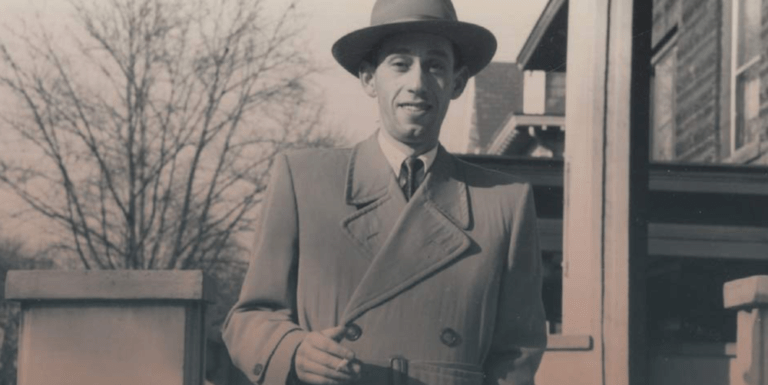

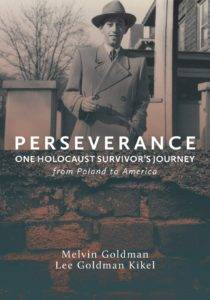

From the Publisher: “Melvin Goldman seemed to be a typical successful American, living with his family in Squirrel Hill, a multicultural Pittsburgh neighborhood with a large Jewish population. There, he turned his craftsmanship as a jewelry designer into a profitable business, and maintained a rosy outlook on life and a generous view of his fellow man. It may seem like a common story, but it is far from it. In the decade before his arrival in the United States in 1950, Mieczyslaw Goldman saw his home destroyed, his family torn apart, his health ruined, and nearly everyone he had ever known murdered in the death camps of the Third Reich. His survival of the years in the ghetto and Auschwitz, his long and slow recovery, and his attainment of a somewhat normal life are miraculous.

Perseverance witnesses the life and legacy of Melvin Goldman. Part One of the book, excerpted here, is in Goldman’s own words, assembled from the bits and pieces of his life he recorded in free moments in his Squirrel Hill jewelry store. In Part Two, Lee Goldman Kikel, Melvin’s daughter, recalls the happy life of a Squirrel Hill Jewish family, and pays tribute to a father who lived through unimaginable atrocities, but maintained his faith in God and humanity.”

“A tremendously stirring story . . . [told]through thick description of one Jewish man’s life in Poland, and later, in America following the Second World War. By situating this book in the details of the ‘local,’ the co-authors offer a personalized story of how the Holocaust unfolded in one man’s life and how that same man emerged with an outlook that was nothing less than amazing.” —Rabbi Aaron Benjamin Bisno, Rodef Shalom Congregation, Pittsburgh

“The premise of local history is that every story is worth telling, provided you have enough documentation to support it. Melvin Goldman did the hard work of creating and preserving that documentation, and his daughter, Lee, did the hard work of bringing it together into a narrative. The result is a local, individualized look at a communal experience. The section about Squirrel Hill is particularly valuable, as that story is only just beginning to be told in detail.” —Eric S. Lidji, Director, Rauh Jewish History Program & Archives, Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh, in association with the Smithsonian Institution

“Perseverance is the testimony of a Holocaust survivor and his daughter to one man’s journey and spirit. Melvin Goldman’s experience was in some ways typical of the torture and starvation by the Nazis, but it is also deeply particular and gripping. It is an inspiring book, a record of a life well lived after unbearable suffering and loss.” —Meredith Sue Willis, author, Out of the Mountains, Their Houses, and Oradell at Sea, among other books

From Chapter 1: My Beautiful Childhood Years…

Life in the wintertime is also beautiful. As in summer, Friday at noon the shop is closed, but my dad and the whole family dressed up for Friday night. There was a helper in the house who made potato soup or other soup. The main meal on Friday is going to be served in the evening after my dad comes home from the synagogue. My mother does her praying over the candles and we sat down for the Sabbath sacrament, which my dad would say, and drink the wine. Our Sabbath was performed in the normal Jewish traditional way. Then we enjoyed the delicious, well-prepared meal. During the holidays, we are very enthusiastic. We dress up especially in new clothes and shoes. We would also get extra things, like a soccer ball. Everyone is eager and animated.

Life in the wintertime is also beautiful. As in summer, Friday at noon the shop is closed, but my dad and the whole family dressed up for Friday night. There was a helper in the house who made potato soup or other soup. The main meal on Friday is going to be served in the evening after my dad comes home from the synagogue. My mother does her praying over the candles and we sat down for the Sabbath sacrament, which my dad would say, and drink the wine. Our Sabbath was performed in the normal Jewish traditional way. Then we enjoyed the delicious, well-prepared meal. During the holidays, we are very enthusiastic. We dress up especially in new clothes and shoes. We would also get extra things, like a soccer ball. Everyone is eager and animated.

From Chapter 2: The Germans March into Lodz

In Łódź, after the occupation of Poland, the Germans began to take away Jewish businesses. They confiscated everything from the Jews and relocated them to one small area of the city, which became the ghetto. During this process many were killed. Our rooms were demolished and our houses and property were taken away. They allowed five days to move all Jews, who didn’t already live within the confines of the ghetto, into the ghetto that will be closed in. My family was in with everyone else. Jews were formally sealed in on May 1, 1940. Electric wires were put up with German soldiers behind them, and nobody was allowed to go within fifty feet of the wires or they got shot.

The ghetto was about as large as a city area that could contain 50,000 people in the United States; there were 150,000 Jews in that ghetto in May 1940.

From Chapter 3: Prisoner 64227

I might have been frightened, but since I was with my brother, after the things we had gone through, I was okay. We were together, we shared. The procedure was that you got a small piece of mostly stale bread, and a little bit of soup, actually more water than soup. You had to catch it fast in a little hat, a cap that they handed you to wear. Either you burned your hands or your mouth, or you went hungry. That is how fast you had to get it. That is how you ate it. Besides the hat, the clothes you were given were like a blue- and-white striped pajama uniform and a pair of wooden shoes. That was the extent of the dress.

Going outside, you smelled something. You hadn’t been told yet, but you knew deep down that it was human flesh. We had been in Auschwitz for three days or so when the block leaders started pointing out the crematoriums. We saw the smoke, a constant dark billow from the smokestacks, and understood that we smelled the flesh and bones from the ovens. Sometimes even the ashes drifted down and settled around us like gray snow.

From Chapter 4: If I survive and live

I was given many, many transfusions. I remember getting them from an American nurse, a redhead, a wonderful person who was so often there. Off and on, I must have gone into a coma or something, and I know one thing—every time I opened my eyes she was there. They brought pajamas and dressings. They changed us two or three times a night. After a week or so they took X-rays of me and said I had a collapsed lung. Of course, it has to be realized that we were like ninety-year-old people, with everything gone. They washed us, changed our clothes—so much care we received. They were absolutely marvelous, those nurses. During that time I started to hope.

The Americans were holding German prisoners in that hangar. They put red crosses on their backs so we knew who they were. They were used as laborers in order to help us, the refugees, or whatever you call the people from concentration camps. One American, he told me he was Greek, came over and through translation gave me a shaving kit. But I couldn’t shave; I couldn’t move my arms. I was too weak to shave or do much of anything. It was a beautiful gesture though. He hugged me and kissed me. They were marvelous, these people.

From Chapter 5: My Will Was Strong

Remember, I lost my youth at sixteen locked into a ghetto, then death camps, and got out in my early twenties. I could not yet make it as a normal person doing normal activities. It took me a long while until I got the courage, plus the will and a drop of better health, to dream of going out on a date. I hadn’t lost some of the apprehension of going and coming. Eventually, I did have the courage to go out. The worst way, even walking a block, took me approximately two and a half hours. I was determined to walk and to live as normal as the people on the outside. Everything was wrong inside my body. That was the consolation—outside, if you dressed, nobody knew what was bothering you or how sick you were. At least we lived, and we tried to recover our health.

From Chapter 6: I was Going To Make It

We were on the ship Christmas night. The crew had a party, but the boat was rocking, and only a few of us could manage to eat or dance. We didn’t have much. We had no money and not much luggage, no special possessions, but deep down we knew we were going to a country that wanted us, where people will help us. The mood was happy, very happy. At last, one day we looked out and saw the Statue of Liberty. Man, woman, or child, you realize, after all the things you have gone through, you have finally reached the United States of America.

From Chapter 7: Looking Back, Looking Forward

I would like to say that now my dream did come true. I have a family. I have a nice daughter. And I do have a business. I hope that we are all well. With all the things we went through here, sicknesses, like a normal average person, and everything else, thank God we are very happy. We have a house. I’m here now almost three decades, and I feel like it is my home. I would fight and do anything for this country and this home. And I can say one thing for sure, “I am delighted to be here as a citizen.” I feel no other than as an American, that’s all.

This excerpt from Perseverance: One Holocaust Survivor’s Journey from Poland to America is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reproduced without permission.