Dr. Madhu Bazaz Wangu is a Wexford, Pennsylvania-based author and the founder of Mindful Writers Group, in which novice and professional writers meditate and write together to improve focus, remove blocks and increase creative flow. Wangu has written extensively about Buddhist and Hindu art, and her published fiction includes Chance Meetings (2015), An Immigrant Wife: Her Spiritual Journey (2016) — a winner in the Women’s Fiction and Spirituality categories in the 2017 National Indie Excellence Awards and a finalist in Next Generation Indie Book Awards — and The Last Suttee (2017).

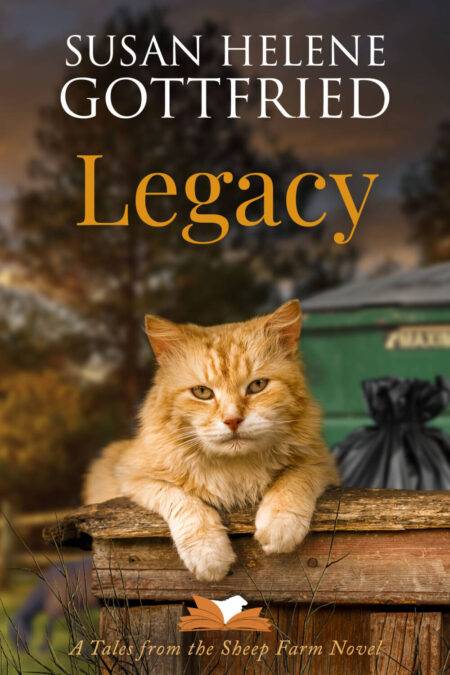

From the publisher: “The Last Suttee, is a novel about a woman’s struggle to put an end to the ancient ritual, suttee, meant for a widow to self-immolate on the funeral pyre of her husband. Kumud Kuthiyala has worked hard to put her early life in Neela Nagar behind her. As director of an all-girl orphanage in metropolitan Ambayu, she has become a warrior for women’s education and equal rights. With the help of her love, Dr. Shekhar Roy, she is vigilant in protecting her charges from outdated customs that victimize girls and women. Yet, despite her many successes, her past still haunts her…”

FOREWORD

On the morning of September 5, 1987, I was going through the Hillman Library card catalogue at the University of Pittsburgh when a friend stopped by. She told me something I would never forget. She said that an eighteen-year-old Indian woman, named Roop Kanwar, had immolated herself on the pyre of her dead husband. I was dumbfounded. Suttee in the twentieth century? It couldn’t be. But The New York Times confirmed the news. The ritual, known as suttee, was witnessed by the townspeople and thousands more came to see it from nearby villages and towns. When the news was leaked the following day, the town was swarmed for days by Indian and international journalists. I was stunned and speechless, my legs laden with lead. At that frozen moment, the seed for this book was planted.

On the morning of September 5, 1987, I was going through the Hillman Library card catalogue at the University of Pittsburgh when a friend stopped by. She told me something I would never forget. She said that an eighteen-year-old Indian woman, named Roop Kanwar, had immolated herself on the pyre of her dead husband. I was dumbfounded. Suttee in the twentieth century? It couldn’t be. But The New York Times confirmed the news. The ritual, known as suttee, was witnessed by the townspeople and thousands more came to see it from nearby villages and towns. When the news was leaked the following day, the town was swarmed for days by Indian and international journalists. I was stunned and speechless, my legs laden with lead. At that frozen moment, the seed for this book was planted.

The kernel stayed dormant, but the incident continued to sear like a wound at the back of my mind. The distress was raw, but I was not yet emotionally ready to write about what had happened and how it had affected me. In the ensuing years, I trawled libraries, bookstores, and the Internet, learning about the history of suttee and the cultural and religious traditions in which it is rooted. I studied records of the shrines dedicated to women who had committed suttee. I read the history and mythology of the namesake goddess, spelled Sati. Critically and carefully I analyzed the photographs of Sati temples and studied the engravings, drawings, and paintings of the goddess Sati and the suttee ritual that had been made by British, European, and Indian artists and travelers.

Suttee is a centuries-old Hindu ritual. This ancient belief still persists in some remote corners in India. The belief is if a widow cremates herself with her dead husband, the couple will live in heaven as they did on earth. Furthermore, such a sacrifice guarantees a place in heaven for seven generations for both sides of the family.

The ritual is rooted in the myths of two goddesses: Sati, Shiva’s wife, and Sita, Rama’s wife. Here are summaries of the myths:

Goddess Sati is the daughter of the high priest Daksha. Shiva, the world renouncer, is so awed by her yogic skills and asceticism that he grants her a boon. Sati asks to marry him. He agrees.

Daksha dislikes Shiva. He finds Shiva unconventional and unkempt. Despite her father’s opposition Sati marries Shiva and they live in his mountain abode in Himalayas.

Daksha plans a great sacrifice. He invites all the important divine beings, except Shiva. Sati feels disgraced by the way in which her father has treated her husband. On the day of the great sacrifice, she throws herself in the fire pit meant for the sacrifice. And burns herself to death. When Shiva discovers what has happened to his wife, he is outraged. He pulls out Sati’s half-burnt body, holds it on his shoulders, and in anguish and lamentations whirls around the world.

Goddess Sita is an ideal Hindu wife. Her husband, Rama, is the center of her life. His welfare, reputation, and wishes are most important to her. One day, the demon king Ravana abducts her and takes her to his golden palace. He lies to her that he has killed Rama. Sita is horrified. She moans and tells him that it must have been her fault that her husband was killed. She warns Ravana she could burn him to ashes with the fire of her chastity, but she won’t because she did not have her husband’s permission.

In the end, Rama defeats Ravana and brings Sita home. There he severely tests her loyalty because she has spent days under the control of another man. Sita is shocked at such an accusation. She protests her innocence. She says she has remained wholly devoted and completely faithful to him. Rama persists.

Grieved by his false accusation, Sita asks for a funeral pyre to prove her innocence. A pyre is built, and Sita stands atop it with hands folded. Agni, the god of fire, refuses to harm her because she is innocent and pure. She returns to Rama unscathed. Yet he banishes her to a forest.

Sati and Sita are faithful and chaste wives, and they are devoted to their husbands. The lives of these goddesses are defined by their husbands. Although their dedication and chastity are exemplary, they pay a heavy price for being wives. In both myths, fire plays an important role. Whereas Sati voluntarily kills herself, Sita is saved by Agni. Their god/husbands are alive when the women jump into the sacrificial pit or on the funeral pyre. But ordinary women’s lives are no myths. When a woman is forced into being a suttee, neither her husband nor the god of fire will save her.

The suttee ritual was outlawed by British Raj in 1829. The ritual was described as “heinous rite” when cases surfaced about widows being tied to their husband’s pyre even after being intoxicated with bhang or opium. Many reports of widows escaping and being rescued by strangers were also recorded. Still, more than a century later, scattered instances of the custom have been reported, such as Savitri Soni’s in 1973 and Charan Shah’s in 1999.

The most notorious and controversial case, however, was of Roop Kanwar. Indian people either publicly defended Roop’s action or declared that she had been murdered. Following the outcry that followed Roop Kanwar’s suttee, the government of India enacted the Rajasthan Sati Prevention Ordinance on October 1, 1987. The law makes it not only illegal to commit suttee but also illegal to glorify the ritual or coerce a woman to commit suttee. Glorification includes erecting a shrine to honor the dead woman or converting the place where immolation took place into a pilgrimage site. Derivation of any income from such activities is also banned. The law makes no distinction between a passive observer and an active promoter. Everyone is held equally guilty.

The seed for writing a book inspired by Roop Kanwar’s suttee finally sprouted in November 2009, when I wrote its first draft as part of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), a nonprofit internet organization that supports writers in an effort to complete the initial draft of a novel in one month.

It would take me seven more years to finalize the draft.

The story continued to incubate. I developed the characters, sketched the settings, wrote the narrative and dialogue. But to birth a healthy novel and bring it to life, I had to experience the environment in which Roop Kanwar was born, lived, and died. I needed to converse with the people who allowed it to happen. I wanted to know the antagonist and protagonist’s viewpoints.

I visited India for a month in 2013 for that purpose. I went to the small towns of Deorala, where Roop Kanwar committed suttee, and Jhunjhunu, home of an imposing marble temple dedicated to faithful women who sacrifice their young lives immediately after their husbands’ deaths. The visit stirred feelings of remorse and wonder. Why did people celebrate sacrificial death? How does blind faith hide behind the stunning structure? Domestic and temple architecture, middle and high schools, ancient mansions with bedroom walls made of mirror-mosaics (some now converted to five-star hotels) were breathtakingly beautiful. The local flora and fauna were intriguing, and men and women’s attire colorful. I fell in love with the place. But I wasn’t there as a tourist. I was there to fulfill a quest, to do something about an event that jolted the core of my being.

Meeting with the people of Deorala opened my mind to the fact that a community’s worldview can be so different from my own. Yet my sorrow and awe about Roop Kanwar and my feelings about other widows like her were not alleviated by talking to Roop’s father-in-law, her brother-in-law and his wife, or their neighbors. Nor did I blame them after visiting her neglected and unkempt suttee site. However, the visit helped me better understand the point of view of the town residents. A magnificent temple dedicated to the goddess Sati, which locals honor and regard highly, further clarified their worldview.

My interview with Roop Kanwar’s father-in-law took place in the verandah outside the room where Roop lived with her husband. This was the room where she dressed herself in bridal attire and decked herself in jewelry before following her husband’s dead body to the cremation site. The room has been turned into a shrine, and Roop has become an ishtadevi, a manifestation of Narayani Satimata, a local goddess higher in the pantheon of the thousands of village goddesses of India.

When I asked to go to where Roop performed suttee, her father-in-law declined to walk along, but he did ask other men to take me there. I treaded the path that evidently Roop Kanwar, most probably intoxicated with bhang, walked with the help of two women. They followed her husband’s litter, which four male relatives carried. I was told a lamenting crowd of men, women, and children followed the dead body and Roop as they headed toward her husband’s funeral pyre.

Facing the desolate ground where the ritual had taken place twenty-six years earlier, I shed tears of pain for an eighteen-year-old who didn’t know better, and who no one came to rescue.

The characters in this novel are fictional, but the setting is historic. Writing it does not feel like redemption, for I still ache for the women of the world who are engulfed in outmoded traditions, who are uneducated and dependent. Women with so much potential to offer their families, their communities, and, most importantly, to themselves.

Undoubtedly, the world over, women have made tremendous progress. Yet, the path to elevating women’s social status has many roadblocks, and the process is slow. I sincerely hope The Last Suttee not only helps remove a block or two but also adds substance to the process of change.

Madhu Bazaz Wangu

Wexford, Pennsylvania, USA

August 2017

CHAPTER ONE

The Little Orphan

A policeman holding a little girl’s hand walked inside a building marked SAVE GIRLS SOULS ORPHANAGE. He walked to the front desk. The receptionist, Christina, greeted him with a smile and said, “May I help you?”

“Would you admit this girl?” he said.

Christina hesitated a few moments, then said, “I’m sorry sir. You’ll have to take her to Aasra or Sneh Sadan. At present, we don’t have a room to accommodate her.”

The policeman, who was looking at the girl, jerked his head towards the receptionist and said louder than was necessary, “No vacancy! Is this a hotel? What sort of orphanage are you running if you can’t admit one little orphan?”

“A very well-run place, sir!” Christina said, pointing at the award plaques hanging on the wall behind her. “We take good care of our residents; unfortunately, that’s the reason I cannot admit her. Rooms are crowded. Currently we have four to a room. Not a single space is available.”

“Where is the director?” The policeman looked through the window of the room marked Director’s Office. “What is her name?”

“Ms. Kumud Kuthiyala,” Christina said calmly. “She should be here soon. Please take a seat in the reception room.”

“Do you know what sort of vultures lurk in the city for a girl in her situation? You’d have to admit her… just for a few days…. until I…”

“My heart goes out to her, but the director can’t do anything about it either. I assure you.” Christina had strict instructions not to admit someone unless they could provide a bed and some privacy. “Would you like a cup of tea, sir?” she asked.

He shook his head. “No. I’ll wait.” Reluctantly he sat on a wooden bench against the front wall, his back straight and his legs stretched out. The girl stood next to him with her head bent. He pointed to the seat next to him, but she didn’t move. He gently pulled her to the seat and made her sit. She sat at the edge of the bench, her hands cushioning her bottom.

At that moment, Kumud Kuthiyala entered wearing a crisp cotton peach-colored sari. She was about to turn the knob to her office door when she noticed the policeman and a little girl sitting on the bench. She walked towards them.

“I am Kumud Kuthiyala, the director here. Can I help you, officer?” She said.

She looked like someone in authority who would not mind changing the protocol. “Yes, Madam, you certainly can. This girl was brought to the police station early this morning. The inspector told me to bring her here. But your receptionist tells me you have a policy of not admitting more than a certain number of girls.”

“Yes, that is correct,” Kumud said.

The girl’s face triggered an image from Kumud’s past. In her ex-husband’s neighborhood, a woman had died giving birth, as had the newborn. Her widowed husband had handed over his little daughter, Parvati, to Kumud for safe keeping until he could make some arrangement for her. Taking care of Parvati for a week had been a bright spot in an otherwise depressing and lonely year for Kumud. The memory stirred a tender feeling in her, and she smoothed the girl’s hair.

“I don’t know where else to take her,” the policeman said, his broad shoulders slumping.

Kumud crouched, facing the girl and holding her hand. The director tucked unruly curly bangs behind her small ear and asked, “What is your name, child?”

Kumud looked into the girl’s eyes; they were beautiful, penetrating.

“Alka,” she said softly.

“A perfect name for a girl with black curls!”

The girl nodded. “That’s what my mother says,” she said.

“You look hungry,” Kumud said, standing. “Let’s get something to eat.” She asked the policeman to follow her to the office and instructed Christina to ask Radha, one of the caretakers, to bring two breakfast plates.

“No thanks. I have had my breakfast.” the policeman said to Christina as they entered the office. He pulled out a chair and helped Alka sit on it and then sat next to her. Kumud unfolded a file, took out a form and asked, “Where did you find her, Mister. . .?”

“Tipnis. A construction worker brought her to the police station.”

“A construction worker? And where did he find her?”

“In Kalaba. In a decrepit building that was set to be dismantled years ago. But you know how government works, slower than a snail. Homeless people began sleeping there. Yesterday, when it was finally time to demolish the building, the workers found her sleeping behind a door. She told them her mother had gone to get food.”

Just then Radha, a woman in her late seventies entered with a breakfast plate. Her hands trembled as she placed the tray in front of Alka. Yuna Li, the previous director, had hired Radha when the founder of Save Girls Souls Orphanage (SGSO), Nari Millwalla, was alive. In the ensuing twenty years, Radha, once energetic and efficient, had become slow and enfeebled. The passing years had snatched her strength and agility. Kumud knew she needed to hire a younger woman but didn’t have the heart to let Radha go.

Radha asked if they needed anything else.

“Would you like a cup of tea or coffee, Mr. Tipnis?” Kumud asked.

He politely declined. Kumud shook her head and Radha left.

Alka gulped down the milk and ate a piece of toast.

“She must be famished. I don’t think she’s eaten for a day or so. I offered her biscuits when they brought her to the station, but she refused,” he said.

“Wonder why her mother did not return?” Kumud said, more to herself than to the police officer.

Moving closer to Kumud, the police officer whispered, “We found the body of a beggar woman, a hit and run, on the side of the road, about a mile from the building. Perhaps that is why.”

“Oh, Ma!” Kumud cried out and pressed her palms to her eyes. When she opened them, Alka was munching on a second slice of toast. After finishing the bread, Alka picked up the glass, tipped it between her lips and emptied the glass of milk.

“More milk?” Kumud asked, and the girl nodded yes. On the internal phone line, Kumud rang Christina for another glass of milk. Tapping her fingers on the desk trying to think of some way to admit Alka. She turned to the officer and said, “As our receptionist informed you, Mr. Tipnis, we don’t have a single bed available. I feel bad.”

“Why can’t you let her sleep on the floor? It is better here than Aasra or Sneh Sadan. Those orphanages are terrible,” he said, his forehead furrowing.

“Thank you, but we must follow our founder’s policy. We aren’t permitted to change or modify it,” she said hesitantly.

“I guess I could drive her to the orphanage at the other end of the city, but that one is also a madhouse!”

Radha entered the room quietly and handed a second glass of milk to Alka, then cleared the tray from the table.

Christina peeked in the office and said, “Madam, the caterer is here!”

“Oh, I almost forgot!” Kumud said, looking at her wristwatch, then at Alka. “Finish your milk. The policeman will take you to another place for now. I’ll try my best to bring you back here. Okay, Alka?”

Looking a bit confused, Alka got up and held policeman’s hand. The bangs behind her ear came loose, and the memory of Parvati again stirred in Kumud’s heart.

“I’m so glad we met,” she said to Alka. “Let me walk you to the door. I’m sorry, officer!”

“Thanks anyway, madam.”

At the door, Kumud watched as the policeman and Alka walked away. Her gaze followed them as they entered the parked Jeep.

When Kumud turned back towards her office, she saw Veena’s wedding caterer waiting on the bench. Veena was Kumud’s first ward at SGSO. She was getting married to her sweetheart, Vinod. The wedding would be the orphanage’s first big event under her directorship.

“Why so sad, Kumud Madam?” the caterer remarked. “Veena Bitiya has not left yet. A few more weeks before she goes.”

Suddenly, Kumud remembered that Veena was getting married, interviewing for jobs and would be leaving the orphanage soon.

“Please wait, I’ll be right back!” She said to the caterer and ran out of the room.

A few minutes later she returned holding Alka’s hand.

“You are a fortunate little girl,” the caterer said to Alka. “Out of hundreds of girls like you in this metropolis, you are lucky to have been brought here at the moment when another girl is about to leave.”

This excerpt of The Last Suttee by Madhu Bazaz Wangu is published here courtesy of the author. It should not be reprinted without permission.