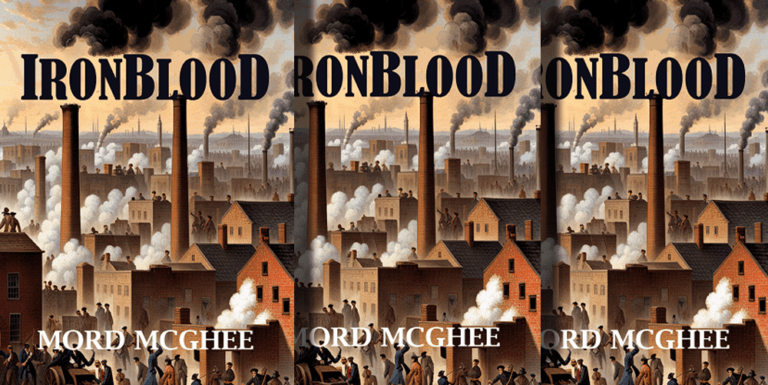

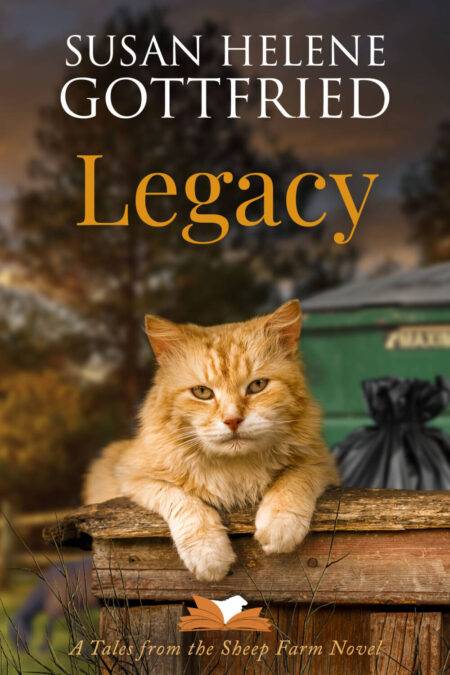

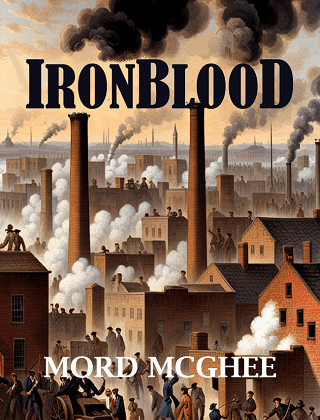

From the Publisher: “Ironblood is a historical saga exploring the raw and complicated story of America’s industrial legacy, which gives voice to humanity’s worst fears yet displays our greatest hopes. A story told through the eyes of characters from various cultures and countries after the American Civil War, pitted against one another amidst the rise of steelmaking empires.

Pearl, a recently freed slaves formerly living on the run. Earl, who falls in love with her at first sight. Hans, a recent immigrant from Germany, with a murderous gang on his tail. When their mutual friend dies in the Battle of Gettysburg, Earl and Hans become owners of an ironworks in Homestead, Pennsylvania.

Floods. Strikes. Massacres. Social upheaval, Ironblood shows the experiences of America’s industrial history and the struggles between labor and management. Superstitions and dark secrets create a backdrop of industrial smoke and flame boiling over. At times hopeful, at times tumultuous, this is a tragic and wondrous voyage of self-sacrifice, betrayal, and unbreakable love.”

More info About the Author: “Mord McGhee is an award-winning author of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and literary fiction, based in North Myrtle Beach (Little River), South Carolina and Pittsburgh (Moon Township), Pennsylvania in the United States of America. His fiction is unique and has been dubbed “Outlaw Traditionalist” which is not easily put down, once begun. His latest novel IRONBLOOD (Golden Storyline Books, London) was released in November with paperback, hardback, and audio books upcoming…”

Author Site

Prologue

Prologue

June, modern day.

Clayton House, Pennsylvania

“This way please,” said the tour guide, and the group tightened around her. The room had a solemn mood. Art on the wall was plentiful and mostly of portraits of the family who once resided there long ago. The faces were unexpressive, painted to show the seriousness of their legacy. They’d come a terrific way to live in the mansion called Clayton House. The furniture was art, the walls art, all sharing one theme: red roses.

The tour guide drew the group’s attention to a glass case in the middle of the room, where beneath it lay a simple metal flower. A child muttered something about Belle, but the tour guide ignored her and told them, “As you know by their famous collection, the Fricks were avid procurers of artwork from around the world. This is an iron rose thought to have been crafted in Austria, circa 1850. It was a favorite of theirs, and mine. There is even a special tour of a secret cemetery on the property, offered once every few years by the grandson of Matthias Butler, of whom even we learn surprise after surprise about the Frick and Carnegie story.”

Those present to bear witness to old Allegheny City’s most prominent clan went in for a closer look. One pressed his nose right up to the protective cover. “It’s not very pretty,” he said, disinterestedly. “Like a kid made it almost.”

“Sadly,” the tour guide said, “other than a brief note of its acquisition in 1953, we know little about it. There is some connection to their beloved daughter Rosebud, and scholars think Mister had it commissioned for her passing, while others suspect it was created by the ghosts of the missing ironworkers.”

“Missing ironworkers!” a man said.

“That’s our evening tour should you wish to learn more,” said the tour guide.

“Who did make it?” a child asked.

“They don’t know,” the child’s parent said. The parents guided the child out of the room, away from the display. While the group moved along through the mansion, the parent spoke softly to the tour guide, “Sorry about that.”

“Don’t sweat it,” the tour guide replied, courteous smile intact. “We love children here at the museum. We feel their presence warms the memories of the house somehow. Wakes it up, you know?”

“Those ghosts,” the man said. “Who are the missing ironworkers? I never heard of them.”

“That really is a different tour entirely,” said the guide. “But many immigrants from Europe at the time had no family, no connections, couldn’t read or write, and it’s a fact that some simply vanished. The steel mill in Homestead is no exception. This way if you will.”

“Wait. About the rose,” said a woman who was actively snuggling the little one under both arms. “Is it original, from the New York collection?”

“Not at all,” the guide returned. Then she waved the group ahead and announced, “Next, we come to the guest’s foyer. An entry where visitors could present their invitation cards and await whatever business had brough them here. My own great, great grandmother worked for them, right in this room.”

“What’s her name?” a child asked.

“Mary McBride,” the guide replied.

“Is she still here?” the child asked, eyes wide.

“It was a very long time ago,” the guide said.

Behind them, a distant memory stirred within the iron rose.

The rose had witnessed much during its existence. From a humble origin in the mountains of Eastern Europe, all the way to a pool of blood on the floor where the most powerful leader of industry desperately fought for his life. Froth flying from lips. Eyes burning with rage. Yes, the rose had seen it all.

Chapter One

April 11, 1836

Strange fruit

In the spring of 1836 Earl was one dreaming boy with a slovenly and sleepy way about him which drew attention from adults. Often not the attention he intended either. The place his Aunt Bertha had left him was the sort which made him fearful, always outnumbered by bigger and meaner kids. Although, without anything in the way of prospects, Earl made do.

He had a great big heart, the power which kept him alive in tense situations. Though he knew the date not, it was early April. He Earl walked along the new road behind Sullivan’s pit. He sang softly. “The road leads on the fox and dove so clever. Dance away by crack of day before the farmer heats and haver.”

A loud crash broke the quiet surroundings, and along with the racket came a slew of angry voices. Earl ducked out of sight, slid beneath the bushes along the row separating white folk homes from the Black. There he saw them, marching down Lane. Incalculable rows of screwed faces, shouting as they pumped torches, clubs, ropes, and axes into the air. Earl trembled as the mob shouted, “Our jobs! Our jobs!” A howl rose above the rest and said, “Black code!” Later, it was the sound of breaking glass he remembered most of all. The mob surged ahead with cries of “sell them down river” and “enforce Black laws!” and the day had grown suddenly terrifying in the lower west end of Cincinnati.

A torch flew from the crowd, sailing end over end through an open window. A yellow flash preceded the quick spread of flames. Out the sill, up the wall to the roof, smoke wafting as the wings of birds. The house groaned, belched, collapsed. The mob bayed communal frenzy.

“No,” Earl said, at once covering his mouth with his palm.

It was the sheriff who turned. Earl hid his face with his arm and next he targeted another building, plowed into its face. When Earl found the courage to look again, he found himself looking back at Sheriff Birney. The man said nothing but simply stared at Earl with puffy pink cheeks as the throng boomed and dragged John Harrison out of his own door then cast him to the ground in their midst. The mob grew quiet as Mr. Harrison knuckled the dirt, pushed himself to his feet. A hound snapped its jaws and Sheriff Birney spoke at last.

“John Harrison,” he said. “We charge you with being abolitionist scum and hereby sentence you to Hell!”

Mr. Harrison swatted with his hands as torches poked and prodded. Burning tips brushed his skin, and a club fell across his brow which sent him to one knee. The crackling of the pine tar became louder than life itself, and more glass breaking in the distance. Earl held his breath. The sheriff stepped forward, dropped a noose around Mr. Harrison’s neck. The sheriff tugged the rope and passed it to another, then pointed straight at Earl.

A woman shouted, “Get that little shit!”

Mr. Harrison met Earl’s eyes and said, “Run, boy.”

Too late. Fists grabbed him, yanking his head back, ripping at his clothing, pinning his hands. Pungent smells filled Earl’s nose. Sweat, whiskey, pine tar, smoke. A rope clamped around his throat. A knee pressed into his back, and he struggled to breathe. Ahead, two men clubbed Mr. Harrison until his flesh bulged purple. Earl closed his eyes, a silent scream upon his lips.

When they opened again, added buildings burst into flame. Earl could do nothing as the sheriff and his deputy hoisted Mr. Harrison off the ground upon a limb of a tree outside his own butcher shop. His legs kicked weakly for a moment, then sagged unmoving in front of the sign which read: Black owned – Whites served first.

“His turn,” said Sheriff Birney, waving a hand at Earl.

A white kid Earl recognized stepped in front of the sheriff. Earl mouthed the word “help.”

Sheriff Birney swatted the boy aside, “Get the fuck out of here, Daniel.”

“No,” said the kid. “Wait!” He looked at Earl.

“Well?” the sheriff said. “What do you want to say?”

Daniel drew back and kicked Earl in the crotch. Earl never found the breath he desperately needed to stay conscious and instead the world darkened. When he came to at last, a fog enveloped his mind. Was he alive or dead? Was it real or a dream? To Earl the riot was little more than a blur along with that horrific memory of poor Mr. Harrison.

Earl opened his eyes under the light of the sun. He was on a boat with a throbbing headache. His neck felt raw as he rolled over onto his back. He heard the rush of running water and he smelled a strong fishiness. Wood wax too, all blended. A gray bird with a funny blue beak took flight nearby. Earl looked up at the sound of approaching footsteps to see an elderly man with a bushy beard and bald scalp. Next to him was a young man with red skin, a black braid of hair, and a toothless smile.

“What’s your name?” asked the elderly man.

Earl said nothing.

The old man grunted, said, “Do have a name, don’t you?”

“Could be deaf and dumb,” said the boy with the braid.

The bald man’s white beard blew in the wind, and he said, “Easy, Ches. Give him a chance to find his wits. Had a heck of a night.”

“Earl.”

The elderly man grinned. “Sometimes,” he said, “the Lord wants you somewhere, Earl, and don’t tell you what for.” With this simple sentiment, Earl was reborn.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.