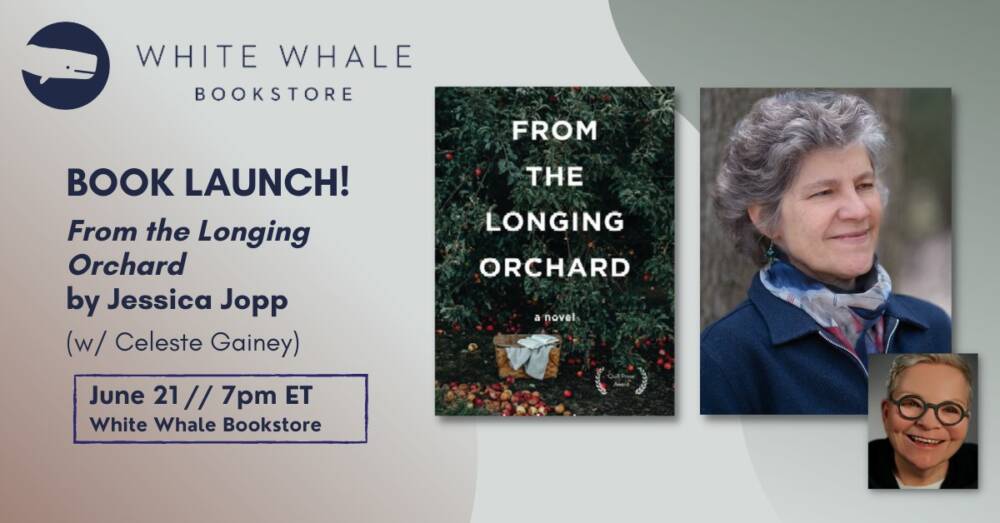

From the Publisher: “Eighteen-year-old Sonya Hudson has been gripped by phobia since she was thirteen. What would make navigating the world so difficult for this budding visual artist? When the story opens, she lives with her mother and her sister in a suburb in New York in the late 1970s. The narrative carries us back through her childhood, where she struggles with the family’s frequent moving and with her parents’ increasingly fraught marriage. Lingering at the periphery of her consciousness is the shadow of a damaged boy she knew when she was very young. Reverence for the natural world provides comfort, as does her fierce attachment to her sister and her parents’ poignant guidance. But it is the intimacy with another young woman that ultimately offers a path to healing. In language soaring with poetic incantation, From the Longing Orchard shows us the ways in which a young woman and those she loves all must contend with a longing of some kind and how they seek from each other, and sometimes find, the needed balm…”

More info About the Author: Jessica Jopp grew up in New York State. She holds an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. From the Longing Orchard is her first novel. Also an award-winning poet, Jopp has published her work in numerous journals, among them POETRY, The Texas Observer, Seneca Review, and Denver Quarterly. Her poetry collection The History of a Voice was awarded the Baxter Hathaway Prize in Poetry from Epoch, and it was published in January 2021 by Headmistress Press. Jopp teaches in the English Department at Slippery Rock University. She lives in Indiana, Pennsylvania, where she is on the board of a non-profit working to protect a community woodland.

Don’t miss out: Jopp will be launching her new novel (with Celeste Gainey) on June 21st!

More info “Jessica Jopp’s From The Longing Orchard is a moving and lyrical coming-of-age story exploring the mysteries of identity, the ways that pain is passed from generation to generation, and the difficulties of overcoming a phobia. Filled with beautiful descriptions of nature and told through the sensibility of a deeply sensitive and observant young girl growing into adulthood and her own queer sexuality, this novel has a quiet but powerful impact that will live on in the reader’s memory.” —Tony Eprile, author of The Persistence of Memory (winner of the Koret Jewish Book Award and a New York Times Notable Book of the Year) and Temporary Sojourner and Other South African Stories, also a New York Times Notable Book of the Year

“Reading From the Longing Orchard is like sifting through layers of fallen leaves and humus on the forest floor, then hopping on a raft to drift along a meandering river to gaze at the clouds. This is a nuanced story of disintegration and renewal, like the seasons; it is a coming-of-age story, a textured love story in which all one’s senses are awakened. I first read Jessica Jopp well over 20 years ago. I loved her writing then, and after all these years, it still resonates.” —Jacqueline Dumas, author of The Heart Begins Here, The Last Sigh, Madeleine & the Angel, and winner of the Georges Bugnet Award for Fiction

“In this novel, words take on the weight of objects, shimmer in images that linger long after the pages are turned. Jopp, a gifted poet, is also a natural storyteller, and she has created a world I want to return to again and again. Breathtaking at the level of language with characters both complicated and alive on the page, From the Longing Orchard will enchant you while it breaks your heart—a perfect reading experience if you ask me. I loved it.” —Anne Dyer Stuart, author of What Girls Learn and winner of the Henfield/Transatlantic Prize for Fiction

1.

Where Was Field?

Then, they lived in a third-floor walkup in Putnamton, on the south side of the city. When her mother held her in the chair on the side porch, gray paint chipping off the floor, the wood soft and slightly tilted, she smelled her mother’s skin. Her father glued shims under the front legs of the chair, so when Sonya Hudson sat with her mother in the sun the world did not feel slanted.

Then there were shadows of the oak beyond her bedroom window and, along with the earlier smell of her mother’s skin, there were scents to be absorbed by daylight and by darkness, textures to be noticed. Then, there was sunlight on her arm or on a chair, before it was sunlight. There were voices in her ear, singing whatever they were saying, one of the many mysteries. Even after language came, it wasn’t this way; there was the summer porch just at dusk, and she knew as red the weighted globes of the cherry tree, draping themselves over the edge of the roof. And beyond that with the orange-pink sky of sunset, she knew the word wide. There were the warm fields she walked with her father, and the sidewalks in town, huge trees lining them, dusting down their shadows in the summer. She knew field and tree. Veined leaf and bumpy pinecone texture, frog-skin texture, night-bug sounds beyond the screen. She knew water her parents took her to, and, while her mother held her hand, both of them leaned into its blue well of scent. The faint green speckled rounds of stone worn smooth, damp in her hands. Each new word, lake, stone, came lifted, dripping, shimmering. With each new word, mysteries deepening.

But here she was at eighteen unable to live for those scents and textures or to leave her house, surrounded in her room by half-sketches, a pile of pen- cils chipped and broken behind her on the floor amid dirty clothes, plates of old food. There were sketches tacked to the wall above her desk, and notes written on the wall, marked in detail with the underlined heading Don’t Forget; so that she wouldn’t forget what to do next, she told herself.

The range of things she could do included starting a new sketch, work- ing on one begun, finishing another. Or lying on the floor, looking up, and thinking about circular images—a constancy in her drawings that Elinor had pointed out—or opening the door to let Lois or her mother in, or walking downstairs to briefly join them for a meal. It did not include driving into town with them or going for a walk with Elinor or riding her bike out the path away from the suburbs and past the shoots of summer green pasture, this summer, the summer of her eighteenth year. It did not even include pulling back the curtains and unlocking and opening the windows, both of them, or, especially, leaving them unlocked at night, or looking at stars netted in them, or sleeping out in the yard as she and Lois did as kids sometimes, or thinking about next year or about any others after this one. Her list of things to do, so that she wouldn’t forget, did not include putting her pillow and sheet on the floor by the open window on a clear night and sleeping in the spill of moonlight coming in her room. She lived in a room in a house with her mother and her sister and beyond them others ordered the world of Harpur Springs, kept the buses running on time, the newspapers delivered. The world was filled with people like Norma Rae who worked hard, spoke up for others, who could stand on a table, hold up a sign, and make life better. When she and Elinor saw the film at the mall that spring, they had been moved to tears by it. Sonya found comfort now, in her room, in recalling such people. All she could do was get up in the morning, sit at her desk, and live in that one moment. The small rolltop had cubbyholes, supplies had their designated place. So that she would not forget which charcoal or sharpened colored pencil to pick up next.

Her mother came in, as she often did lately, and sat down in the rocking chair. “You haven’t been out of this house, this room actually, in weeks and weeks. And I can no longer—I just hate to think of your nightmares about them.” When Sonya was still venturing outside, going about a day, Marie had said she couldn’t bear to see Sonya avoid the animals outside. And then her daughter had said, “I’m fine, Mom, really. I can handle that.” Staying in, she could reduce the risk further, and not even have to avoid one.

Now the direct mention of her nightmares made Sonya cast her eyes away from her mother, down to the bits of scrap paper on her cluttered desk. She felt sweat forming on the back of her neck. Just last night they had been in the trees, hanging above her as she walked the path. She lifted her head briefly and saw their arms and tails loping down, their eyes cast down, watching her. There might have been fifty of them, and they took naturally to the trees. They leapt from one to the next as she walked. They were traveling her way, keeping an eye on her, above her and behind her, and they seemed at any instant about to slip from the mossy gray branches and drape themselves over her. If she were to look at them close-up, as she was sometimes forced to do in her waking life—chancing across one in the neighborhood—they would have yet another chance to threaten with their eyes, taunt with the shredded flesh wedged between their teeth. She had to hurry. When she began to run, the animals moved faster through the trees, and the end of the path, the clearing, moved further from her reach. It was the sweat of running that she had felt on her neck when she woke. But she did not tell her mother any of this. She shrugged.

Instead of saying again that she was fine, she said, “I’m used to them.” It had been five years since her fear began, five going on six, five, with each day infused with it, each day holding its minutes stretched out almost to snapping by the blinding white of fear.

Across the room her mother sighed as she took off her straw garden cap, leaned forward with her elbows on her legs, and covered her face with her hands.

In the very beginning, when Sonya’s parents lived in their first apartment in Putnamton, Connecticut, which they rented for fifty-five dollars a month, a special evening for them was a twenty-nine-cent quart of beer and the cheapest piece of meat her father could get at the Thirty-Fourth Street grocery store on his walk home from work. Her mother fried onions, peppers, and the pieces of liver, and they ate this over spaghetti with a loaf of bread. She had quit her job in the fabric store when her pregnancy started to show.

Born from the old sadness of each, and into their joined promise, was first Sonya and then, eighteen months later, Lois. Since they could not afford to go to the movies or to get a babysitter, Mitchell and Marie Hudson spent every evening with the girls, reading stories or, when their daughters were a little older, drawing with crayons on large sheets of rough scrap paper Mitchell brought home from his job at the paper mill. Sometimes the girls spread the paper out on the black and white checked linoleum floor of the kitchen, and sometimes their mother taped sheets of it to the refrigerator, and they stood up and drew, as if at an easel. They made houses, animals, and cities peopled with specks, the kitchen always wiped clean by supper- time and drawn on fire with color by the next afternoon.

When they moved out of the city, they pulled all their belongings in a U-Haul trailer behind the station wagon with fake wood strips along the sides. Sonya’s parents had bought the car for the move for fifty dollars. Her father had also given the owner as part of the deal two clay birds he had made, finely detailed and carried in one hand. By the time they reached the central farmland of New York State, night had fallen. When her father got out to see why the trailer had slid off the road into a ditch, Sonya was awak- ened by the inside car light. Her sister was still asleep beside her. She heard her father urinate against a hubcap, then pace back and forth on the dark road cursing. The headlights cast their wobbly beam down the county road. Summer, and night bugs scritched in the cornfields on either side of them. Her mother reached her hand back, touched her knee and said, “We’ll be there soon, Honey.” Sonya slept while her father, with the generous help of a passerby, maneuvered the trailer back onto the road. And, though exhausted, he stayed alert the rest of the trip.

Their arrival in the town of Laconius, where Mitchell had gotten a job as a shop teacher, raised the population to three hundred fifty-six. A town this size had but a couple of stone churches, a corner grocery store, post office, and a filling station. Of special notice for those passing through were the handful of Greek Revival houses, here and there, set back from the road, among the mostly typical two-story wood frame houses, the farmhouses on the outskirts of town. Otherwise, fields all around the town stretching for miles, dairy farms plotted among them.

For a month they lived at The Bluebell, a motel a few miles out of town, at the intersection of a town road and a county highway that led to the inter- state. The town’s remoteness was somewhat compensated for by a party phone line, an intimate mode of communication that made possible the occasional inadvertent sharing of private information, and thus occasionally the subsequent intentional disseminating of it. In fact, this is how one party discovered that the Hudsons needed an apartment, and how, eventually, they found one available at the other end of Main Street.

There was not so much fear as wonder then, in the new place they rented when they moved out of the city. The upstairs floor of a house was theirs. Sonya and Lois watched, over the windowsill in the sun porch, as a strange machine carved neat rows in the field beside the house. When their mother taught them the word combine, for days it lay on their tongues like a piece of translucent yellow candy. In this kitchen too, the girls used the refrigerator like an easel.

Now she lived in her imagination, but didn’t everyone, she might have asked herself. She told her mother she was fine. And she was; everyone lived that way. There were colors, textures, and sounds right in her room, and it was all familiar. Sonya didn’t really need to leave her room for anything; after all, there wasn’t anything else she needed. She could wear her clothes the right way, then inside-out awhile, then right-side out again. Food was not far away—downstairs in the kitchen. Her pencils and paper would last, and she had so much work to do that there just wasn’t time to spend with Elinor or Lois anyway. They could come to talk with her, which they did. Her mother, too. But usually that was brief, her mother looking worried or trying to talk with her about getting out to check the garbage can lids or to carry a planter outside for her. Sometimes Sonya could manage these things.

Or her mother appeared otherwise pained, though tall, assured, asking her daughter to venture into the world with her, to the store or to an event of some kind, as if she could merely step beyond the threshold and carry herself among all those details, all those people going about their days. All that movement to absorb, sound to hear and make note of. When she declined the offers, she saw the gray of Marie’s eyes turn inward, retreat a shade to that reserve of strength in times of disappointment. Even so, Sonya couldn’t help but decline; far better to stay inside where she could take care of things herself, keep track of the path of light across her room during the day, the sounds of the neighborhood heard faintly through the closed windows, recall the efficiency of others beyond her street and let them keep that up, keep everything running smoothly. She had artwork to do and did not want to forget what to do next.

Or her mother was quiet, sitting in the chair in Sonya’s room, turning the silver ring on her finger while looking down at it, and hesitating. The quiet accentuated her musk oil perfume. In that pause Sonya could go elsewhere, the weight of the present too much to take in; with no deliberate figuring on her part, she was back in the summer kitchen, the checked linoleum cool to her feet, her mother braiding Lois’s hair, when her father came up the back steps, face contorted in worry, reddish-brown eyebrows knitted nearly into one. His thick red-brown hair, though short, a little wild, from his hands running through it in distress.

“It’s Lloyd Duncan’s son,” he had said to Sonya’s mother, referring to the fifteen-year-old who lived in the house on the other side of the field. “He and the Mancini boy were making an explosive of some kind, and it blew up in his face. He ran from their barn to the house. Collapsed on the kitchen floor, he lost so much blood. Blew off half his face. Stupid kid. He could have died.”

Sonya’s mother had put her hand over her mouth and closed her eyes, then opened them with the same look of concern that was evident now. “My God,” she had said.

The word collapse had been new to Sonya and so full of significance she could hardly absorb the information. She imagined Andy Duncan, a teen- ager and thin, collapsing onto their kitchen floor. Blood would fill the tiny cracks and blur the squares. Her mother, father, sister, and she herself, would lean over him. They would fall into him, into the gape in his face, become part of his pain. Collapse must mean the rest of the world falls too, falls into the wounded person.

It had been just a few days earlier that she and Lois were sitting on the back steps in the sun sorting chalk for the sidewalk when he walked across the field, hands cupped in front of him. The girls looked up as he approached and asked them if they wanted to see what he and his friends had found that morning on the side of the road.

Sonya noticed his short dark hair combed back, a few freckles on his face matching the ones on his arms. He seemed almost grown up, with his white T-shirt, marked by a sweat patch here and there, hanging over his khaki shorts.

The girls looked at each other. “OK,” they said.

“Here it is, in this box.” With one hand Andy carefully lifted the top of the earring box, the name of a department store, Murphy’s, slanted across it, which was in his other hand. Resting on the square of cotton was a finger, red apparent bloodstain at its base, which seemed to be absorbed by the fibers around it. The finger had dust and dirt embedded in its dried blood.

He saw their horror-stricken look and launched into embellished details. “There it was, lying there in the dirt by itself, not even wriggling anymore, and we stopped to pick it up and it was cold. The tip was almost purple.”

The girls could hardly breathe, struggled to find air to form a word. “But whose is it?”Sonya asked. “Won’t someone be looking for it?”

“Well, finders keepers,” Andy said, putting the lid back in place. “It’s mine now.”

Lois grabbed her sister’s arm. Sonya said, “We have to go in now.”

“Any time you want to see it again, just let me know,” Andy said, smiling as he turned to cross the field and head home.

When they had run in and told Marie about it, she sat them down and explained that it was not possible that he had found a finger.

“But we saw it.”

“It was in the box.”

“But how could a person lose one finger like that?” Marie tried to pacify their stupor. “It doesn’t make any sense, girls. He must have played a trick on you.”

Though they were inclined to believe her, the nauseated feeling they had had at seeing it lingered with them the rest of that day and into the next.

Now came the news of his accident. Thinking about his freckled cheek, Sonya tried to imagine his face blown apart but could not. “Will he be able to talk?” she asked her mother.

“Probably when his mouth heals, yes,” she said. “Finish your peach.” Sonya imagined his mouth healed, back in place.

She picked up the half-eaten peach she had set aside to better hear her parents’ conversation. Her father went back outside. Eating the peach slowly, thinking about her teeth and about the fuzzy skin and sweet juice, she watched her mother braid her sister’s reddish-brown hair. She couldn’t imagine not being able to open and close her mouth around a peach. The phrase could have died hung in the air like a bat.

“What is heaven?” The linoleum floor was cool to her bare feet. Her mother’s hands paused in her sister’s hair as she looked at Sonya, the gray of her eyes, as usual, earnest, intent on her daughter’s question.

“Some people believe it is the place a soul goes after a person dies.”

Sonya held her peach in her left hand, wiped the juice from her right hand onto the front of her blue flowered cotton sundress, took the peach again in her right hand, and asked, “If Andy Duncan died, would his soul go to heaven?”

“Yes, I think it would,” said her mother, braiding Lois’s hair again.

“Could he feel pain in heaven?”

“No, he would feel peace there, Sonya.”

“Would his mouth be healed so he could eat?”

“People don’t eat in heaven.”

“Can they smell anything?”

“No.”

“Can they hear?”

“No.”

“Can they see?”

“Sonya.” She watched her mother wrap a rubber band around Lois’s braid and brush the end, careful not to pull it. The girls were beginning to experiment with her hair, too. Hers was short though, so with limited styling options this meant that they stood on a chair on either side of her and combed her dark hair sometimes all forward, then all back, sometimes from one side to the other. Barrettes and other accessories were likely to come soon. Occasionally she let them help her tease it up.

“They don’t play no games?” Lois asked, a puzzled look on her face, its usual hint of round wonder, openness about it, subdued.

“They don’t play any games,” her mother corrected.

“They don’t play any games?” There was a note of alarm in Lois’s voice.

“What can they do?” Sonya asked.

“They are souls. They don’t exist in the world as we know it, but in a different world.”

Sonya sucked on the peach pit to get the last hairy strands of fruit.

“Please don’t suck on the pit, Honey.” She spit it out on a plate.

“Souls understand more than we can ever imagine. They don’t need our senses. They have their own, more precise and better than ours. They are happy. It isn’t something you girls should be worrying about.”

Sonya did not know what precise meant, but she knew happy. She was five.

Later that afternoon when the girls spread huge sheets of paper out on the floor of the sun porch, Sonya drew Andy Duncan fallen on the floor. She gave him pots and cups and peaches around his body. She took a magic marker, double red, and drew all of his blood streaming back into his body through a sprawling gap where his mouth should have been. Then she asked her mother to write out the title, Andy Duncan Collapsed in the Kitchen, at the top in purple crayon.

That night Sonya dreamed that she hovered in the air with a winged woman dressed in white. Far below them in the black landscape someone sat holding his face together. The woman said to Sonya, “He almost died.”

Every night for the next few weeks she listened in bed to Lois breathe and watched shadows the streetlights made. The rest of the house was quiet. A stately oak tree in the front yard stood between the house and a streetlight, and animals took shape on the walls. Their mouths seemed to move as if speaking, but she could not make out what they were saying. Sometimes a car drove down Main Street and cast its headlight beam through the room like a flashlight. Their room was sunk in ghostly shadowed light that was familiar to Sonya, and sometimes she felt as though she was on a ship that had sunk years ago. Perhaps the other world her mother spoke of was like this. She and Lois were not in air or water exactly. They might never again be up walking around in the clear light of the yard or of the kitchen. When she had to use the bathroom, she woke Lois to walk down the long hallway with her. The porcelain toothbrush holder with a neat red, blue, and two smaller pink brushes in it jutting out from the wall told her that the world was safe and that morning would come.

On the way to Andy Duncan’s house with her mother and Lois, two weeks later, when he was out of the hospital, Sonya thought more about the word collapse. Walking across the warm summer field she wondered, was he still collapsed, was he going to look collapsed, or was it something a person did once and then was finished doing?

“Is he still collapsed?”

“No, that was just at first. He is recovering now.”

“Can he talk yet?”

“I’m not sure. We’ll see, girls. And if he seems very tired we won’t stay more than a few minutes. He probably needs a lot of rest as his face heals.” They reached the gravel driveway and crossed to the back screen door of the two-story wood frame house. As Marie was about to knock, Lloyd Duncan approached from the kitchen and opened the door.

“Hello, Marie, girls.” He nodded toward them. He was stockier than their father, thick was the word that came to Sonya from close-up, his shoulders broad, face almost square, his dark hair short and brushed flat on top like the hair of most of the men in town.

“The girls thought it would be nice to see how Andy is doing.”

“Come on in. He’s in the living room now on the couch. Not good for much help with the summer work, but what are you going to do?” He directed the question toward Marie, though it didn’t need an answer. “If my wife was here, she’d get you a glass of water or make you some iced tea, but she’s run off to the store.”

“That’s all right,” Marie said. “We’re fine.”

As he led the way from the kitchen, Sonya noticed that the bare metal table had its matching chairs all pushed in. From the next room came a sound the girls recognized but hadn’t heard too often, the midday game show chatter. They followed Mr. Duncan into the living room, where he walked over to the large wood-grain box with the doily and the plastic plant on top of it and snapped it off, the picture fading from the edges and disappearing through a spot of silver light in the center, until the screen was completely black.

Then they all turned toward the couch, where Andy reclined on his side facing the TV, wearing shorts and a T-shirt. The bandage wrapped around his head seemed to nearly swallow him, a small space for his eyes and an opening for his mouth, his hair matted and stuck to him in sweat. As he lifted an arm and gestured hello, Sonya noticed a glass of water on a table beside him with a straw in it.

“Hi, Andy,” Marie said. “The girls wanted to come over and see how you are doing.” Sonya and Lois said hi, and he looked at them and nodded.

“Well, there he is,” his father said. “You are welcome to sit and have a chat.”

Marie and the girls sat down in armchairs, all covered with thick plastic.

His father remained standing. “There is Mr. Explosive of 1966. Good thing you didn’t come over to see what he is doing, because all he is doing is lounging there like a beauty queen. That’s it, you see it! Probably couldn’t even mow the lawn.”

The girls, wearing shorts, shifted in their seats, peeling their legs from the hot plastic.

“Christ, when I was his age I had half the county lit up from explosives I’d made with my buddies out in some field. That’s what we knew how to do—hunt, fish, torch crap up. You girls wouldn’t know about that. I figured he’d like trying it too, but this one couldn’t make a goddamn—excuse me— firecracker without nearly doing himself in! Isn’t that right?” He glanced down at his son. “That army better hope to hell it don’t draft you down the line. You might blow up your own unit before you get halfway over there to Vietnam.”

Andy looked up at him and nodded.

“Good for I don’t know what. Hey, he’s all yours, girls. I’ve got work to do if you’ll excuse me.”

“Sure, Lloyd,” Marie said. “We’ll see ourselves out. Thanks.” He walked back through the kitchen and out the door.

The brunt of what he had said, the weight of it, bore down on them in the hot living room.

Then Marie turned to Andy. “Will the bandage be on much longer?”

He nodded that it would be.

“Does it hurt to talk?” Sonya thought that it might but wondered if he could.

He nodded, then slowly sat up and reached toward the table to pick up a pad and pencil beside the water glass. He jotted for a minute or two and handed the note to Marie.

She read it out loud. “The doctor said it will take longer to heal if I try to talk now. It could be another couple weeks before I can open it more so it will be easy to talk and eat. But now I can eat soft food.”

“It’s good you can eat,” Sonya said. Andy nodded that it was.

He picked the pencil up again and wrote a bit more, handing the page to Marie, who again read.

“There is a hole in the bottom of the box. We didn’t really find the finger, it was one of my fingers. It was a trick my friend got from a book. I’m sorry if I scared you.”

The girls watched him closely as he held up his hands and motioned the way his middle finger slipped through the hole so that it nestled on the cotton in the box.

Then Sonya asked, “It was really just a trick?”

When he nodded, each of them let out a breath of relief.

Marie smiled at him. “I’m taking the girls to the Five-and-Dime later. Can we get you anything?” He shook his head.

“Girls, Andy probably needs to get some rest now. We should go.”

They stood up, legs peeling off the plastic, and stepped toward the couch.

“I hope your mouth gets better,” Sonya said, as Lois leaned toward him and more closely inspected the bandage.

Andy looked up and whispered, “Thanks for coming,” his mouth barely moving.

Marie rested her hand briefly on his shoulder and smiled at him again.

Then they walked into the kitchen. Sonya peeked over her shoulder into the living room and saw Andy still sitting up, glancing through the doorway at them. When she caught his eye, he eased himself down, reclining, and gazed toward the blank television. They let themselves out the screen door and headed back across the field toward their apartment.

“Why is his father mean?” Sonya asked.

“It might be because he is upset that Andy has been hurt.”

She thought about her mother’s explanation. Maybe that was it. Yet there was something strange about his father.

When they reached their own back steps, Marie paused before leading the girls up the stairway to the second floor. She bent down and hugged each of them.

“I love you two.”

They slipped their arms around her neck and held onto the scent of her summer heat.

And at times during her childhood the earth felt wide and smelled warm to her, and, this day, her father’s hand up above leading her, with Lois on his other side, seemed to say: I am up here among the tall things, closer to the tops of trees, closer to the sky, walking this round earth longer, come this way, I will show you. They walked out across the playing fields, stepped into the lengthening sun of late day, stepping blade over blade over blade through sun, their own shadows stretching down to the warm grass. They stooped now and then to pluck a white puff whose name she learned that day and drop it in a brown grocery bag, treasure left behind, the field scattered with such finds that her father exclaimed with great joy, “Look, here’s another one! Today must be our lucky day!” at each earth-smelling round. After the length of the field, they walked back home, in his hand a bag of the round discovered things that no one else had found and called his own. The luck of another day in which she and Lois learned a word. When they got home and he poured them out on the kitchen table, his wife hugged him and said, “They look delicious, Mitchell.” That evening she rinsed them in the sink, took out a frying pan, and soon their kitchen was filled with the earthy smell of the cooking slices.

But where was mushroom now? That place of damp wonder had had rain in it, the cool exhilarating kind someone could linger in. Or a deserted county road perhaps, that she had seen from the car window, the fields in rain, the day in mushroom. Now, at eighteen, if she thought about it, the word would remind her of her no-wandering. In a word like mushroom was a hint of what was lost. She had not fallen, though, to the summer floor in pain, her body damaged by recklessness, the place where a mouth had been now floating in spilled blood, its absence unimaginable to the psyche that was likewise diminished. Who was that boy from her early childhood? Had he recovered? If she tried to, she could not recall. Hers was not a physical scar; no shredded flesh dangled, unhealed. She can talk, she can, she does. She’ll show her mother that she can.

“I’m fine, Mom,” Sonya tried again. She spoke loudly in her dreams; she screamed in them sometimes. “Please don’t worry.” Where was field? She’ll feel the damp joy of mushroom again, the wonder of starlight caught in a night window, melted to waves in the glass, the abandon of a summer storm moving across the reservoir.

Glenda had gotten out of it. Surely she could. But her grandmother was still confined by depression to some degree; she herself wouldn’t be. There was nothing that wrong; recovery wouldn’t be very dramatic. She would simply get up and go about her day. One day she would do that, and she would sleep through a night. One day soon, but for now she needed to focus on the notations in pencil above her desk with the heading Don’t Forget; so that she wouldn’t forget what to do next, she told herself.

She started to say “Don’t worry” again, but when she looked away from the wall above her desk and back to where her mother had been sitting, Sonya realized that she had already left the room. When had she left? Had she walked over and rested her hand on her daughter’s shoulder? Had she walked over and kissed the top of her head? Sonya did not know how long she had been sitting there, contemplating the notes above her desk.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.