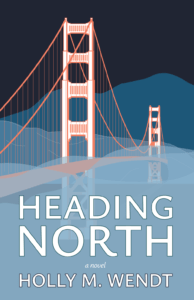

“A ‘tender hockey story’ might sound like a contradiction, but more precisely, it’s a rarity—and a gift. In Holly M. Wendt’s Heading North we follow one athlete whose life has been upended across a tragic, transformative season, but we also experience many moments of resiliency, generosity, and possibility within his web of teammates and supporters. Wendt’s narrative is ambitious in its scope, moving between Russian and US hockey cultures—not just comparing their approaches to play, but their capacity for inclusivity and care. In reading Heading North I was reminded of some of the ugly truths and history of a still too closed-minded sports culture, but was also shown the possibilities of a more capacious and kind future on and off the ice.” —Emily Nemens, author of The Cactus League

From the Publisher: “A young, talented Viktor Myrnikov is on the brink of realizing his lifelong dream of playing for the National Hockey League when a catastrophic plane crash kills all of his former Russian teammates, including his secret boyfriend, Nikolai, shattering his plans—and his heart. In this skillfully plotted debut, readers follow Viktor as he navigates cultural and sexual divides, the gamesmanship of damaged relationships, and the dark corners of professional sports. In prose that is as tender as it is tough, we witness a young man discovering inner resources he didn’t know he possessed as he struggles to find solace and respect in a world that has denied him of these things. An important discussion of today’s most pressing issues, and a tremendous achievement, Heading North is a most certainly a book for our times…”

More info About the Author: “Holly M. Wendt is Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at Lebanon Valley College. Wendt is a recipient of the Robert and Charlotte Baron Fellowship for Creative and Performing Artists from the American Antiquarian Society and fellowships from the Jentel Foundation and Hambidge Center. They have served as a Peter Taylor Fellow in fiction at the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. Their work has appeared in Passages North, Shenandoah, Four Way Review,Barrelhouse, Memorious, and elsewhere. A member of the Sport Literature Association, Holly is a former Baseball Prospectus contributor and contributing editor for The Classical. Their sports-based nonfiction has also appeared in Bodies Built for Game: The Prairie Schooner Anthology of Contemporary Sports Writing, The Rumpus, and Sport Literate.”

Author Site “In Heading North, Holly M. Wendt draws the reader into the world of professional hockey and into Viktor’s journey through the weight of silenced grief, through a sport’s rigid expectations of gender and sexuality, and through, despite everything, the glimmering hope of social and league-wide change. Wendt is a monumental talent of a writer, and I couldn’t wait to read this book. Sharply written and beautifully moving, this debut novel is an absolute must-read.” —Anne Valente, author of The Desert Sky Before Us

Note from Littsburgh: protagonist experiences homophobic slurs in this excerpt.

A lone firework flares red over Parov’s downtown glow, while Viktor Myrnikov and Nikolai Stepnov tighten the laces of their hockey skates on the snowy canal bank and step onto the narrow ice, sticks in hand. The New Year celebration means four days without games, two days when the Parov Iron Tigers won’t even practice, but here, now, they find ice.

A lone firework flares red over Parov’s downtown glow, while Viktor Myrnikov and Nikolai Stepnov tighten the laces of their hockey skates on the snowy canal bank and step onto the narrow ice, sticks in hand. The New Year celebration means four days without games, two days when the Parov Iron Tigers won’t even practice, but here, now, they find ice.

Each stride slices the quiet, a sound like silver, a sound like the fog pluming their mouths as they cross and re-cross their little rink. Viktor breathes in the cloud of Nikolai’s wake, then curls the puck away to circle one of their sneakers-and-snowbank goals.

The clear, hard tap of Nikolai’s stick on the ice—to me, to me—shudders through Viktor’s skate blades and up, up, coiling in his hands. The puck leaps toward the sound. Nikolai charges and their game begins in earnest: here is Viktor’s goal to defend, there his to attack.

Nikolai calls their game shinny, a word stolen from his father, who picked it up from a career played with Canadians all over the NHL. Whatever they call it, hockey is hockey: they will argue about whether the puck has crossed the invisible line or slipped wide, no arbitrator but the moonlight reflected by snow and whomever is more stubborn. That, too, is part of the joy.

Nikolai skates a little further and the ice hums, a thin crack somewhere between them, an easing settle. The canal’s meter of water is the least of their danger. While Nikolai passes to himself, canal-bank to skate blade, remnants of cheering arrive on the air—likely the end of the ice-carving contest—and under it, Viktor listens to Nikolai’s building speed. Nikolai skates right into him, his shoulder to Viktor’s chest, a shove and a promise as they scrabble, stick and stick. Nikolai leans, bites the earlobe under Viktor’s knit hat and kicks the puck between Viktor’s feet. He takes two swift strides and snaps his wrists; a spray of snow flies up from the goal-bank. Viktor whistles the interference as Nikolai laughs over the pop and glitter of another firework, then two, the slurring noise of song in the distance. This is what they’ve skipped: the too-easy, too-careless affection of being drunk, the raucous claustrophobia of the city’s celebration. Viktor shakes off a chill and bends into their imaginary faceoff circle and tries to think of hockey, only hockey, but there is Nikolai across from him, level with his eyes.

Nikolai wins the draw, and when he feints left a third time, Viktor pulls the puck to his own blade. Draggy seams of snow ripple the canal ice, but the air is fast, dry and snapping—clean enough that Viktor can imagine the iron in his blood calling north and north toward the goal, always hockey’s pole star. He flicks the puck over the line even as Nikolai’s hip catches his. Nikolai spins away and back; even if they play against each other tonight, success is always something to celebrate. He raises his hand to slap Viktor’s. Viktor stretches up, lifts his hand full-height, so Nikolai has to jump. An excuse to catch and be caught.

“Dick,” Nikolai says, laughing. He rests the padded fist of his glove under Viktor’s jaw, brushes an uppercut softly from chin to cheek. “The NHL is going to love you.” As soon as it knows you exist lingers unspoken.

Everyone knows who Nikolai is. He is Kirill Stepnov’s son. Knowing Nikolai has been good for Viktor’s career; the scouts who come to see him can’t help but see Viktor, whose passes are so often the launch point of Nikolai’s attack. The trouble is that it will end both their careers, Viktor is certain, if anyone discovers all the ways they know each other. The trouble is, with Nikolai, someone is always looking.

As the night slips on, the game collapses. When Nikolai tries to dart past, Viktor bear-hugs him, stands up straight so Nikolai’s skates dangle and their joint breath eddies. Nikolai’s knees hitch up on his waist, just for a moment, and then they are separate again, battling for the puck. Viktor wins this one and shoots. He is digging it from the snowbank again when the light changes, doubled and tinted, swirling red and blue. A smaller, brighter beam cuts across them both. At its end, a policeman.

“Get off the canal,” he barks.

Nikolai pulls off his hat, skates right up to the man. Viktor tries to remember the timing. When did the light change? How long might that man have been standing there in the dark? How far and how fast would they have to skate to be lost in shadow?

Nikolai says, “Just getting a little skate in, officer. Have to stay sharp if we’re going to beat Penza.” He beckons Viktor closer.

The officer laughs when Viktor comes into the flashlight’s beam, unmistakable as he is—more than two meters tall and missing a front tooth. Viktor can’t decide if he recognizes the officer. A lot of the police come to Iron Tigers games. A few used to play. He can’t say how many were involved in the raid of an underground nightclub six months ago, too, when four men were arrested. One died in prison. Two are still there. Drugs, people said, but Viktor saw the photos: all men in the background. Two, out of focus, clinging hand in hand.

Viktor and Nikolai get a wagging finger. “Enjoy a night off. Go join the party. Find a snowmaiden or two.” The rock of his gun-belted hips could be about sex or dancing, and Nikolai smirks like he’s supposed to. The officer waits until they gather up their sneakers, swap them for their skates, and climb back up the bank. Something crackles on his radio. “Remember,” he says, “go have fun. Don’t be here.” He calls out good luck for their next game as he drives away. As soon as the taillights disappear, Nikolai takes Viktor’s hand and lifts a bared middle finger into the exhaust fug. The pulses in their thumbs echo one to the other, a feeling so firm Viktor swears he can see it, even though the flashlight and the light bar have made him night-blind. From the road, their makeshift rink is murky, distant. The dark becomes smaller, the city-haze brighter, closer, louder, worse. But Nikolai is still here, the way he was after that fourth day of training camp, a scant four months ago.

A few teammates had already decided to hate Nikolai Stepnov on principle, born with gilded skates on his feet. A few others tried to impress him, as though that would get them two steps closer to his father, the hero of the Nagano Olympics.

Viktor simply kept his head down off the ice. If his eyes were on his stick tape or skate laces, he couldn’t look at Nikolai at all, couldn’t attract a moment of notice for anything but his play, and no one could see how his mouth tightened when some teammates talked, and if he seldom said anything at all, no one heard when he went quiet altogether, when faggot this and homo that jagged the air. No one paid attention to Viktor when Nikolai was there, elbow propped on the wall or even a teammate’s shoulder, like the third-line center was furniture. On that fourth day, Tomas, angling to be allowed to drive Nikolai’s Mercedes, asked to use some of Nikolai’s hair gel.

Sandr Dudin, lip curled like he smelled spoiled meat, said, “What a bunch of queers.”

Tomas scraped his dark hair back. “Ask your mom—”

“Fuck off.” Sandr threw a wadded sock that bounced against Tomas’s open mouth. Nikolai threw one of his own at Sandr’s cheek. “What the hell was that for?” Sandr said.

“Your goddamn language.” Nikolai pulled on his shirt, shook his pale hair into place.

“Not in California anymore.” Sandr squared his shoulders, and Viktor wondered, as though outside of his own head, what he would do if Sandr took a swing at Nikolai Stepnov. The coaches’ offices had been long dark.

But Nikolai sneered. “Obviously.” The jut of his chin aimed at the gray concrete walls, the two standing sinks, the rust biting the paint, the flickering bulb in the shower, and then Sandr himself, whose younger brother had been drafted by Seattle. Those scouts did not come to see Sandr play.

“Fuck you, golden boy.” The heavy doors slammed behind Sandr. Half a dozen others followed, including Thomas, still raking at his hair.

Nikolai’s hands moved slowly on his shoe laces, and Viktor dithered over the stick he was retaping. He deliberately did not look up when Grisha, one of the four teammates Viktor shared an apartment with, tried to catch his attention. Grisha left without trying any harder. By the time the black tape was aligned exactly so, Viktor and Nikolai were the only two left.

“Nice shoes,” was all he could think to say, but it was true. New Jordans, real ones, parrot blue, worth what Viktor made in a month.

“Thanks,” Nikolai said. He pulled his feet beneath the bench. Under his tight thermal, his chest rose and fell like they’d just finished practice; he glanced at the door, seemed to brace as Viktor finally looked Nikolai in the eye.

He had to look down to do it, which meant Nikolai had to look up. A pipe clanged and Nikolai flinched, the empty room echoing. Viktor slouched, tried to make himself smaller. If he could just say thank you for what you said, Nikolai wouldn’t be sitting like that. Wouldn’t look afraid. But Viktor was fearful, too, and there were so many things he didn’t know how to say. What he could do was jingle his keys, step a little farther back. “You hungry? There’s a good place near the movie theater.”

Nikolai’s green eyes slanted toward him. “You’re actually serious?”

“If you’re not too good for noodles. They have those in California, right?” He grinned at Nikolai’s extended middle finger, and then Nikolai was almost smiling, too.

That day feels like a lifetime ago. Or tonight is someone else’s life, and someone else’s body sits in the passenger seat of Nikolai’s car on a dirt road six kilometers from the city limits, but these can only be Viktor’s knees bent high by the dashboard, Viktor leaning over the center console as the seconds tick down to midnight. Only Viktor who can’t keep his eyes closed as they kiss. This is the most public they’ve ever been. From the darkness beyond Nikolai’s shoulder, he keeps imagining another flashlight beam, another and another.

The phone buzzing in Nikolai’s pocket startles like relief. Kirill. It’s always Kirill, at this time, on this day, no matter what. Seven years ago, Kirill called Nikolai from the bench, in the second period of a game, during his second season in Colorado, the year after the Avalanche won the Stanley Cup.

Viktor had read about the infamous phone call in the papers long before he knew Nikolai. He read everything about Kirill Stepnov. Everyone did. The North American media skewered Kirill for his lack of focus, no matter that he scored two goals in the game. The Russian media defended him—the NHL cared nothing for the bond between father and son, the rigors of keeping family at a distance, the importance of this holiday of all holidays to Russian players. The Moscow papers willfully omitted the fact that no Russian coach would tolerate such a thing, either. Kirill’s first coach would have skated Kirill until he coughed blood and then dismissed him from the team outright. The Parov Iron Tigers are not permitted to have their mobile phones in the arena at all.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.