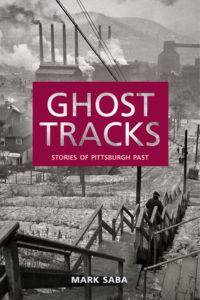

“The stories in Ghost Tracks are indeed haunted, but not by poltergeists or any other supernatural monsters. Instead, these beautifully-rendered works of short fiction are haunted by memory and missed opportunities. Mark Saba excavates a city of Pittsburgh where the factories are still producing steel and the men still have to speak in shards of blunt metallic language, where shades of meaning hover like ghosts between the words.” — Craig Fishbane

About the author: Mark Saba grew up in Pittsburgh and is the author of The Landscapes of Pater and two collections of poetry, Painting a Disappearing Canvas and Calling the Names, as well as several other fiction ebooks available from Smashwords. His fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction have appeared in literary magazines and anthologies around the U.S. and abroad. He’s a graduate of Wesleyan University and Hollins University. Also a visual artist, he’s created oil paintings and poetry videos and is a graphic designer and medical illustrator at Yale University. For more information, visit him at www.marksabawriter.com.

• 1965 •

Asthma

The room was now green, like the little wormy crab apples he and Will picked off the ground at the edge of the woods, bit into once, then threw as far as they could down the hill. He spent a lot of time in that room, his brother and sister at school, mother trudging up and down the stairs with armfuls of laundry, cleaning supplies, and ginger ale for him to drink. She let him stay in bed, but he didn’t much like it, because it reminded him of not sleeping and the dark, and that dry taste in his mouth. Her friend, Frank, had painted his room just before Christmas. It was now apple-green. Before that it had been blue like the Blessed Mother.

The room was now green, like the little wormy crab apples he and Will picked off the ground at the edge of the woods, bit into once, then threw as far as they could down the hill. He spent a lot of time in that room, his brother and sister at school, mother trudging up and down the stairs with armfuls of laundry, cleaning supplies, and ginger ale for him to drink. She let him stay in bed, but he didn’t much like it, because it reminded him of not sleeping and the dark, and that dry taste in his mouth. Her friend, Frank, had painted his room just before Christmas. It was now apple-green. Before that it had been blue like the Blessed Mother.

Frank had a loud voice, or maybe it was the case that all men did, and Luke was not used to hearing a man’s voice in his house. Frank was loud, but didn’t talk much — just smile, especially when talking to his mother.

From the apple-green room Luke went directly to the bathroom for a drink of water, coughing only once along the way. The morning feeling in him was hollow, as if a tornado had blown inside him during the night and left nothing but a bruised windpipe through which he had to breathe. Breathing was painful, something he’d rather not do, but water and ginger ale could take away the burning for a minute or two.

He looked in the mirror and saw sad eyes, though he did not feel sad. They were half-closed eyes, surrounded by gray. His hair was tasseled and his skin looked like pie dough. The only thing that felt good right now was his soft pajamas. On the way back to his room he heard the floor register begin to rattle, and knew he could warm up his feet by standing over it and letting the burnt-smelling furnace air blow through him. While standing there, seeing how long he could take it before the grate burned his feet, he looked through the window and saw a gray sky, and the first few snowflakes of the season blowing back and forth. Today was the day he had to go to the hospital. Maybe they would have chocolate pudding there, as there was rumored to be, and television through all hours of the night.

She didn’t say much during the drive. He watched the clouds billow up from behind the hills until they passed the steel mill, with its own thick, yellow-and-orange cloud maker. Driving along the mill made the car feel a little colder, because it blocked the light, but he liked watching the jets of flame against the uneven black silhouette. It made him feel important, and forget his coughing.

He recognized the hospital, because he had just seen his grandfather there during the summer, waving from one of the windows in his undershirt and back brace. He looked up to that same window now, and found it bare. All of its windows were closed, because winter was already here and all the sick people must be cold.

Come on honey, she said, helping him out of the car like she never did. It was a busy street for a hospital to be on: the City. She carried his bag and held his hand very firmly. Inside, the place was full of nuns. There was an old one sitting at a fancy table when you came in, and she gave him a lollipop. Her teeth were yellow when she smiled.

Dr. Stendhal came around to check on him in his room: it was green around the bottom and white around the top, and there were three beds against each of two opposite walls. Dr. Stendhal still had that scary, clean smell, even outside his office. He listened to Luke’s lungs and told him to breathe and breathe. But there was no coughing now. Next he asked Luke’s mother to step out into the hallway so they could whisper. That’s what people did most often in hospitals: whisper. After the doctor left it was time for his mother to go. She looked away while hugging him, and said she would say a prayer for him before she went to bed.

He smelled dinner before it came, but could not figure out what it was by the way it smelled. A nurse brought it in on a tray, but he still couldn’t tell what it was because it was all covered up with upside-down pie pans. She set it on the little table that was attached to the side of the bed and swung over in front of him, and uncovered the biggest pan. What he saw was a bowl of green vomit.

“What is this?” he gasped.

“Pea soup. It’s good, sweetie. Try some.”

“Could I have some buttered noodles, please?”

“No-no. You’re on a liquid diet.”

“What’s that mean?”

“It means you can only have liquid things — like soups, juices, you know. Liquids.”

For the first time since coming to the hospital now he began to cough, a long uncontrollable cough that reminded him of the burning in his throat. He went for the Jello.

“Nu (cough) — Nu (cough) — Nurse?”

“Yes, sweetheart?”

“I guess I could have a milk shake then? (cough)”

“What a smart kid you are! I’ll see what I can do about that for tomorrow. Just try the soup for now, though. It’s real good. I’m not a nurse honey. Your nurse will be coming in soon. Bye!”

There was another liquid, brown, in a smaller bowl which he dared not try, and a glass of milk which tasted like milk anywhere, but he didn’t feel like finishing it. It was the first time he could remember having lost his appetite. He set his mind on finding the television instead. The room was even bigger without his mother and Dr. Stendhal in it. The other beds gleamed at him with their stiff white sheets and pillows. The floor (also green and white) was shiny too. Each of the six beds had a little swinging table and another table with a lamp beside it. There was a big, bright window with green drapes opened on either side of it, and a lingering Dr. Stendhal smell. No television.

“Hello.”

Luke turned back to the doorway. A real nurse stood there, holding a white torpedo upside-down in the air.

“Hi (cough). What’s that?”

“Turn around. This’ll be quick.”

“But —”

“No buts here, except one — ha, ha.”

She pulled down his pajama bottoms and dabbed his behind with something cool. Then the needle went in, and she kept it in for a very long time. He didn’t flinch, but refused to say anything to her, even when she asked if he needed anything.

“And oh,” she added as she was leaving, “the T.V.’s in the next room down the hall to the right. You may watch it until eight o’clock. Then it’s bed time for you.”

He did finally look up at her, but not for long. She was pretty.

The soreness from the torpedo shot was nearly gone as he approached the T.V. room. He was hardly coughing at all in this hospital, and wondered if he had to live there if he wanted to stop coughing for good. The hallway was cool and dim, but he noticed the familiar flickering very soon, and then the voice of Granny on The Beverly Hillbillies.

The room was much smaller than he’d imagined it. There were an old couch and a couple of hard-looking chairs, a round, gray rug, and some very beat-up wooden trucks. On the couch sat a fat woman beside a little girl who had a tube sticking out of her arm and leading up to a plastic bag on stilts. In one of the chairs, to the left of the couch, sat a mean-looking teenager with red marks all over his face and big feet. He too was in his pajamas, but no slippers.

“Hi,” Luke said, taking the other uncomfortable chair at first, then slipping down to the ugly rug.

The fat woman smiled at him and the mean kid said nothing. But Luke lost himself in the T.V. show, and even laughed a little, though this set him off, and he lapsed into a long coughing fit.

In what seemed to be less than a second that nurse appeared in the hallway, holding her hands on her hips and looking at him the way the school principal might.

“Why don’t you come back to the room,” she said. He knew it was not a request. He waved to the T.V. room people and the fat lady smiled again. The mean kid nodded. The Beverly Hillbillies were waving goodbye too, the way they always did at the end of the show.

“Do I need to have another shot?” he said to her.

“No, not tonight.”

She led him back into this room, where a nun stood waiting by his bed, holding a tall glass of some terrible, colorless liquid.

“Thank you, Sister,” the nurse said. “I’ll take that.”

The nun folded her arms and mumbled a short prayer. Then she blessed herself and touched Luke’s forehead with her old hand, before quietly leaving. He looked up at the nurse, who stood ready to tuck him in.

“Do I have to drink that now?”

“If you want to.”

“I think I’ll wait till later,” he added quickly, before she could change her mind.

“Good night, dear.”

She brought the cardboard sheets up to his chest and tucked them into the sides, raised the metal bars, and turned off the brightest light. He waited until she’d left before daring to look at the strange liquid, which made the glass sweat beads of water. It was funny to see a straw sticking out of all that medicine. Just as he was planning to carry it down to the bathroom and empty it into the toilet, a doctor passed by in the hallway, looking straight at him. They were everywhere, and they would know if he didn’t drink it.

In the next moment, then, he sat up, picked up the glass, closed his eyes, and tried to hold his breath while drinking, so that he wouldn’t taste it. But he was not very successful, and the soothing flavor of vanilla milk shake slid down his throat. He drank as much as he could before they could discover their mistake.

He opened his eyes to the morning, feeling that he might have slept and he might not have: the burning was in his throat, and he remembered someone giving him water once or twice during the night. That’s what he wanted now. He pulled off the stale covers; his feet hit the cold green floor. Cool air swirled in the hallway as he walked to the lavatory.

When he came back to his room he found it was no longer his. Someone was moving in beside him. The big drape was closed around the next bed, and he heard loud voices coming from behind it, using a lot of words he never heard before. But more interesting was the tray that was now by his bed. It had a small bowl of hot cereal on it, a glass of juice, and another small bowl with something brown and mushy in it.

The cereal was something his mother had made him before, only soggier. But he ate it, and drank the orange juice. The brown mush he left untouched.

“Hey, kiddo.”

He looked over; the curtain had been drawn, and all the people had left but the one lying in bed. It was a man, or at least a boy old enough to shave and maybe go to college. One of his legs was held up by strings in the air. It was covered in white strips, like a mummy.

“What happened to you?” Luke said.

“I had a little accident.”

“Wow. That’s neat. It looks like Halloween. Does it hurt?”

“It did. But now I don’t feel much of anything.” He pointed to the medicine bag on stilts that fed into his arm. “What are you in for?”

“I can’t breathe.”

“You’re fooling me.”

“It’s called brown key-hole azma. Yesterday they gave me a shot that was as long as your foot.”

“How long you stayin’?”

“Three days. My mom’s coming to visit though. Is your mom coming too?”

“She was just here.”

“How about your dad?”

The man put one arm behind his head and looked to the window:

“Him? Nah, you won’t be meeting him. He’s probably drunk right now.”

“My dad’s dead.”

He turned back to look at Luke.

“Oh? How?”

“I don’t know. He just died. When I was little.” Now Luke noticed the bruises on the man’s face, on the side that had been turned away from him. He didn’t say anything about them, because they looked scary. “What’s your name?” he finally said.

“Kevin.”

“Kevin?”

“Don’t wear it out.”

“Do you want to finish my breakfast?”

Kevin liked to sleep, Luke figured out, even more than eating, because he didn’t have anything to eat all morning. Any time Luke looked over he saw Kevin’s eyes were closed. But other things happened that day to keep Luke occupied.

There were more shots, of course. Big ones and little ones, all over his behind. But they were helping him to stop coughing, and most of the nurses were nice. One even smelled good. Dr. Stendhal came once, right after breakfast, with his usual cold hands and scary smell. He made Luke breathe deep and this made him cough—he knew it would—but the coughing didn’t last long. Luke asked if he could have a hot dog and this even got the old man to smile, though the answer was no.

Next came his mother, and she sat in the chair by his bed so they could play cards. He could tell she didn’t like the hospital either, because she spent a lot of time looking lost. She was never like that at home. They had lunch together (brown soup without noodles) and he found himself falling asleep as she rubbed his back. When he awoke from his nap she was gone, but she had left a package on his bed. Inside it was a set of matchbox cars, each in its own little yellow box. He immediately set to driving them along the hills and folds of his sheets.

An uncle of his stopped by on his way home from work: Uncle Norman. Uncle Norman had thin blonde hair and big glasses, and he brought Luke a Creepy Crawler set. It was one of the best gifts he’d ever gotten. Uncle Norman smiled a lot, and asked Luke everything there was to ask about his stay there, and how he felt, and whether or not the food was good. Luke was a little sad after he left.

Soon, though, his mother returned, this time with his sister and brother. He let his brother play with the cars but his sister just kept saying that she didn’t like it there and wanted to leave. She was still wearing her school clothes. When his mother stepped out to the hallway to talk with a nurse he told her about the milk shakes, and that he was already getting sick of them, there were so many.

“Get to sleep now, Luke. The doctor says you’re getting better. Tomorrow you’re coming home.” His mother gathered the children and gave him a little kiss. Then she was gone again.

Luke fell asleep coughing only once or twice, and wondering about a lot of things: about why the pea soup, why the funny roommate, why his mother didn’t keep the puppy his aunt had given them, and why he didn’t really miss home the first night but now he did. He awoke a couple of times that night, but not from coughing. He woke up hearing voices in the hall, trying to shut them out so he could go back to sleep.

Another time, when he awoke, he found that the bed opposite his was no longer empty. In it lay another sleeping boy, an old boy with a thick bandage around his head. He was sleeping very deeply, and around his bed sat a group of crying women. Luke drifted in and out of sleep for the rest of that night, hearing more voices, seeing white coats flashing by and standing around that bed, and watching the women hug one another. By morning light the boy and the women were gone. The bed lay there fresh and white, as if nothing had happened, though one of the chairs beside the bed was still crooked where the largest, babushka-wearing woman had been.

And that morning felt strange for Luke. It felt like a morning long ago for him, though he could not find it, it was so buried in his head. He barely ate his breakfast, which seemed the worst yet. Kevin had left his bed to go for a little ride in the rolling chair. Luke didn’t like being alone now; he didn’t like the bright light coming in through the window, or the way the sheets smelled, or even the Creepy Crawler set. He fell back into the bed and pulled the sheet and heavy blanket up to his neck, but this still did not take away his feeling. Where did that boy go? Why were those women crying? Did his mother come to get him? Now he had to cough, but he held it back. He lay very still and wouldn’t cough, no matter what.

Dr. Stendhal came, even colder than usual, and smelling worse than the sheets. He didn’t say very much to Luke, but told the nurse to write things down on a pad, which he then signed. After they left a nun came, this time a young smiling one, and she gave Luke a little coloring book with prayers in it. He was beginning to feel like getting out from under the covers now, and just then his mother came.

They passed the mill again on the way home, but there wasn’t much smoke coming out of it that day. Luke felt happy in the car with the sun warming him up through the window. But his mother was very quiet. Wasn’t she happy that he was coming home?

At home she had a surprise for him: the fried noodles-and-potato dough his grandmother sometimes made. It was his favorite thing. He asked if he had to go to school now and she said no. She said that when he went to school the next day he would be able to get up and walk to the water fountain in the hallway any time he wanted if he was coughing. She had spoken with Sister DeLellus about it.

Luke looked out the back window to their yard, which was all brown and orange-red now. Everything had died there. He smelled lunch cooking, and started thinking about the wonderful taste of pyzy in his mouth, as the furnace kicked on and his mother came up behind him to give him one, long hug.

“What’s wrong?” he said to her.

“Nothing,” she answered. “Just nothing.”

Ghost Tracks is copyright © 2017 Mark Saba. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.