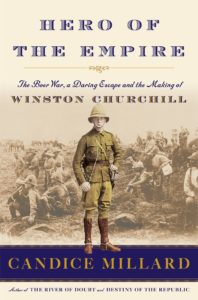

Candice Millard, the award-winning and New York Times bestselling author of Destiny of the Republic and The River of Doubt, is visiting Pittsburgh on Wednesday, September 21st as part of Pittsburgh Arts and Lectures’ New and Noted series!

Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill, Millard’s latest book, “delivers a thrilling narrative of Winston Churchill’s extraordinary and little-known exploits during the Boer War and the lessons he learned that would profoundly affect 20th century history.”

From the Publisher: “Churchill arrived in South Africa in 1899, valet and crates of vintage wine in tow, there to cover the brutal colonial war the British were fighting with Boer rebels. But just two weeks after his arrival, the soldiers he was accompanying on an armored train were ambushed, and Churchill was taken prisoner. Remarkably, he pulled off a daring escape–but then had to traverse hundreds of miles of enemy territory, alone, with nothing but a crumpled wad of cash, four slabs of chocolate, and his wits to guide him.

The story of his escape is incredible enough, but then Churchill enlisted, returned to South Africa, fought in several battles, and ultimately liberated the men with whom he had been imprisoned.

Churchill would later remark that this period, ‘could I have seen my future, was to lay the foundations of my later life.’ Millard spins an epic story of bravery, savagery, and chance encounters with a cast of historical characters—including Rudyard Kipling, Lord Kitchener, and Mohandas Gandhi—with whom he would later share the world stage. But Hero of the Empire is more than an adventure story, for the lessons Churchill took from the Boer War would profoundly affect 20th century history…”

Crouching in darkness outside the prison fence in wartime southern Africa, Winston Churchill could still hear the voices of the guards on the other side. Seizing his chance an hour earlier, the 25-year-old had scaled the high, corrugated-iron paling that enclosed the prison yard. But now he was trapped in a new dilemma. He could not remain where he was. At any moment, he could be discovered and shot by the guards or by the soldiers who patrolled the dark, surrounding streets of Pretoria, the capital of the enemy Boer Republic. Yet neither could he run. His hopes for survival depended on two other prisoners, who were still inside the wall. In the long minutes since he had dropped down into the darkness, they had not appeared.

Crouching in darkness outside the prison fence in wartime southern Africa, Winston Churchill could still hear the voices of the guards on the other side. Seizing his chance an hour earlier, the 25-year-old had scaled the high, corrugated-iron paling that enclosed the prison yard. But now he was trapped in a new dilemma. He could not remain where he was. At any moment, he could be discovered and shot by the guards or by the soldiers who patrolled the dark, surrounding streets of Pretoria, the capital of the enemy Boer Republic. Yet neither could he run. His hopes for survival depended on two other prisoners, who were still inside the wall. In the long minutes since he had dropped down into the darkness, they had not appeared.

From the moment he had been taken as a prisoner of war, Churchill had dreamed of reclaiming his freedom, hatching scheme after scheme, each more elaborate than the last. In the end, however, the plan that had actually brought him over the fence was not his own. The two other English prisoners had plotted the escape, and agreed only with great reluctance to bring him along. They also carried the provisions that were supposed to sustain all three of them as they tried to cross nearly three hundred miles of enemy territory. Unable even to climb back into his hated captivity, Churchill found himself alone, hiding in the low, ragged shrubs that lined the fence, with no idea what to do next.

Although he was still a very young man, Churchill was no stranger to situations of great personal peril. He had already taken part in four wars on three different continents, and had come close to death in each one. He had felt bullets whistling by his head in Cuba, seen friends hacked to death in British India, been separated from his regiment in the deserts of the Sudan and, just a month earlier, in November 1899, at the start of the Boer War, led the resistance against a devastating attack on an armored train. Five men had died in that attack, blown to pieces by shells and a deafening barrage of bullets, many more had been horribly wounded, and Churchill had barely escaped with his life. To his fury and deep frustration, however, he had not eluded capture. He, along with dozens of British officers and soldiers, had been taken prisoner by the Boers—the tough, largely Dutch-speaking settlers who had been living in southern Africa for centuries and were not about to let the British Empire take their land without a fight.

When the Boers had realized that they had captured the son of Lord Randolph Churchill, a former Chancellor of the Exchequer and a member of the highest ranks of the British aristocracy, they had been thrilled. Churchill had been quickly transported to a POW camp in Pretoria, the Boer capital, where he had been imprisoned with about a hundred other men. Since that day, he had been able to think of nothing but escape, and returning to the war.

The Boer War had turned out to be far more difficult and more devastating than the amusing colonial war the British had expected. Their army, one of the most admired and feared fighting forces in the world, was astonished to find itself struggling to hold its own against a little-known republic on a continent that most Europeans considered to be theirs for the taking. Already, the British had learned more from this war than almost any other. Slowly, they were realizing that they had entered a new age of warfare. The days of gallant young soldiers wearing bright red coats had suddenly disappeared, leaving the vaunted British army to face an invisible enemy with weapons so powerful they could wreak carnage without ever getting close enough to look their victims in the eye.

Long before it was over, the war would also change the empire in another, equally indelible way: It would bring to the attention of a rapt British public a young man named Winston Churchill. Although he had tried again and again, in war after war, to win glory, Churchill had returned home every time without the medals that mattered, no more distinguished or famous than he had been when he set out. The Boer War, he believed, was his best chance to change that, to prove that he was not just the son of a famous man. He was special, even extraordinary, and he was meant not just to fight for his country but to one day lead it. Although he believed this without question, he still had to convince everyone else, something he would never be able to do from a POW camp in Pretoria.

When Churchill had scrambled over the prison fence, seizing his chance after a nearby guard had turned his back, he felt elated. Now, as he kneeled in the shrubs just outside, waiting helplessly for the other men, his desperation mounted with each passing minute. Finally, he heard a British voice. Churchill realized with a surge of relief that it was one of his co-conspirators. “It’s all up,” the man whispered. The guard was suspicious, watching their every move. They could not get out. “Can you get back in?” the other prisoner asked.

Both men knew the answer. As they stood on opposite sides of the fence, one still in captivity, the other achingly close to freedom, it was painfully apparent that Churchill could not undo what had already been done. It would have been impossible for him to climb back into the prison enclosure without being caught, and the punishment for his escape would have been immediate and possibly fatal.

In all the time he had spent thinking about his escape since arriving in Pretoria, the one scenario that Churchill had not envisioned was crossing enemy territory alone without companions or provisions of any kind. He didn’t have a weapon, a map, a compass, or, aside from a few bars of chocolate in his pocket, any food. He didn’t speak the language, either that of the Boers or the Africans. Beyond the vaguest of outlines, he didn’t even have a plan—just the unshakeable conviction that he was destined for greatness.

Excerpted from Hero of the Empire by Candice Millard Copyright © 2016 by Candice Millard. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.