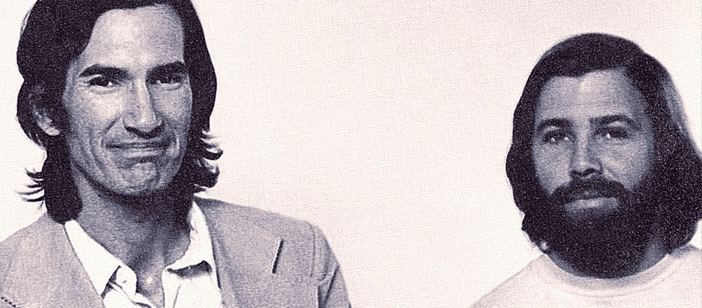

From the publisher: “‘Other people locked themselves away and hid from their demons. Townes flung open his door and said, “Come on in.”‘ So writes Harold Eggers, Townes Van Zandt’s longtime road manager and producer, in My Years with Townes Van Zandt: Music, Genius, and Rage – a gripping memoir revealing the inner core of an enigmatic troubadour, whose deeply poetic music was a source of inspiration and healing for millions but was for himself a torment struggling for dominance among myriad personal demons.

Townes Van Zandt often stated that his main musical mission was to ‘write the perfect song that would save someone’s life.’ However, his life was a work in progress he was constantly struggling to shape and comprehend. Eggers says of his close friend and business partner that ‘like the master song craftsman he was, he was never truly satisfied with the final product but always kept giving it one more shot, one extra tweak, one last effort.’

A vivid, firsthand account exploring the source of the singer’s prodigious talent, widespread influence, and relentless path toward self-destruction, My Years with Townes Van Zandt presents the truth of that all-consuming artistic journey told by a close friend watching it unfold….”

About the Authors:

Harold F. Eggers, Jr. of Austin, Texas, is a music industry executive of 40 years’ experience, who worked with Townes Van Zandt as road manager, business partner, and co-record producer, helping bring the songwriter’s unforgettable music to live audiences across Europe and North America over a span of two decades.

L. E. McCullough has worked as a journalist, musician, arts administrator, and script and stage writer with 52 books published in fiction, nonfiction, and drama. He is the author of hundreds of articles on music and the music industry. Dr. McCullough holds a PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Pittsburgh and lives in Mount Washington with his wife, actress Lisa Bansavage.

Prologue, 1978: “Everybody here’s crazy except me!”

THE RINGING PHONE echoed through my small apartment on Belmont Boulevard in Nashville, interrupting my first cup of coffee on a chilly morning in early December. Picking up, I heard a woman’s voice screaming and sobbing.

THE RINGING PHONE echoed through my small apartment on Belmont Boulevard in Nashville, interrupting my first cup of coffee on a chilly morning in early December. Picking up, I heard a woman’s voice screaming and sobbing.

“Harold, it’s an emergency! You need to get out here right away! He’s flipped out!”

She paused, her breath coming in ragged gasps. “Harold, please hurry, it’s really serious this time.”

The screams, sobs and gasps belonged to Cindy, the eighteen-year-old second wife of Townes Van Zandt, the critically acclaimed singer/songwriter with whom I had been destined to work as road manager by a perverse, prankish, music-loving committee of Fates.

“I’ll be right there. Just keep him calm.”

“He’s chained to a damn tree. It’s as calm as I can get him for now.”

I sighed and hung up, grabbing my coat and keys and rushing to the car for the picturesque ride to the Van Zandt homestead in rural Franklin, about thirty miles distant. No doubt about it: the next few hours were going to deduct a year or two from my lifespan.

I drove past Music Row and turned onto 21st Avenue, threading my way quickly through lingering rush hour traffic and keeping a sharp eye out for cops, a skill I had honed during my time touring with Townes.

I followed 21st Avenue out of Nashville as it turned into Hillsboro Road and moved deeper into the rolling countryside. Born and bred in suburban Long Island, I couldn’t help but feel a mixed sensation of uneasiness and liberation whenever I ventured into a non-urban area … especially the 3,000 acres of isolated backwoods where Townes had fabricated a survivalist retreat and occasional drinking club for Nashville’s renegade singer/songwriters.

Chained to a damn tree. I couldn’t resist a chuckle at the thought of Cindy, frizzy mane of bright red hair streaming over her thin shoulders, wrestling the big logging chain around Townes. Soft-spoken with delicate, elfin features, Cindy was, nevertheless, the daughter of a long-distance trucker and possessed of fierce determination with regard to Her Man. Within a few months of living with Townes, she had become adept at the art of physical restraints.

I turned off the main highway onto a two-lane blacktop, wheeling past a medium-sized critter carcass mashed into the asphalt. Following the road’s winding course through the hills along the Harpeth River, I reflected on having made it through my first full year as Townes’s road manager.

And wondered if I’d make it through another.

To a great degree, the partnership of solo performer and road manager resembles a short-term shotgun marriage born of economic necessity and scheduling convenience. It is an intimate relationship that crosses all personal boundaries as the partners work, travel, eat, sleep, converse, and carouse in the closest proximity every hour of the day for months at a time.

An efficient road manager must be prepared for every conceivable situation and challenge that could possibly arise during the course of the tour.

In my case, the chief challenge was to get Townes from one gig to the next without either of us dying in the process.

I had gotten the job through my older brother Kevin Eggers, founder and president of Tomato Records. In 1976, Tomato had re-issued Van Zandt’s first six albums recorded from 1968–72 by Poppy Records (Kevin’s earlier label), including 1972’s The Late Great Townes Van Zandt that had received enough distribution and radio airplay to make national tours feasible and—were it not for the excesses of Townes’s touring regimen—potentially lucrative.

Unlike his more notorious musical peers, Townes Van Zandt’s pop-star idiosyncrasies did not involve group sex, expensive limos, or trashed hotel rooms. Instead, his preferred method of unwinding after a gig was to have us drive to the local Skid Row where we would seek out winos sleeping on the sidewalk or huddling around trash fires.

Townes would distribute ten- and twenty-dollar bills, joking, “If I’m ever here again, at least I’ll be able to score a drink.”

While I was moved by Townes’s genuine compassion toward the poor, homeless, and mentally ill, I was less enthusiastic about the surprise occasions when Townes would invite a particularly down-and-out street person to spend the night in our hotel room.

I learned to sleep with my hands in my pockets, holding on to our travel money and praying I’d awake alive and in one, un-strangled, un-stabbed piece.

Even more disconcerting was Townes’s propensity to seal newly-made friendships by taking out a pocket-blade, digging a deep chunk of skin from his wrist and offering to be “blood brothers”.

This ritual, I discovered, could occur within the same hour as Townes becoming enraged at a perceived slight and confronting the offender with the chilling statement, “I’ll slit your throat and drink your blood.”

It was a dark, unpredictable side I had not anticipated. Townes had been a frequent visitor to our family home during the late 1960s when I was a teen. Townes had even served as a co-godfather for my brother Kevin’s daughter, Mary, in 1972.

For me, getting the call at age twenty-seven to be road manager for my brother’s top label act was a personal honor and profound responsibility. It was like acquiring a hipper, more exotic godfather of my own generation while having the chance to be involved with my brother Kevin, whose success as a rising music executive I hoped to emulate.

Naturally, I jumped at the chance and laughingly remarked to friends that traveling the U.S. with Townes couldn’t be any more dangerous than my in-country tour of duty in Vietnam. Boy, was I wrong about that . . .

The whiff of fresh cow dung snapped me back into present tense mode. I brought the car to a stop at a cattle guard after passing through the sedate confines of an exclusive new housing district recently carved from the rump acreage of an old tobacco farm. Beyond the guard, the road sank into a rutted dirt path, barely wide enough for one vehicle. A mile across the fields and through a creek, past a long-abandoned farm house, the path ended at Townes’s “cabin”– a decrepit shanty inhabited in past decades by sharecroppers.

I sat at the wheel for several moments, engine idling, envisioning the scene that lay ahead. Maybe I should turn back and get the hell out of here. Work for some rational person, at least somebody half-less nuts. It’s not like this folkie stuff is going to make anybody rich . . .

I gunned the motor and forged ahead. What the hell . . . a brother was a brother, blood or otherwise.

I topped a rise and saw three vehicles parked thirty or so yards up ahead. Cindy was crouched behind one of them — a Chevy four-door sedan that belonged to John Lomax III, who had started in as Townes’s business manager the last year or so. And who was now crouching behind his car alongside Cindy.

John was the grandson of John Avery Lomax and nephew of Alan Lomax, renowned Texas folklorists and collectors of American folk song who had reshaped and revitalized American popular music by bringing songsters like Leadbelly, Willie McTell, Woody Guthrie, and countless other blues and country performers to widespread public notice during the 1930s and ’40s. Cindy had called John after rousing me, hoping that strength in numbers would prove a settling influence on her husband’s mania.

I parked my car and got out. I looked past Cindy and John and spied two figures lying at the base of the oak tree — Townes and the family dog, Geraldine.

Townes’s eyes were closed, and he held a shotgun in his right hand and a half-gallon jug of vodka in his left. Geraldine, a bright-eyed, two-year-old German Shepherd-Husky mix, sat by his side, panting patiently and glancing intently at the crescendoing medley of morning critter noises peeping from the surrounding forest.

I could hear Townes muttering. “The Plan . . . ever’body jhhoin The Plan . . .”

I went over to Cindy and John. “He’s driving me crazy,” Cindy whined. “Look inside the cabin, he tore up the whole damn place.”

According to Cindy, the human half of the oak tree duo had been drinking steadily for three days without any sleep. This was not in itself unusual when Townes was at home off the road, but that morning, she reported, Townes had wordlessly chopped off his shoulder-length hair with a chipped butcher knife and daubed his face with red, green, and yellow finger paints in an effort to achieve the classic Plains Indian battle design.

After shouting for a half hour at a stereo speaker he thought resembled a promoter who had once cheated him, he’d pulled out his .357 Magnum and shot a few holes in the rear cabin wall, thinking he might get lucky and nail one of the Black Ghosts he believed inhabited the back part of the residence. Pausing to reload, he had told Cindy to chain him to the tree so he could meditate and work on The Plan.

Were it not for the modern trappings of overhead phone wires and automobiles in the driveway, the moaning, paint-streaked man with a chain cinched around his waist could have been mistaken for a 19th-century Sioux warrior in the last throes of a mighty vision quest.

The Sioux had used fasting and prayer to seek a personal guiding spirit that would strengthen the warrior through his life journey. The quest sometimes involved significant suffering and deprivation, but lasted no more than four days.

Townes Van Zandt’s vision quest was into its second decade with no discernible evidence of guiding spirits other than alcohol and rage. Some people might have been freaked out. I’d come to view it as artistic evolution.

This was, after all, the same Townes Van Zandt who just three years earlier had charmed his way through the movie Heartworn Highways, a groundbreaking documentary on the bold new wave of Nashville singer/songwriters in which Townes accounted for two of the film’s most captivating moments, eliciting both laughter and tears.

With a bottle of whiskey in the crook of his left elbow and a shotgun in his right hand he had introduced himself, Geraldine, and Cindy to the camera, proceeding to regale the gullible film crew with a wild story about raising giant rabbits in his back yard. Suddenly, Townes slid feet first into a hole, completely disappearing into the ground, yelling that the giant rabbits were pulling him down.

A few scenes later, Townes sang “Waiting ’Round to Die” for Uncle Seymour Washington, an elderly black man and neighbor. Tears rolled openly down Uncle Seymour’s face, with the line “Seemed easier than just waiting around to die” evoking a shuddering burst of lamentation from the old man. Seamlessly shifting between hillbilly clown and cathartic healer, the Texas-born troubadour had already established his stage persona as an eccentric but powerful musical shaman who could render a packed room spellbound with a simple guitar chord and the merest whisper.

He had also begun creating a body of lyrical work that would outlast his own tortured life and premature death in just twenty years at age fifty-two. Two of his songs, “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You”, would in five years be huge crossover hits for several top country music stars and ensure his place in the American musical canon as a gifted, innovative songsmith.

But now, as the pale winter sun dappled the valley, the notion of a promising future as a major recording artist seemed as implausible as the surrounding forest suddenly parting to reveal an ocean liner loaded with vacationing Sioux vision questers.

This excerpt from My Years with Townes Van Zandt: Music, Genius, and Rage is published here courtesy of the authors and should not be reproduced without permission.