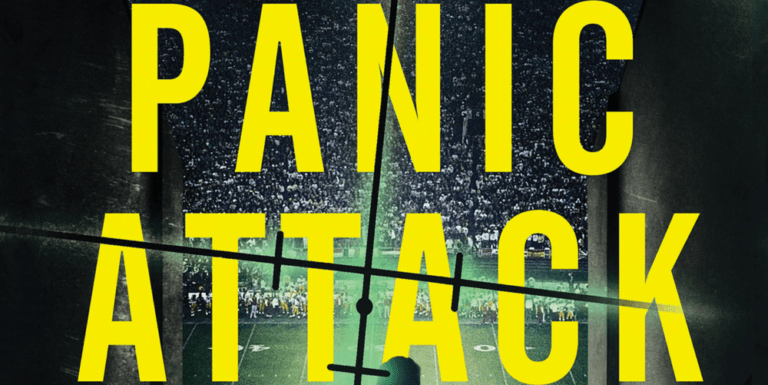

Formerly a Hollywood screenwriter (of My Favorite Year, Welcome Back, Kotter, and more), Dennis Palumbo is a licensed psychotherapist and author. His mystery fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, The Strand and elsewhere, and is collected in From Crime to Crime (Tallfellow Press). His series of mystery thrillers (Mirror Image, Fever Dream, Night Terrors, Phantom Limb, Head Wounds, and the latest — excerpted here — Panic Attack) all feature Daniel Rinaldi, a psychologist and trauma expert who consults with the Pittsburgh Police.

From the Publisher: “Psychologist Daniel Rinaldi is no stranger to trauma. A survivor of not one, but two attempts on his life by a deranged killer, the therapist also counsels trauma patients in his private practice, and contracts with the Pittsburgh Police to help victims of violent crime cope with their experience. When a sports mascot is gunned down mid-field by a sniper at a college football game he attends, Rinaldi becomes an accidental yet integral part of the investigation. To begin with, the victim in the costume is not the person who was supposed to be wearing it…”

Praise for Dennis Palumbo’s Daniel Rinaldi Series:

“Accomplished writer Dennis Palumbo calls his latest novel Head Wounds and the grim title should serve as a warning. This psychological thriller has some fine language and a strong narrative pull that keeps the pages turning, but the series of crimes that occur are unnerving…People in the story wear Pitt Panthers and Steelers sweatshirts, drive on the parkway, and get their news from KDKA. Mr. Palumbo often does more than just mention Pittsburgh landmarks; he characterizes the city in both positive and negative ways…As Head Wounds rolls to its clever, crazy gothic conclusion, no one could accuse Mr. Palumbo of being flat. This is the fifth book in his Daniel Rinaldi series and most readers will hope Dan lives to see a sixth.”

— Pittsburgh Post-Gazette“Head Wounds delivers relentless action toward a climax as vivid and harrowing as anything I’ve ever read.”

— Joseph Finder, New York Times best-selling author of The Switch“The character of psychologist and trauma expert Daniel Rinaldi gives great heart to this story and elevates it to novelistic heights.”

— John Lescroart, New York Times best-selling author of Damage“Lovers of noir will enjoy Dan Rinaldi’s fast-paced adventures. Rinaldi, an empathic therapist, is on call to the Pittsburgh police. He needs every ounce of his Golden Glove skills to survive the violent world of Pennsylvania politics.”

— Sara Paretsky, Mystery Writers of America Grand Master, author, V.I. Warshawski novels“A gripping thriller, chock full of the desired twists and cliffhangers, with the added layer and intriguing access of a therapist narrator/detective. A page turner!”

— Aimee Bender, New York Times best-selling author of An Invisible Sign of My Own

Chapter One

On a bitterly cold afternoon in late October, I was one of twenty thousand witnesses to a murder.

On a bitterly cold afternoon in late October, I was one of twenty thousand witnesses to a murder.

Not ten minutes before, I was sitting next to Martin Hobbs, Dean of Teasdale College, sipping spiked cider from a thermos, my head sunk low in the collar of my winter coat.

Above, enormous white clouds loomed like a chain of floating islands, backlit by a wan sun whose diffused light crowned the trees still boasting autumnal colors. Beyond, a carpet of crisp, freeze-dried grass stretched to meet the ancient Allegheny Mountains. A typical fall landscape in Western Pennsylvania, yet less than twenty miles from downtown Pittsburgh. In a small, formerly thriving farming community called Parkville.

“Isn’t this great, Dr. Rinaldi?” Dean Hobbs rubbed his gloved hands in excitement. “Perfect football weather, eh?”

I nodded, shivering. We were in the cushioned VIP seats, right on the fifty-yard line in the small private college’s new football stadium. I’m more of an NFL fan, especially when it comes to the Steelers, and hadn’t been to a college game since my undergraduate days at Pitt. But when the Dean asked me to join him for Saturday’s match-up against the team’s division rivals, I didn’t see how I could refuse.

The evening before, I’d given the Commencement address in the Reynolds Auditorium, another newly-built facility on the rural campus, a gift of billionaire alum William Reynolds. Having amassed a fortune in real estate, the late philanthropist had earmarked the funds for the stately building in his will.

Now, with kick-off only a few minutes away, I let my attention drift from Dean Hobbs’ relentless boosterism and replayed my speech from the night before. It had gone reasonably well, though both the school’s faculty and its graduating class were perplexed by the phalanx of print, online and broadcast journalists who rushed me as soon as I’d finished.

I couldn’t believe I was still news, now more than eight months after the Sebastian Maddox case. Although I’d done my best to keep a low profile, the media wouldn’t let the story go. Just last month, I was approached by a cable news producer who said they were planning a special about the crimes, and would I agree to be a participant in the program?

Naturally, I refused. Not that they needed my onscreen presence, anyway. There was enough news footage from that period–the various bloody crime scenes, the smoking remains of the fire that had raged through the psychiatric clinic; there’d even been coverage of the last victim’s funeral. After all, the mayor himself–never one to pass up a photo-op–had attended that gaudy affair.

To me, this proposed “special” was nothing but a particularly gratuitous exploitation of a real tragedy. What my late wife used to call “murder porn.” And I was having none of it. Those horrific days left psychic scars on me as fresh as when they’d first been inflicted. Not to mention what had happened to friends, colleagues and patients. Eight months of therapy later and I still barely slept at night.

But the Maddox case, following on the numerous high-profile investigations I’d been involved with in recent years, had cemented my reputation as both a psychologist and consultant to the Pittsburgh Police. A PR guy even called, offering to help me enhance my “brand.” I couldn’t hang up fast enough.

Nowadays, unlike in those earlier cases, and especially in recent months, I made sure to stay out of the public eye. No more interviews with the Post-Gazette, no more “expert” commentary on CNN about the possible motives behind the latest mass shooting or new string of serial killings. Like the victims of violent crime that I specialized in treating, I needed time and therapeutic support to address my own traumatic reaction to what Maddox had put me through. Lately, other than a few intimate meals with close friends and my ongoing clinical practice, I’d kept mostly to myself.

So when the invitation came to speak at Teasdale College, a modest private institution east of the city, my initial reaction was to politely decline. Until I mentioned it to my own therapist, who suggested it might aid in my recovery to, in his words, “return to the land of the living.”

Which is how I ended up cupping a thermos of not-quite-spiked-enough cider and smiling as attentively as I could while Dean Hobbs prattled on about his school. In his late fifties, reed-thin and balding, his neck swathed in a scarf emblazoned with Teasdale’s colors, he’d finally taken a breath and glanced at his watch. Small, inoffensive eyes gleaming merrily.

“Almost time for the tiger.”

“What tiger?”

“The Teasdale Tiger. Our team mascot. The fans love him. Especially the kids.”

He nodded at the home team’s sidelines, where in addition to legendary local coach George Pulaski and his heavily-jacked players, a two-legged tiger was doing deep knee-bends.

It was a full-body costume, complete with a head cover whose dark, whiskered snout and muff collar looked appropriately tiger-ish. There were also impressive-looking claws on the furry hands and feet, and a floppy tail. For a moment, I wondered how the guy inside the costume could breathe. On the other hand, he was probably warmer than anyone else in the stadium.

Dean Hobbs nudged me. “Know who’s in the tiger costume?”

“No.”

A conspiratorial chuckle. “Neither does anyone else. Only Coach Pulaski and I know. It’s an idea we borrowed from Pitt. Their Pitt Panther mascot.”

Of course, I knew what he was talking about. For years, my alma mater, the University of Pittsburgh, kept the identity of its similarly-costumed football mascot, the Pitt Panther, a secret. All anybody knew was that it was one of four undergrads who rotated in the job, all of whom had been sworn to secrecy. Even after they graduated, they kept their promise not to reveal that they’d worn the fabled costume. Only the university’s Provost and the football coach knew their names.

Hobbs took a sip of hot chocolate from his own thermos, embossed with the school’s logo. The guy was a walking advertisement for the campus store.

“Now in our case, Doc,” he said casually, “we only have one student per year who dresses as the Tiger. This year it’s a sophomore bio major named Jason Graham. Great kid. Really likes to put on a show for the crowd.” A worried frown creased his brow. “I assume you’ll keep that information to yourself.”

“I’m a psychologist, Martin. I keep secrets for a living.”

He breathed a sigh of relief as I swept the tiers of seats all around the stadium.

Since many of the fans were returning alumni of Teasdale, I found myself wondering which, if any, had himself once worn the tiger outfit. And who, many years later, having weathered the pains and indignities of life, now looked down at the energetic student doing push-ups on the sidelines and recalled the carefree days of his youth.

Or maybe I was thinking about myself. All the unexpected twists and turns of my own life since my early years at Pitt.

The long, complicated journey that’s led to where I am now.

Suddenly, my reverie was broken by a tremendous uproar from the crowd. No surprise why. The Teasdale Tiger had taken to the field, doing cartwheels on his way to the middle of the artificial turf.

Dean Hobbs had joined the rest of the fans in jumping to his feet, whistling and shouting. I hauled myself out of my seat as well.

I had to admit, it felt good being enveloped by the enthusiastic energy of the crowd. After all these somber, halting months, obsessed with what Sebastian Maddox–in his fury at me–had done to those closest to me. The grief, the guilt. But now something about that lunatic mascot cavorting on the field, leading the fans in a protracted “tiger roar,” gave my spirits a lift.

Until a few seconds later, when, as the crowd noise lessened, it was replaced by another sound. A loud, booming crack, like a tree branch breaking in a storm.

A gunshot. From somewhere above and behind where Hobbs and I stood.

I whipped my head around, eyes sweeping the mass of people behind me, some of whom had themselves frozen in place.

Then another sound, a massive collective groan from the stands, brought my gaze back to mid-field.

It was the mascot. The Teasdale Tiger.

On the ground. Motionless.

People yelling, screaming, crying. Some so stunned they stood rooted at their seats, others scrambling over seat backs and down the slanted aisles toward the field.

Given our VIP seats, Hobbs and I had been among the first to reach the fallen student, though the Dean had just as quickly back-stepped away, hand on his mouth. Meanwhile, the entire team had poured from the sidelines and stood, wide-eyed, stricken, in a loose semi-circle around the body. One of them bent and retched, while others cried out or moaned in terror. By then one of the campus security guards had reached the body and, shouting and waving his arms, began pushing the student athletes back.

Only Coach Pulaski, his face old and cracked as drying clay, refused to move. Merely stared down at the costumed body at his feet. His beefy frame slumped, as though having collapsed in on itself. Mouth chewing air, trying to form words.

“Jesus Christ.” His anguished whisper over my shoulder echoed my own horror as I crouched by the body. Forcing myself to look.

Almost immediately, I turned away, the bile rising in my throat. Willing myself, I swallowed a couple huge breaths. Trying to tamp down my fear, my revulsion. Then I caught sight of another security guard and motioned him to my side.

“Bend down across from me.” I managed to gesture across the body. “Help me shield him from onlookers.”

The man’s face was white as a paper plate, but he nodded and scrambled to the other side of the body. Keeping his own eyes averted from the fallen boy, he unzipped his coat and spread it wide behind him, like sheltering wings.

Steeling myself, I reached with both hands and gingerly peeled the torn, bloodied hood from the victim’s head. What came away with the ragged strips of cloth and plastic was a horrible mixture of brain, fleshy pulp and jagged shards of bone.

Gulping more frigid air, I struggled to comprehend what I was seeing. And holding in my cupped, trembling hands.

Seeping through the shredded cloth, dripping bright red droplets to the ground, was the shattered top of the victim’s head. Literally sheared off. Exposing a scalloped divot of scorched brain tissue, swimming in blood…

By now, more security had arrived. A quick backward glance revealed that they were having a hard time keeping the fans at a distance. A throng of people, varsity hand banners drooping at their sides, breaths misting in the biting cold, moved like a living thing toward the scene. I knew the overwhelmed guards wouldn’t be able to contain them for long.

Meanwhile, his own breathing quick and shallow, Dean Hobbs had finally joined me, falling to his knees beside the body.

“Poor kid. This will kill his parents. This will–”

His voice caught as he stared down at the dead boy. For the first time, I too registered the victim’s white, nondescript features. And received another shock.

It was perhaps the most horrific thing of all. A grotesque joke. A final, nightmarish touch.

Below the severed skull cap, rivulets of blood ran down the sides of an impossibly unmarred face. Like a manikin’s molded visage, the victim’s smooth, clean-shaven features looked essentially undisturbed. Frozen, lifeless, but obscenely intact. Lips slightly parted, as though about to speak. Eyes wide open, staring up at Hobbs and myself.

I took another deep breath to steady myself. The victim looked to be about the same age as the players themselves. What was the kid’s name again? Jason Something…?

Then the Dean made a strange, garbled sound. Peering down at the still, achingly young face, he blinked in confusion.

“What is it?” I gripped his arm.

He turned, aiming that same bewildered stare at me.

“This…I don’t know who it is…”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, this boy… he isn’t Jason Graham.”

Copyright © Dennis Palumbo. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.