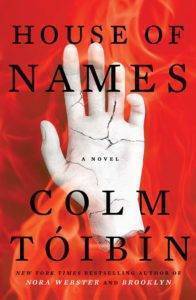

Award-winning and critically acclaimed Colm Tóibín is the author of seven novels including The Master, Brooklyn, The Testament of Mary, and Nora Webster, as well as two story collections. The film adaptation of Brooklyn received three Academy Award nominations including Best Picture.

Don’t miss out: Tóibín will be visiting Pittsburgh Arts and Lectures on June 20th!

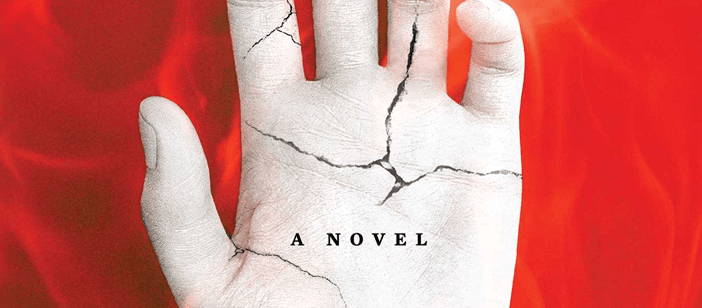

In House of Names, Tóibín masterfully retells the myth of Clytemnestra, Agamemnon, and their three children. In the ancient story, Agamemnon, desperate for wind so he can sail to battle, sacrifices his oldest daughter. His wife, Clytemnestra, enraged and betrayed, plots her revenge and when Agamemnon returns triumphant from war, Clytemnestra murders him. In turn, Orestes, her only son, spurred to action by his sister Electra, murders Clytemnestra.

The story of this unblessed family gains new nuance and richness in Tóibín’s hands including an illuminating focus on Orestes. House of Names is about a fierce and ferociously dramatic family, and who is better on families, in all their complexity, than Colm Tóibín?

Clytemnestra

I have been acquainted with the smell of death. The sickly, sugary smell that wafted in the wind towards the rooms in this palace. It is easy now for me to feel peaceful and content. I spend my morning looking at the sky and the changing light. The birdsong begins to rise as the world fills with its own pleasures and then, as day wanes, the sound too wanes and fades. I watch as the shadows lengthen. So much has slipped away, but the smell of death lingers. Maybe the smell has entered my body and been welcomed there like an old friend come to visit. The smell of fear and panic. The smell is here like the very air is here; it returns in the same way as light in the morning returns. It is my constant companion; it has put life into my eyes, eyes that grew dull with waiting, but are not dull now, eyes that are alive now with brightness.

I have been acquainted with the smell of death. The sickly, sugary smell that wafted in the wind towards the rooms in this palace. It is easy now for me to feel peaceful and content. I spend my morning looking at the sky and the changing light. The birdsong begins to rise as the world fills with its own pleasures and then, as day wanes, the sound too wanes and fades. I watch as the shadows lengthen. So much has slipped away, but the smell of death lingers. Maybe the smell has entered my body and been welcomed there like an old friend come to visit. The smell of fear and panic. The smell is here like the very air is here; it returns in the same way as light in the morning returns. It is my constant companion; it has put life into my eyes, eyes that grew dull with waiting, but are not dull now, eyes that are alive now with brightness.

I gave orders that the bodies should remain in the open under the sun a day or two until the sweetness gave way to stench. And I liked the flies that came, their little bodies perplexed and brave, buzzing after their feast, upset by the continuing hunger they felt in themselves, a hunger I had come to know too and had come to appreciate.

We are all hungry now. Food merely whets our appetite, it sharpens our teeth; meat makes us ravenous for more meat, as death is ravenous for more death. Murder makes us ravenous, fills the soul with satisfaction that is fierce and then luscious enough to create a taste for further satisfaction.

A knife piercing the soft flesh under the ear, with intimacy and precision, and then moving across the throat as soundlessly as the sun moves across the sky, but with greater speed and zeal, and then his dark blood flowing with the same inevitable hush as dark night falls on familiar things.

They cut her hair before they dragged her to the place of sacrifice. My daughter had her hands tied tight behind her back, the skin on the wrists raw with the ropes, and her ankles bound. Her mouth was gagged to stop her cursing her father, her cowardly, two- tongued father. Nonetheless, her muffled screams were heard when she finally realized that her father really did mean to murder her, that he did mean to sacrifice her life for his army. They had cropped her hair with haste and carelessness; one of the women managed to cut into the skin around my daughter’s skull with a rusty blade, and when Iphigenia began her curse, that is when a man tied an old cloth around her mouth so that her words could not be heard. I am proud that she never ceased to struggle, that never once, not for one second, despite the ingratiating speech she had made, did she accept her fate. She did not give up trying to loosen the twine around her ankles or the ropes around her wrists so that she could get away from them. Or stop trying to curse her father so that he would feel the weight of her contempt.

No one is willing now to repeat the words she spoke in the moments before they muffled her voice, but I know what those words were. I taught them to her. They were words I made up to shrivel her father and his followers, with their foolish aims, they were words that announced what would happen to him and those around him once the news spread of how they dragged our daughter, the proud and beautiful Iphigenia, to that place, how they pulled her through the dust to sacrifice her so they might prevail in their war. In that last second as she lived, I am told she screamed aloud so that her voice pierced the hearts of those who heard her.

Her screams as they murdered her were replaced by silence and by scheming when Agamemnon, her father, returned and I fooled him into thinking that I would not retaliate. I waited and I watched for signs, and smiled and opened my arms to him, and I had a table here prepared with food. Food for the fool! I was wearing the special scent that excited him. Scent for the fool!

I was ready as he was not, the hero home in glorious victory, the blood of his daughter on his hands, but his hands washed now as though free of all stain, his hands white, his arms out- stretched to embrace his friends, his face all smiles, the great soldier who would soon, he believed, hold up a cup in cele- bration and put rich food into his mouth. His gaping mouth! Relieved that he was home!

I saw his hands clench in sudden pain, clench in the grim, shocked knowledge that at last it had come to him, and in his own palace, and in the slack time when he was sure he would enjoy the old stone bath and the ease to be found there.

That was what inspired him to go on, he said, the thought that this was waiting for him, healing water and spices and soft, clean clothes and familiar air and sounds. He was like a lion as he laid his muzzle down, his roaring all done, his body limp, and all thought of danger far from his mind.

I smiled and said that, yes, I too had thought of the welcome I would make for him. He had filled my waking life and my dreams, I told him. I had dreamed of him rising all cleansed from the perfumed water of the bath. I told him his bath was being prepared as the food was being cooked, as the table was being laid, and as his friends were gathering. And he must go there now, I said, he must go to the bath. He must bathe, bathe in the relief of being home. Yes, home. That is where the lion came. I knew what to do with the lion once he came home.

I had spies to tell me when he would come back. Men lit each fire that gave the news to farther hills where other men lit fires to alert me. It was the fire that brought the news, not the gods. Among the gods now there is no one who offers me assistance or oversees my actions or knows my mind. There is no one among the gods to whom I appeal. I live alone in the shivering, solitary knowledge that the time of the gods has passed.

I am praying to no gods. I am alone among those here because I do not pray and will not pray again. Instead, I will speak in ordinary whispers. I will speak in words that come from the world, and those words will be filled with regret for what has been lost. I will make sounds like prayers, but prayers that have no source and no destination, not even a human one, since my daughter is dead and cannot hear.

I know as no one else knows that the gods are distant, they have other concerns. They care about human desires and antics in the same way that I care about the leaves of a tree. I know the leaves are there, they wither and grow again and wither, as people come and live and then are replaced by others like them. There is nothing I can do to help them or prevent their withering. I do not deal with their desires.

I wish now to stand here and laugh. Hear me tittering and then howling with mirth at the idea that the gods allowed my husband to win his war, that they inspired every plan he worked out and every move he made, that they knew his cloudy moods in the morning and the strange and silly exhilaration he could exude at night, that they listened to his implorings and discussed them in their godly homes, that they watched the murder of my daughter with approval.

The bargain was simple, or so he believed, or so his troops believed. Kill the innocent girl in return for a change in the wind. Take her out of the world, use a knife on her flesh to ensure that she would never again walk into a room or wake in the morning. Deprive the world of her grace. And as a reward, the gods would make the wind blow in her father’s favor on the day he needed wind for his sails. They would hush the wind on the other days when his enemies needed it. The gods would make his men alert and brave and fill his enemies with fear. The gods would strengthen his swords and make them swift and sharp.

When he was alive, he and the men around him believed that the gods followed their fates and cared about them. Each of them. But I will say now that they did not, they do not. Our appeal to the gods is the same as the appeal a star makes in the sky above us before it falls, it is a sound we cannot hear, a sound to which, even if we did hear it, we would be fully indifferent.

The gods have their own unearthly concerns, unimagined by us. They barely know we are alive. For them, if they were to hear of us, we would be like the mild sound of wind in the trees, a distant, unpersistent, rustling sound.

I know that it was not always thus. There was a time when the gods came in the morning to wake us, when they combed our hair and filled our mouths with the sweetness of speech and listened to our desires and tried to fulfill them for us, when they knew our minds and when they could send us signs. Not long ago, within our memories, the crying women could be heard in the night in the time before death came. It was a way of calling the dying home, hastening their flight, softening their wavering journey to the place of rest. My husband was with me in the days before my mother died, and we both heard it, and my mother heard it too and it comforted her that death was ready to lure her with its cries.

That noise has stopped. There is no more crying like the wind. The dead fade in their own time. No one helps them, no one notices except those who have been close to them during their short spell in the world. As they fade from the earth, the gods do not hover over with their haunting, whistling sound. I notice it here, the silence around death. They have departed, the ones who oversaw death. They have gone and they will not be back.

My husband was lucky with the wind, that was all, and lucky his men were brave, and lucky that he prevailed. It could easily have been otherwise. He did not need to sacrifice our daughter to the gods.

My nurse was with me from the time I was born. In her last days, we did not believe that she was dying. I sat with her and we talked. If there had been the slightest sound of wailing, we would have heard. There was nothing, no sound to accompany her towards death. There was silence, or the usual noises from the kitchen, or the barking of dogs. And then she died, then she stopped breathing. It was over for her.

I went out and looked at the sky. And all I had then to help me was the leftover language of prayer. What had once been powerful and added meaning to everything was now deso- late, strange, with its own sad, brittle power, with its memory, locked in its rhythms, of a vivid past when our words rose up and found completion. Now our words are trapped in time, they are filled with limits, they are mere distractions; they are as fleeting and monotonous as breath. They keep us alive, and maybe that is something, at least for the moment, for which we should be grateful. There is nothing else…

This excerpt of House of Names: A Novel by Colm Tóibín is published here courtesy of the publisher. It should not be reprinted without permission.