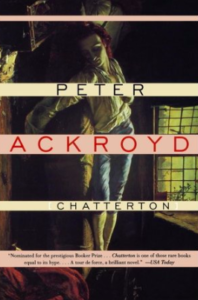

Quantum Theatre’s latest production, Chatterton, is adapted from Peter Ackroyd’s bestselling and Booker Prize-nominated novel of the same name, a century-spanning exploration of authenticity and literary counterfeiture (“one of those rare books equal to its hype… a tour de force, a brilliant novel” – USA Today).

To celebrate Chatterton, Quantum Theatre is hosting an online book club (and two in-person events) to discuss Peter Ackroyd’s novel, which you can start reading right here on Littsburgh!

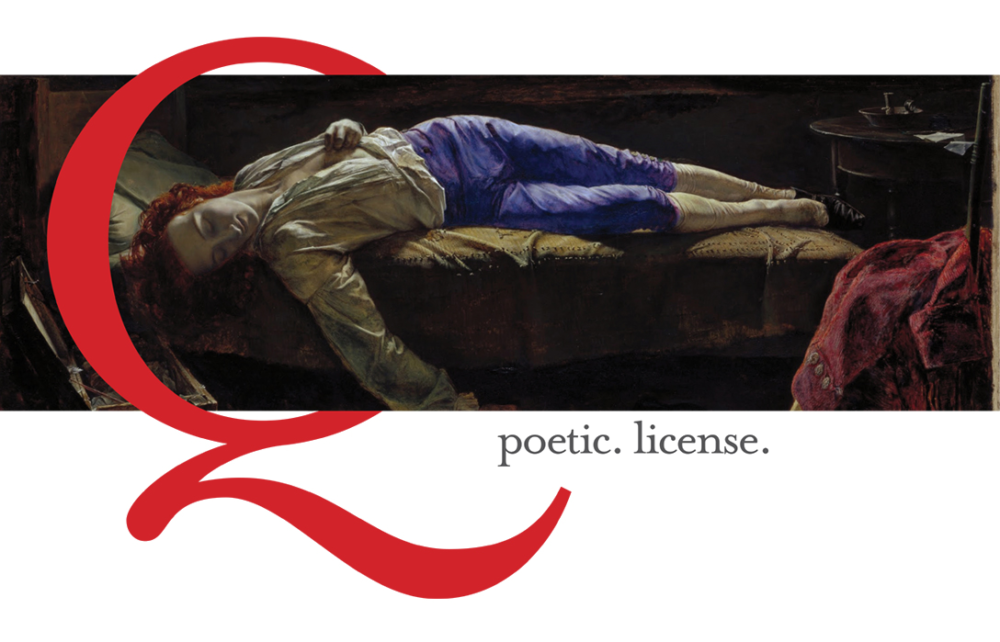

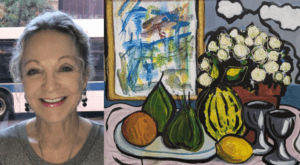

Quantum Theatre’s Chatterton spreads out in three dimensions, immersing its mobile audiences in the haunting spaces of Trinity Cathedral Pittsburgh. Its plot takes inspiration from the historical character Thomas Chatterton: the Romantic era’s most famous suicide, an 18th century poet who took his young life and was immortalized 100 years later by a very famous painting. Modeling for that painting was Victorian poet George Meredith, whose own dramatic life also features in Ackroyd’s novel. Meanwhile, in the present, poet Charles Wychwood goes on a hunt to solve mysterious puzzles from the past – is what we believe about Thomas Chatterton truth or fiction?

Chatterton offers a trifecta of poets in three centuries, a colorful London with Dickensian characters bristling with humor, and deep debates on what’s real and what’s fake in the intertwining worlds of art and commerce…

Chatterton will run for seven weeks, from September 14 – October 28. For more information about the performance, and on the Chatterton book club, check out our spotlight on Quantum Theatre!

‘Come,’ he said. ‘Let us take a walk into the meadow. I have got the cleverest thing for you that ever was. It is worth half a crown merely to have me read it to you.’

‘Come,’ he said. ‘Let us take a walk into the meadow. I have got the cleverest thing for you that ever was. It is worth half a crown merely to have me read it to you.’

He waved the little book at her, but his eager manner frightened the girl and she walked away from him quickly. Then, taking courage from the sight of a friend sitting on the church steps, she called out to him over her shoulder, ‘What a poor boy you are, to be sure. And Lord, Tom, how your shoes gape open!’

‘I am not so poor that I need pity from such as you!’ Chatterton ran out into the open fields, pushing his face against the wind that chilled him; then he stopped short, sat down on the cropped grass and, gazing at the tower of St Mary Redcliffe, muttered the words that had so powerfully swayed him:

The time of my departure is approaching.

Nigh is the hurricane that will scatter my leaves.

Tomorrow, perhaps, the wanderer will appear –

His eye will search for me round every spot,

And will, – and will not find me.

He looked at the church and, with a shout, raised his arms above his head.

‘Yes, I am a model poet,’ Meredith was saying. ‘I am pretending to be someone else.’

‘Yes, I am a model poet,’ Meredith was saying. ‘I am pretending to be someone else.’Wallis put up his hand and stopped him. ‘Now the light is right, now it is falling across your face. Put you head back. So.’ He twisted his own head to show him the movement he needed. ‘No. You are still lying as if you were preparing for sleep. Allow yourself the luxury of death. Go on.’

Meredith closed his eyes and flung his head against the pillow. ‘I can endure death. It is the representation of death I cannot bear.’

‘You will be immortalised.’

‘No doubt. But will it be Meredith or will it be Chatterton? I merely want to know.’

Harriet Scrope rose from her chair, eager to deliver her news. ‘Cut is the bough,’ she said, ‘that might have grown full straight.’ And she doubled up, as if she were about to be sawn in half.

‘Branch.’ Sarah Tilt was very deliberate.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘It was a branch, dear, not a bough. If you were quoting.’

Harriet stood upright. ‘Don’t you think I know?’ She paused before starting up again. ‘We

poets in our youth begin in gladness. But thereof in the end come despondency and madness.’ She stuck her tongue out of the side of her mouth and rolled her eyes. Then she sat down again. ‘Of course I know it’s a quotation. I’ve given my life to English literature.’

Sarah was still very cool. ‘It’s a pity, then, that you didn’t get anything in return.’ And they both laughed.

Charles Wychwood sat with his head bowed. He watched the leaves falling to the ground; they were rustling together and he heard, also, the sound of hammers, of drilling, of workmen calling to each other inside the new building. Then the pain returned and it was only later that he noticed how the leaves had been swept away, the noises stopped. There was a young man standing beside him, gazing at him intently: he put his hand upon Charles’s arm as if he were restraining him. ‘And so you are sick,’ one said. And the other replied, ‘I know that I am’. Charles looked down again in despair and, when he glanced up, the figure of Thomas Chatterton had disappeared.

Extract from Chatterton by Peter Ackroyd, © Peter Ackroyd 1987. Reproduced by permission of Sheil Land Associates Ltd.

For tickets and showtimes, visit QuantumTheatre.com.

For the Chatterton book club, visit Quantum Theatre’s Facebook group.