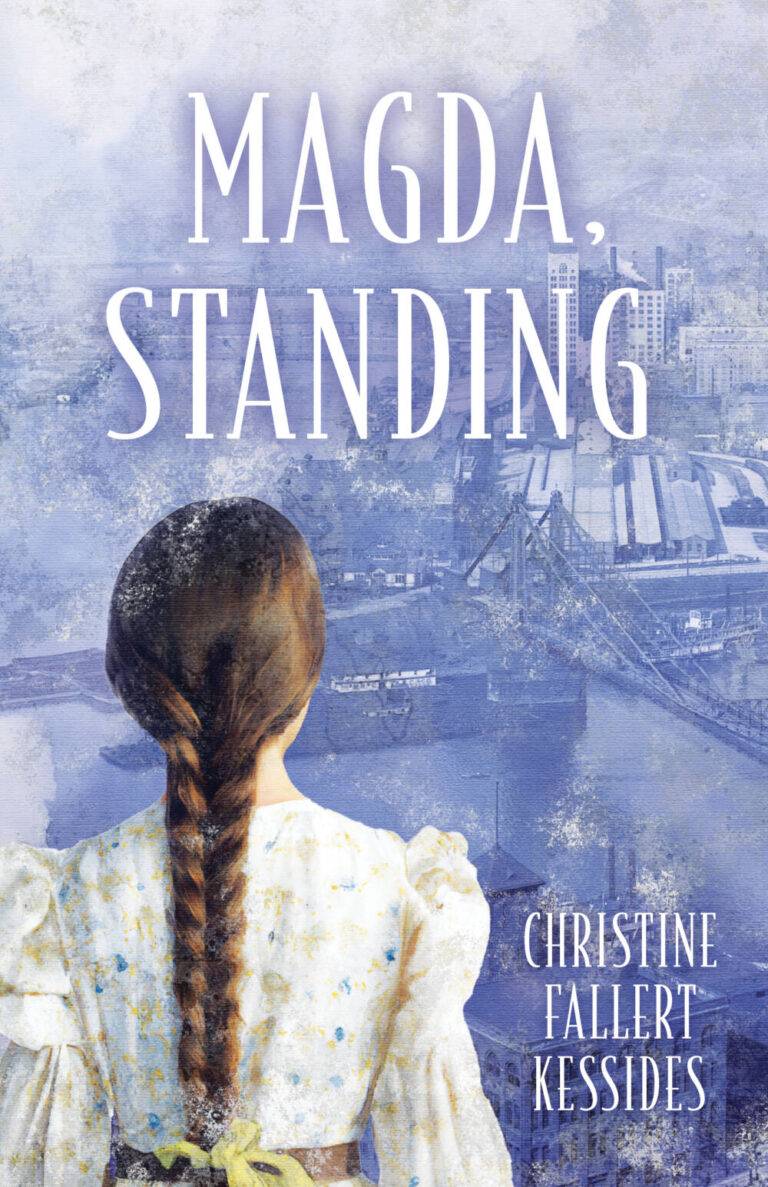

From the Publisher: “When her father pulls her out of high school to care for her invalid mother and little brother, sixteen-year-old Magda is devastated—but the greater challenge is saving her family in the midst of a global war and pandemic.

In 1916, the world is at war, even if America has not yet joined the effort. But for Magda, the growing hostility surrounding her German immigrant family in Pittsburgh hits close to home. Despite her domestic obligations, Magda persists with her education, determined to find an independent role for herself. Faced with the mounting crises of the Great War and the Spanish flu, Magda seeks the knowledge and strength to protect those she loves most.

Standing up to a war and pandemic, traditions and expectations, Magda embarks on a journey of self-discovery and resilience that leads her back to embracing her family and caring for a wider community…”

More info About the Author: Christine Fallert Kessides was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and was always interested that all her ancestors (those she could identify) were from Germany. After reviewing her family genealogy and reflecting on some of her relatives’ experiences, she was inspired to write Magda’s story.

Christine attended college and graduate school at Northwestern University and Princeton University, respectively. She had a career writing policy reports for the World Bank in international development. In her spare time she volunteers with nonprofits that support women and families and especially enjoys reading, travel, yoga and sharing books with friends. She lives outside Washington DC, in suburban Maryland with her husband, and sees their four children, grandchild, and granddogs as often as possible. Magda, Standing is her first novel.

For more information on the book, related historical references, and discussion questions see: www.magda-standing.com

Author Site

- Winner of Maryland Writers Association Award for Young Adult Novel

- Gold medalist – 2024 Ben Franklin Award from Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA) – for Young Adult Audiobook

- Silver medalist – 2023 Story Circle Sarton’s Book Award -Young Adult category

- Silver medalist – 2024 Florida Authors and Publishers Association (FAPA) Award for Young Adult Fiction

- Bronze medalist – 2023 MOONBEAM Children’s Book Award – Young Adult Fiction: Historical/Cultural

- Finalist for 2024 Independent Author Network Book of the Year – Fiction Teen/Young Adult

- Finalist for 2023 international Eyelands Book Award for published Historical Fiction/Memoir

Author Q&A

Magda rode the trolley toward home as usual with Lucia, who chatted about her plans to spend several weeks with cousins near Conneaut Lake, just north of Pittsburgh. Magda’s family never took a vacation, but she looked forward to spending as much of the summer outdoors, with friends and a good book, as her regular chores allowed. Magda squeezed Lucia’s hand as they parted near their houses; she always tried to go into hers alone. Her heart beat fast, despite the slow pace of her steps.

Papa had completed his milk deliveries, and he and mama sat in the kitchen when Magda entered. Crumbs of bread and cheese speckled the table. Dirty dishes from breakfast lay encrusted in the sink. Magda handed her report card to papa first with a small flourish. “The principal announced I’m in the honors society!”

Without a word her father put on his glasses and read the card, rubbing his beard. He showed it to mama, who gave it a quick glance and a wan smile. Magda’s heart pounded louder when she saw his frown as he handed it back.

“Magdalena, you are a good girl and you make us proud. Hard-working and smart, like all of our family. But—”

Magda’s fear burst out of her throat. “No, Papa, you won’t say—?” Her fingernails cut into the card.

“I already said that you do not need to finish the high school. You can learn the rest of what you need to know by reading, as we all did, while you help your mother here.”

Magda stared at her father with wild eyes. “No, I can’t! I want to learn more.”

“Hear me out, my girl.” But why couldn’t he listen to her? “You’ve already got more schooling than the rest of us.”

It was true that Magda’s parents only finished six years of primary, back in Germany. Instead of attending high school, her brothers Tony and Fred had gone to learn trades and her sisters, Kitty and Willa, took paying jobs with their domestic skills outside the home. While Magda didn’t envy the working lives of her siblings, it seemed they’d at least found paths that satisfied them. Her choice—her need—was to continue school.

“Papa, you always wished you could have gotten more education!”

“And yet, I didn’t. My family needed me. Your mother needs you to take care of the baby and the house. More useful experience for when you have your own family.” Papa looked away when he said this, as if he didn’t want to see the heartbreak in Magda’s eyes.

Magda turned, pleading, to her mother, who was gazing down at little Richy on her lap. Her hair was uncombed and she still wore a soiled house robe. She didn’t return Magda’s frantic stare. Mama had been especially quiet and sickly since the child was born two years ago. Most of the time, Mama seemed detached from her own life, as if it was something happening to her, beyond any of her control. Exactly what Magda would refuse to accept herself.

Magda had been the youngest for almost fourteen years and had gotten used to a bit of freedom. With older sisters she had been able to escape many household duties. By studying diligently, Magda had hoped she could plan a life much different from that of most women and girls in the community. Certainly, different from her mother’s.

Magda clenched her fists and leaned towards her father. “Doesn’t it matter what I want?” Her voice rose and her face flushed in resentment. He didn’t answer.

Her hands shook as she struggled to continue, knowing she had already violated one of the basic rules of the family—no talking back to adults. But her head was on fire and she couldn’t stop. “I always brought home the best grades. And now you say I have to leave school for good? To stay home? How is that fair? Even the principal said he expects me to continue my studies and,” she put the words into his mouth, “not waste my good mind!” It landed like a slap.

Papa rose from his chair, his hand rubbing his bad hip. “Calm down, Magda.” His voice was hard and he shook his head with the anger that Magda knew he was holding back in front of mama. “Your brothers and sisters quit school to work because we needed the money when I lost my job at the mill. I could hire the woman to look after us for a while, but we can’t afford to keep her any longer—we have many more expenses. We must take care of our own. Your mother isn’t well.”

So that was it? Magda was the unlucky one, to be shut in at sixteen and made to feel guilty too, for objecting. Hot tears welled, but she refused to cry here. Mama looked sad and dazed—whatever her thoughts about this decision, she would not say in front of them both. Everyone in the family was used to papa having the last word.

Taking a deep, shaky breath, Magda reached for the toddler and took him from mama, who didn’t resist. “I’ll put him down for his nap, then go to the baker.” Her head ached from holding back the sobs that rose in her throat. She had to get away and think about what to do. The house was silent as she left, letting the door slam behind her.

+ + +

The next day felt like the beginning of the end of Magda’s life. She scraped papa’s shirt collar against the washboard. Two minutes each, mama always said—the time it takes to say one Our Father and Hail Mary. The corrugated metal surface bruised her knuckles and the raw skin started to burn. She rubbed the rough soap bar against the collar again, but the dark stains refused to disappear. Papa’s sweat mixed with the dirty air of the city made his shirt collars the worst part of the weekly laundry.

No, the baby’s diapers were a messier job, and the sheets and towels took too much strength for Magda to wash by hand. Mama had said she’d let her avoid all that by convincing papa to use a neighborhood laundress with one of the new electric washing machines. That promise was mama’s small gesture of compensation for his announcement the previous day. Papa had objected to the expense and only agreed because mama said they would save water and soap, and that it would be temporary, for maybe another year or two. Mama rarely took such initiative and didn’t seem to have challenged Papa’s decision about school, but when she did express a quiet wish papa often gave in—hoping, perhaps, to spark an uplift of her moods.

Thinking of papa’s words made Magda’s stomach burn. Really, reading as an alternative to the classroom? That worked for him—papa read two newspapers a day, American and German, and she knew he could hold his own debating politics with better-educated neighbors. She did love reading, but to feed her imagination; to see what was possible in the world and, perhaps, in her own future. Most importantly, she wanted options other than getting married and caring for a household—to be more independent and make a bigger contribution with her life. Maybe healing sick people, and discovering a cure for whatever ailed mama.

Magda was upset that she had not prepared a better argument. Papa always called America the land of opportunity—but evidently not for her. She didn’t want to compare herself to most young people in the community, whose families may also have considered public high school an unnecessary detour from responsibility. But what could she have said? That she wanted a better life than that of her parents, maybe even better than the rest of the family? And that for all her efforts, she deserved more? But that would sound too selfish; besides, his mind was already made up.

Now she would be humiliated in front of her friends. How could she ever face them again?

Magda finished hanging papa’s shirts on the line behind the house to catch the afternoon breeze. She decided on her first step: she would talk to her aunts.

She checked that Richy was napping in his crib beside their parents’ bed. Mama was resting and didn’t rise when Magda whispered that she was going to run an errand and would be back before long. She left the room before her mother could reply.

Stopping by the small bathroom, Magda splashed some water on her face, which was red and damp from the exertion. Disheveled braids barely held her thick brown hair, but she didn’t want to take time to redo them. From the bedroom shared with her sisters she grabbed her hat, which the aunts would insist was proper wear for a young lady outside the home. She slipped the money for the butcher papa had given her earlier that morning into her pocket, headed downstairs and out the back door. She closed it gently, praying Richy’s sleep wouldn’t be disturbed.

The thick gray haze was typical of almost any day in Pittsburgh. A bit of blue might appear for a little while, but the smoke and ash from the iron and steel mills formed heavy low clouds that combined with the mist lifting off the rivers. Soot would settle on windows, on doorsills, on white fences and white dogs, and on clothes hanging out to dry. Often it was necessary to shake down the sheets, towels, and everything else before bringing them inside to be ironed. Worse were the particles of grit she sometimes felt herself almost chewing and swallowing. She would spit them out, or sneeze dark specks into her handkerchief. And many people, especially men who worked in the mines outside Pittsburgh and in the mills, breathed it till they coughed a blackish froth. Papa used to do that for years after he left that job.

Magda didn’t feel sympathy for him now, only for herself. She strode along the steep brick sidewalks of Mt. Oliver, its streets lined with close-set houses and small shops, many seeming to be cut from, or clinging to, a hillside. Her heels fell hard against the uneven ground and she swung her arms as if to warn passersby to step aside.

She arrived at her aunts’ house with sweat running down her face, out of breath. Magda took several moments to compose herself, straighten her hat, and smooth her skirt in the shade of a tree. It took an effort to be decorous. She wanted to make the best impression, and the city’s humidity was only partly to blame for her wilted appearance.

The aunts were well-known in the neighborhood. Theirs was the only influence in the family that matched that of papa. Aunt Philomena, or Minnie to those close to her, was her mother’s elder sister by six years. Aunt Matilda, whom everyone called Tilly, was two years younger than Minnie. They had come to America on the same crossing as papa, but hailed from a different part of Germany. They supported themselves initially by tutoring other German families’ children and, after taking certification courses at night, worked their way to teaching in public schools in the city. Magda noticed that everyone—the neighbors, the postman and policeman, and even the Monsignor—treated both aunts with great regard. Neither aunt had married. The aunts had always been a nurturing presence in Magda’s life, and an inspiration. She was determined to find out what they could do for her now.

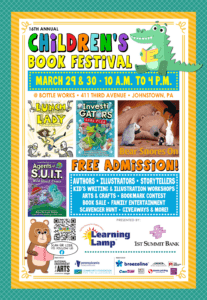

Q&A: Christine Fallert Kessides (Author of Magda, Standing – Set in Pittsburgh!)

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.