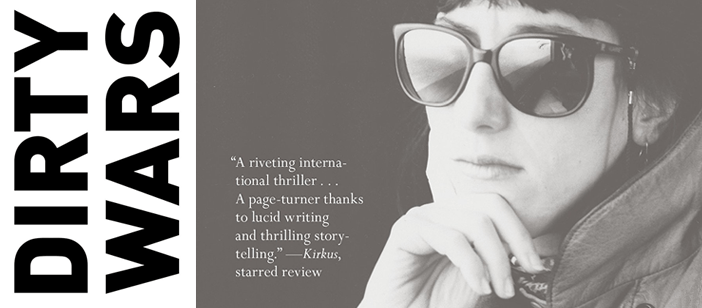

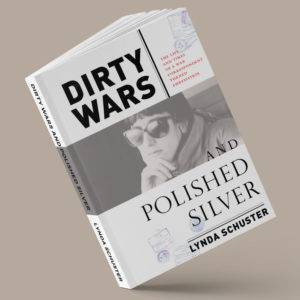

Lynda Schuster is a former foreign correspondent for The Wall Street Journal and The Christian Science Monitor who has reported from Central and South America, Mexico, the Middle East, and Africa. Her writing has appeared in Granta, Utne Reader, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New York Times Magazine, among others. She lives in Pittsburgh with her husband and daughter.

From the Publisher: “Dirty Wars and Polished Silver is Schuster’s story of her life abroad as a foreign correspondent in war-torn countries, and, later, as the wife of a U.S. Ambassador. It chronicles her time working on a kibbutz in Israel, reporting on uprisings in Central America and a financial crisis in Mexico, dodging rocket fire in Lebanon, and grieving the loss of her first husband, a fellow reporter, who was killed only ten months after their wedding.

Equal parts gripping and charming, Dirty Wars and Polished Silver is a story about one woman’s quest for self-discovery—only to find herself, unexpectedly, more or less back where she started: wiser, saner, more resolved. And with all her limbs intact.”

Don’t miss out: Schuster will be visiting Rodef Shalom Congregation for their new reading series (“A Conversation with the Author”) on Thursday, November 16th!

The kibbutz is echo-quiet; no one works on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. The little paths that crisscross the settlement, usually filled with people walking or riding bicycles or pushing carts stuffed with small, communally raised children, are deserted. Even the running radio chatter that seeps out from buildings with the hourly beeping time signal is silent. The Voice of Israel goes dead for the day.

The kibbutz is echo-quiet; no one works on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. The little paths that crisscross the settlement, usually filled with people walking or riding bicycles or pushing carts stuffed with small, communally raised children, are deserted. Even the running radio chatter that seeps out from buildings with the hourly beeping time signal is silent. The Voice of Israel goes dead for the day.

There’s air conditioning in the recreation room. A couple of my comrades from the ulpan sprawl on a sofa. In the distance, the Golan’s usually craggy profile is barely visible behind the quivering mask of heat. Michael, my newly minted boyfriend from the British group, shuffles in: black curls and emerald cat-slitted eyes, topped with an antic sense of humor.

Michael says, “I was wondering where you got to.”

“I’m trying not to think about food,” I say.

He reaches across me to grab an outdated copy of Time, but never gets there—the air around us is suddenly exploding. “Bloody hell!” he says. “What was that?”

More eardrum-shredding detonations in rapid succession shake the ground. We’re all standing now, staring stupidly out the picture window at smoke billowing from the Golan Heights. “Maybe an earthquake?” one of the other students suggests.

Michael says, “Don’t be an idiot.”

There’s commotion outside; someone shouts at us to run to the bomb shelters. I have no idea where to go. We follow a kibbutz member to a clearing, my heart a little tom-tom in my chest, then down leaf-strewn steps to a door. He tugs on it. Locked.

Michael and I take off at a sprint for Simcha’s house, dog-cringing at each explosion. She’s standing in her garden with some neighbors.

I say, “What’s happened?”

“We’re under attack,” she says. “The Syrians crossed the border and are bombing the Golan. The Egyptians crossed into Sinai.”

“How do you know?”

“The Voice of Israel came back on the air. The chief rabbis said we’re at war and that it’s okay to break your fast now and not wait until sunset.”

“What should we do?”

“Go back to your building.”

We follow her advice, but no one in charge is around. Michael retrieves a radio from his room; we hear the urgent codes being broadcast on the army channel that call up people to reserve duty. The attacks have taken the country completely by surprise. The kibbutz, too; the place is suddenly swarming with men half-dressed in military uniforms, guns slung over their shoulders, gear falling out of hastily packed duffel bags. This does not inspire confidence. If I’m going to die, I think, heading to the dining hall, at least now I won’t die hungry.

A woman in charge of the kitchen is dishing out pieces of chicken left over from the previous night. Gnawing on a drumstick, I jog back to Simcha’s. She’s gone. Michael and I feel our way in the dark to the cliff beyond her house. I can make out a few other people. They’re looking at pinpricks of light, tiny jewels in a miles-long necklace, twisting across the Golan Heights toward us. Tanks. Someone in the blackness asks, “Theirs or ours?”

“I don’t know,” comes the reply. “But we’d better go to the bomb shelters.”

Lying on my back on a wooden bunk in a shelter deep underground, I watch the sleeve on my shirt fluttering, as if in a strong wind, from the concussion of the artillery above. The little kids in the shelter are crying. I’m up for hours, unable to sleep for the noise and fear and excitement—and because I’m looking out for spiders or other insects that may have taken up residence in my bunk since the last war. That’s the adolescent mind for you: worrying about creepy-crawlers in the face of death and destruction.

Nights we hunker outside the shelters until it’s time to sleep, listening to the static-swooshed reports of the BBC from London. The kibbutz is spotlit by a glaring harvest moon that makes a mockery of the blackout. A radio announcer informs us that Jordan might send troops to fight alongside its Arab brethren. Those guys are just down the road from us, I think, with a little thrill-seeking shiver. I sit spellbound, listening to the kibbutz members who are assigned to babysit us—veterans all of Israel’s wars—as they debate the ramifications long into the shimmery night.

I go to bed dreaming of Henry Kissinger.

Daytime we pop up above ground for air—prairie dogs from our burrows—during lulls in the fighting. Pairs of Israeli Mirage jets shriek low over the Galilee and into the Golan, so low they make you want to hit the ground for cover. We learn to brace as they drop their load of bombs, then count the seconds until they screech back overhead to base. Several days into the war, when we’re finally allowed back to our rooms to shower, we find a bunch of long-snouted howitzers have taken up residence on the football pitch below. Just as I’m sneaking down to get a peek at them, the commanding officer suddenly shouts, “Aish!” (Fire!) — and I’m nearly thrown to the ground from the explosions. Someone yells at me to get my sorry ass back to the bunker; the Syrians are going to answer the guns any minute now. I gallop to the shelter, sweating and dizzy with fear but thrilled, in a voyeuristic way, to be at the center of world events.

The thing about war—as long as you’re not dying—is that it’s oddly exhilarating. One minute you’re an angst-ridden adolescent moping about your parents, your place in the world, the latest outcropping of pustules on your chin. The next thing you know, you’re sucked into the vortex of geopolitics and a three-week-long conflict, listening with puffed-up importance to worldwide news on the radio about your own situation and spouting off about balance of forces. What could be better? Perhaps if I could foresee that this was a portent of my adult life to come, that war would dominate my existence both as a reporter and as a wife, I wouldn’t be quite so enthusiastic.

But all that is in the future. For now, I’m convinced—with the certitude of any self-absorbed, seemingly immortal teenager—that this is what I’ve been seeking.

This excerpt from Dirty Wars and Polished Silver is published here courtesy of the author. It should not be reprinted without permission.