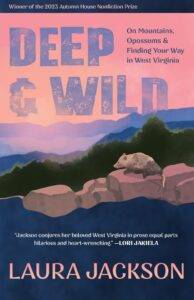

Tom McMillan — Bellevue, Pennsylvania native and Point Park University alumnus — is the author of Flight 93: The Story, The Aftermath and The Legacy of American Courage on 9/11 and Gettysburg Rebels: Five Native Sons Who Came Home To Fight As Confederate Soldiers. He serves on the board of trustees of Pittsburgh’s Heinz History Center, the board of directors of the Friends of Flight 93, the marketing committee of the Gettysburg Foundation and as a tour guide at the Civil War room at Carnegie Library in Carnegie, PA. He’s spent a lifetime in communications as a newspaper sports writer for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, among others, as a radio talk show host, and, for the past 21 years as VP of Communications for the Pittsburgh Penguins!

From the Publisher: “Gettysburg Rebels is the gripping true story of five young men who grew up in Gettysburg, moved south to Virginia in the 1850s, joined the Confederate army – and returned ‘home’ as foreign invaders for the great battle in July 1863. Drawing on rarely-seen documents and family histories, as well as military service records and contemporary accounts, Tom McMillan delves into the backgrounds of Wesley Culp, Henry Wentz and the three Hoffman brothers in a riveting tale of Civil War drama and intrigue…”

Author’s Note

I was different from other Gettysburg battlefield trampers. I was often drawn to obscurity.

I would whisk past Devil’s Den and Little Round Top and the field of Pickett’s Charge to find myself at an often-ignored corner of the Emmitsburg and Wheatfield Roads, where a plain iron tablet next to an old stone foundation reads simply, “Wentz House.” How poetic.

It was here that an elderly Adams County resident, John Wentz, crouched in his cellar during the battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, unaware, at least at first, that his son, Henry, who had grown up in that house, was posted six hundred yards away as an artillery sergeant in the Confederate army.

Henry Wentz’s homecoming as an enemy soldier has intrigued me since the day I first read about it in Harry Pfanz’s Gettysburg: The Second Day. I wanted to learn more about him—to read and study more, to advance the story in my own mind—but, alas, very little was available in books. Like many other soldiers in the Civil War, Henry did not write about his experiences, or if he did, nothing has survived. No one has seen his photo or any of his possessions. He was, and is, a mystery—and perhaps he preferred it that way.

But I decided to explore. I came up with an idea to write a book about two young men from Gettysburg who had fought as Confederates in the battle of Gettysburg—Henry Wentz and Wesley Culp, whose name is better known because of his family’s hometown roots. In the process, however, I learned that three brothers named Hoffman had also grown up in Gettysburg and become Rebel soldiers, and that all three had direct connections to Culp.

Thus, Gettysburg Rebels was born.

The research was a challenge because Culp was killed in the battle, and none of the others wrote about his actions during this cataclysmic period in the nation’s history. Aside from Culp’s, no portraits of the men exist (though perhaps an unknowing descendant will dig into a box and come forward with one after this is published). But I decided that a lack of such traditional evidence should not deter me. These men’s stories still deserved to be told.

Uncovering those stories took me on an amazing journey to places I’d never been (Shepherdstown and Martinsburg) and some I’d never heard of (Linden and Warrenton), in addition to Harpers Ferry and Gettysburg. I scanned countless pages of oversized county deed books that probably had not been opened for a hundred years and sifted through wills, tax records, church records, newspaper advertisements, family files, obituaries—and, of course, military service records and pension applications at the National Archives. I met and was helped by many wonderful people along the way.

The story in these pages is certainly not the complete account of Henry Wentz, Wesley Culp, and the three Hoffman brothers, but I’m convinced it is the closest anyone has come. Perhaps it will spark more dogged research and the uncovering of more clues (maybe even a photo).

In the meantime, I hope that you enjoy the narrative presented here—the story of five young men who grew up in the North, fought for the South, and marched on their old hometown with an invading army in July 1863.

However you judge them, they will no longer be obscure.

Tom McMillan

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

December 2016

Introduction

Fifty miles from the Gettysburg battlefield, on a gently sloping hill behind the Green Hill Cemetery mausoleum in Martinsburg, West Virginia, a weather-beaten and barely legible tombstone marks the final resting place of one of the fascinating figures of the American Civil War.

Henry Wentz

Died December 10, 1875

Aged 48 Years

The stark memorial offers no tribute to his four years of artillery service for the Confederate States of America, makes no mention of his deeds on fields of honor at Manassas, Sharpsburg, Mechanicsville—or, hauntingly, Gettysburg. It is as though the friends and family of Henry Wentz did not comprehend the extraordinary role in America’s great cataclysm of a man who invaded his old hometown with a foreign army and fired on the house where he grew up.

Born in nearby York County, Pennsylvania, in 1827, Wentz was just turning nine years old when his family moved to the Gettysburg area.2 His father, John, bought a one-and-a-half-story log and weatherboard house along the Emmitsburg Road in Cumberland Township, barely a mile from the Gettysburg town line and adjacent to a peach orchard that would one day merit its own place in American history. Henry spent his formative years there, maturing into adulthood and becoming a local land owner himself before moving to northwestern Virginia in 1852. He settled in Martinsburg (in what became West Virginia), found work as a plasterer, joined a local militia unit called the Martinsburg Blues, and enlisted in the Confederate army when war broke out in 1861.

If Orderly Sergeant Wentz felt a strange queasiness two years later as the Army of Northern Virginia thundered into south-central Pennsylvania, he would not have been alone. Four other men in Robert E. Lee’s invading force had grown up in Gettysburg. John Wesley Culp, from one of the borough’s most prominent families and a private in Company B of the Second Virginia Infantry, was immortalized when he fell in battle near his cousin’s farm. The three remaining Gettysburg Rebels, however, were unknown even to Civil War historians for well over 130 years.

These were the Hoffman brothers—Robert, Frank, and Wesley. Their father, C. W. Hoffman, had been one of Gettysburg’s leading citizens, but in 1856 he suddenly, and somewhat mysteriously, pulled up stakes and moved to northwestern Virginia, with profound consequences for the lives of four future Civil War soldiers. Wesley Culp, a sixteen-year-old apprentice in Hoffman’s Gettysburg carriage making business, went with his boss, helping him open a new shop in Shepherdstown, in what became West Virginia. Culp joined the local militia known as the Hamtramck Guards and eventually entered the Confederate service when the unit became Company B of the Second Virginia Infantry in 1861. And yet most historians have overlooked the story of Hoffman’s own sons, who also moved south with their father.

Robert Newton Hoffman, the eldest of C. W. Hoffman’s surviving sons, worked alongside Wes Culp at his father’s carriage shop in Gettysburg. Like Culp, Robert joined the Hamtramck Guards after arriving in Shepherdstown and enlisted in Company B of the Second Virginia when their adopted state seceded in April 1861. He was with Culp at the battle of First Manassas and other major engagements with the famous Stonewall Brigade. Though no longer in a combat role by the time of the Gettysburg campaign, Robert came north with Lee’s army and served throughout the campaign.

Francis William “Frank” Hoffman, the middle brother, enlisted in the Confederate army as an infantryman at the start of the war but soon transferred to artillery service. He served in Company A of the Thirty-Eighth Battalion Virginia Artillery for four years until being wounded at Petersburg, Virginia, in March 1865. Frank’s company arrived on the field at Gettysburg on the morning of July 3 and played a key role in the great cannonade that preceded Pickett’s Charge.

Wesley Atwood Hoffman followed his older brothers into the Confederate service in March 1862, enlisting in Company A of the Seventh Virginia Cavalry, the “Fauquier Mountain Rangers.” Though his Gettysburg service is more difficult to document than his brothers’, there is strong circumstantial evidence that he was with the Seventh Virginia throughout 1863 and during the Gettysburg campaign, when it took part in the battle of Brandy Station in early June, guarded the mountain passes under General William “Grumble” Jones on the move north, and fought in the cavalry action at Fairfield on July 3.

The first mention in print of the Hoffman brothers’ connection to the battle came only in 1995, when the great Gettysburg researcher William Frassanito identified Robert in his book Early Photography at Gettysburg. Frank’s presence as an invading soldier on his native soil was overlooked until 2015, when James A. Hessler and Wayne E. Motts briefly mentioned him and Robert in a sidebar in Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. The third brother, meanwhile, has been a cipher to Civil War historians for more than a century and a half; Wesley Hoffman’s service in the Confederate cavalry is detailed here for the first time.

I have scoured the military, legal, and family records to reconstruct the stories of all five Confederate soldiers who returned to Pennsylvania as invaders in 1863. Though the names of Wesley Culp and Henry Wentz have been known to serious students of the Gettysburg campaign, the two are barely mentioned in the classic single volume histories of the battle, and their stories are almost never told together. Culp is familiar largely because of his connection to the Gettysburg heroine Jennie Wade and because he fell in battle on “his uncle’s farm,” but I have uncovered convincing evidence that puts the previously accepted date, site, and family relationship in dispute. Wentz merits a mere eight sentences in Harry W. Pfanz’s 438-page epic, Gettysburg: The Second Day, and even Pfanz can only conclude that his role “must remain as one of the tantalizing mysteries of Gettysburg.” My goal has been to conduct a more thorough examination of the Culp and Wentz stories and to place them in context with the heretofore anonymous Hoffman brothers.

The book will also probe the fascinating and complex background of C. W. Hoffman, whose prominence as a Gettysburg business owner and civic leader is understated by historians who identify him only as a “carriage-maker.” Hoffman had direct connections to four of the soldiers—his three sons and Wes Culp—exerting a strong influence over the Gettysburg Rebels. It is also possible that he knew Henry Wentz, for modern-day Hoffman descendants say C. W.’s sister lived as a tenant on the Wentz property in the late 1840s (when Henry was still at home). Gettysburg in the mid-nineteenth century was a very small town.

Beyond those personal details, Gettysburg Rebels will highlight the astoundingly inefficient communication within the Confederate army during the campaign, a weakness that prevented Lee and his senior staff from realizing they had five men from Gettysburg in their ranks. Brigadier General James Walker of the Stonewall Brigade was aware that Wes Culp had Gettysburg ties, allowing him to visit his sisters in town on the night of July 1, but there is no evidence that Walker conveyed this important information to his division commander, Edward Johnson, or to his corps commander, Richard Ewell. None of the other colonels or generals overseeing Culp, Wentz, or the Hoffmans made any mention of the hometown connections in their battle reports or postwar memoirs. We are left to conclude that no one in authority other than Walker was aware of the potentially rich sources of local intelligence among the Confederates’ own ranks.

By contrast, some of the foot soldiers in Company B of the Second Virginia were well aware that both Culp and Robert Hoffman were from Gettysburg—Private Benjamin S. Pendleton requested that pass from General Walker for his friend Culp on July 1—and one member of Henry Wentz’s artillery battalion knew that a fellow soldier had family living on the Gettysburg battlefield. But apart from Pendleton’s request for Culp’s pass, it appears that none of these men in the ranks thought to pass the information up the chain of command.

Thus was Robert E. Lee deprived of rare intelligence assets that could have provided crucial information during his bold and historic invasion. It was not uncommon for Civil War commanders to identify soldiers in their units with local ties and temporarily assign them as scouts or guides. General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson tapped Private David Kyle of the Ninth Virginia Cavalry for such a role at the battle of Chancellorsville because Kyle had once lived and hunted nearby; Kyle, it was said, knew “every hog-path.” The need for local knowledge was especially acute at Gettysburg because General J. E. B. Stuart’s Confederate cavalry did not reach the field until the afternoon of the second day of the three-day battle. “Lee was entirely in the dark as to the terrain and any features of any likely battlegrounds,” writes Stephen W. Sears in Gettysburg, his history of the campaign. Had Stuart been on hand earlier, as expected, Sears believes, he would have been “in position to reconnoiter most of the ground between the converging armies.” But he was not. Certainly, any of the five Gettysburg rebels could have helped in that regard.

One of the famous missteps in Confederate strategy took place early on the morning of July 2, when Lee sent his topographical engineer, Captain Samuel Johnston, to scout the Union left flank. A Virginian with no previous knowledge of the Adams County landscape, Johnston informed Lee that from the summit of the hill known to history as Little Round Top he saw no enemy troops in the vicinity—a compelling report for the commander of an invading army and one that had a powerful influence on Lee’s battlefield assessment that morning. But as Harry Pfanz writes, “Captain Johnston made an incorrect report to his commanding general.” Historians have concluded that Union troops were indeed present in the area of the Peach Orchard and Little Round Top that morning. Lee’s July 2 battle plan was therefore based on a hopelessly flawed scouting report.

How did Johnston make such a mistake? The eminent Civil War historian Allen C. Guelzo offers one possible explanation: “Federal troop movements made Johnston’s claim to have ridden straight up to the summit of Little Round Top unopposed and with nothing to observe simply incredible—unless, of course, Johnston had not been anywhere near the Round Tops in the first place.” The captain apparently did not have an Adams County map in his possession, and it is possible that he mistook one of the many other hills in the region for Little Round Top. We can never know for sure, but under any circumstances and regardless of where he went or what he saw, he could have used a local man to guide him.

Unfamiliarity with the terrain took another toll later on July 2, when Confederate troops under General James Longstreet were marching into position to attack the flank that Johnston had already misidentified. Hoping to surprise the Federals, Longstreet instructed his division commanders to avoid being spotted by troops from a Union signal corps posted on Little Round Top. The unfortunate Johnston accompanied them to show the way. Alas, when they crossed a bald hill near the Fairfield Road about three miles from their destination, they came within long-range view of the flagwaving signal men. The 14,500 Confederates were compelled to turn around and counter-march several miles to reach the assigned position, costing them valuable time and delaying the start of the fateful attack.

By way of contrast, a rebel artillery battalion of twenty-six guns under Colonel Edward Porter Alexander had faced the same challenge earlier—on the same hill, with the same perspective of Little Round Top—and had made it into position undetected. Turning off the road and cutting across fields, they zig-zagged down the slope into a narrow valley and onto the edge of Warfield Ridge, then waited idly while the counter-marching infantry found its way. Was it mere coincidence that Alexander’s battalion included Captain Osmond B. Taylor’s Virginia Battery, and that the battery’s orderly sergeant was the onetime local Henry Wentz? Neither Alexander nor Taylor mentioned Wentz in his battle report, so perhaps their seamless arrival at the assigned position was simply good luck. We can never know for sure.

But this was Wentz’s back yard. When the rebel gunners crossed the rise beyond the Fairfield Road and began their descent to the valley, the site of his boyhood home was visible in the distance. His parents and youngest sister still lived in the house where he was raised. Colonel Alexander, trained as an engineer, had been assigned by Longstreet earlier that morning to reconnoiter the ground and find an acceptable route for his unit, but it strains credulity to think that Wentz would not have mentioned his intimate knowledge of the landscape to his fellow soldiers if not to any of his commanders. Wouldn’t someone have passed it on?

Sadly, neither Wentz nor any of the Hoffman brothers wrote about their experiences in the Civil War, and Culp was killed in action during the battle, so we are left to speculate about the thoughts, emotions, and actions of these soldiers as they approached their hometown. Few men have found themselves in such remarkable circumstances. Of the 75,000 rebel soldiers who came north with Robert E. Lee that summer, five had spent their childhoods playing in the streets and fields of the town that would become the bloodiest battlefield of North America. The mystery and poignancy of the story of the Gettysburg Rebels make it one of the most intriguing episodes of the Civil War.

This excerpt of Gettysburg Rebels by Tom McMillan is published here courtesy of the author and the publisher, Regnery History. It should not be reprinted without permission.