharaoh, many of which depict her with a beard, at her request, likely as a way of showing that she had just as much authority and right to rule as any man. Then, to stay popular with the people, she undertook an enormous HGTV-style renovation of Egypt, commissioning dozens of ambitious building projects around the Nile. The most impressive was the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri in Thebes, as well as a ten-story obelisk dedicated to her accomplishments and inscribed with the very modest statement, “I have always been king.”

Hatshepsut’s rule was a time of peace and prosperity, which she used to expand trade routes and diplomacy with Egypt’s neighbors. She established a friendly relationship with Punt, a neighboring region on the northeast coast of Africa, and began prosperous trade between the two nations. Trade with Punt included importing valuable goods like myrrh, which you might know as one of Jesus’s birthday presents.

After two decades of aggressively successful ruling, Hatshepsut died in what would have been her forties. Her stepson, Thutmose III, the former-baby heir apparent in whose stead she had been ruling, took the throne after her death. He was not as into Hatshepsut’s kickass accomplishments as everyone else was and ordered her monuments defaced, statues of her pulled down, and records of her scrubbed from Egyptian history. He took all credit for her accomplishments, and history almost forgot about Hatshepsut entirely. Egyptologists didn’t know she existed until 1822, when they were able to decode the hieroglyphics on the walls of Deir el-Bahri, near where she was buried.

In 1903, the British archeologist Howard Carter discovered Hatshepsut’s sarcophagus, but it was empty (most of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings, where she was buried, were). After almost a century of searching, her mummy was recovered in 2007. It is now on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Excerpted from Bygone Badass Broads by Mackenzi Lee and illustrated by Petra Eriksson. Copyright © 2018. Excerpted by permission of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.