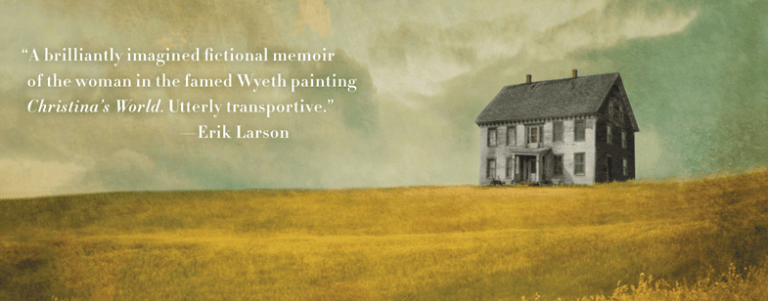

From the #1 New York Times bestselling author of the smash bestseller Orphan Train, a stunning and atmospheric novel of friendship, passion, and art, inspired by Andrew Wyeth’s mysterious and iconic painting Christina’s World.

“Graceful, moving and powerful.” — Michael Chabon, New York Times bestselling author of Moonglow

Don’t miss out: Christina Baker Kline will be at Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures on March 1st!

From the publisher: “In her new novel, Kline turns her attention to another little-known part of America’s history: the story of Christina Olson, the complex woman and real-life muse Andrew Wyeth portrayed in his 1948 masterpiece Christina’s World. The painting — which features a mysterious woman in a pink dress sitting in a field, gazing at a weathered house in the distance — is an iconic piece of American art and hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City as part of their permanent collection.

In A Piece of the World, Kline vividly imagines the life of Christina Olson. Born in the same remote farmhouse in Cushing, Maine that her family had lived in for generations, and increasingly incapacitated by a degenerative muscular disorder that made it difficult to walk, Christina seemed destined to lead an uneventful life. Her fate changed the day 22-year-old Andrew Wyeth knocked on her front door.

Told in evocative and lucid prose, A Piece of the World is a story about the burdens and blessings of family history, and how artist and muse can come together to forge a new and timeless legacy…”

PROLOGUE

Later he told me he’d been afraid to show me the painting. He thought I wouldn’t like the way he portrayed me: dragging myself across the field, fingers clutching dirt, my legs twisted behind. The arid moonscape of wheatgrass and timothy. That dilapidated house in the distance, looming up like a secret that won’t stay hidden. Faraway windows, opaque and unreadable. Ruts in the spiky grass made by an invisible vehicle, leading nowhere. Dishwater sky.

Later he told me he’d been afraid to show me the painting. He thought I wouldn’t like the way he portrayed me: dragging myself across the field, fingers clutching dirt, my legs twisted behind. The arid moonscape of wheatgrass and timothy. That dilapidated house in the distance, looming up like a secret that won’t stay hidden. Faraway windows, opaque and unreadable. Ruts in the spiky grass made by an invisible vehicle, leading nowhere. Dishwater sky.

People think the painting is a portrait, but it isn’t. Not really. He wasn’t even in the field; he conjured it from a room in the house, an entirely different angle. He removed rocks and trees and outbuildings. The scale of the barn is wrong. And I am not that frail young thing, but a middle-aged spinster. It’s not my body, really, and maybe not even my head.

He did get one thing right: Sometimes a sanctuary, sometimes a prison, that house on the hill has always been my home. I’ve spent my life yearning toward it, wanting to escape it, paralyzed by its hold on me. (There are many ways to be crippled, I’ve learned over the years, many forms of paralysis.) My ancestors fled to Maine from Salem, but like anyone who tries to run away from the past, they brought it with them. Something inexorable seeds itself in the place of your origin. You can never escape the bonds of family history, no matter how far you travel. And the skeleton of a house can carry in its bones the marrow of all that came before.

Who are you, Christina Olson? he asked me once

Nobody had ever asked me that. I had to think about it for a while.

If you really want to know me, I said, we’ll have to start with the witches. And then the drowned boys. The shells from distant lands, a whole room full of them. The Swedish sailor marooned in ice. I’ll need to tell you about the false smiles of the Harvard man and the hand-wringing of those brilliant Boston doctors, the dory in the haymow and the wheelchair in the sea.

And eventually—though neither of us knew it yet—we’d end up here, in this place, within and without the world of the painting.

1939

I’m working on a quilt patch in the kitchen on a brilliant July afternoon, small squares of fabric and a pincushion and scissors on the table beside me, when I hear the hum of a car engine. Looking out the window toward the cove, I see a station wagon turn into the field about a hundred yards away. The engine cuts off and the passenger door swings open and Betsy James gets out, laughing and exclaiming. I haven’t seen her since last summer. She’s wearing a white halter top and denim shorts, a red bandanna tied around her neck. As I watch her coming toward the house, I am struck by how different she looks. Her sweet round face has thinned and lengthened; her chestnut hair is long and thick around her shoulders, her eyes dark and shining. A red slash of lipstick. I think of her at nine years old, when she first came to visit, her small, nimble fingers braiding my hair as she sat behind me on the stoop. And here she is, seventeen and suddenly a woman.

“Hey there, Christina,” she says at the screen door, out of breath. “It’s been such a long time!”

“Come in,” I say from my chair. “You won’t mind if I don’t get up?”

“Of course not.” When she steps inside, the room smells of roses. (When did Betsy start wearing perfume?) She sweeps over to my chair and hugs my shoulders. “We arrived a few days ago. I surely am happy to be back.”

“You surely look it.”

She smiles, spots of color on her cheeks. “How are you and Al?”

“Oh, you know. Fine. The same.”

“The same is good, yes?”

I smile. Sure. The same is good.

“What are you making here?”

“Just a little thing. A baby quilt. Lora’s pregnant again.”

“Such a generous auntie.” She reaches down and picks up a quilt square, a piece of calico, pink flowers with green leaves on a brown background. “I recognize this fabric.”

“I tore up an old dress.”

“I remember it. Small white buttons and a full skirt, right?”

I think of my mother bringing home the Butterick pattern and the iridescent buttons and the calico. I think of Walton seeing me in the dress for the first time. I am awed by you. “That was a long time ago.”

“Well, it’s nice that old dress is getting a new life.” Gently she places the square back on the table and sifts through the others: white muslin, navy cotton, chambray faintly marked with ink. “All these bits and pieces. You’re making a family heirloom.”

“I don’t know about that,” I say. “It’s just a pile of scraps.”

“One man’s trash . . .” She laughs and glances out the window. “I completely forgot! I came up here for a cup of water, if you don’t mind.”

“Sit down, I’ll get you a glass.”

“Oh, it’s not for me.” She points at the station wagon in the field. “My friend wants to paint a picture of your house, but he needs water to do it.”

I squint at the car. A boy is sitting on the roof, looking at the sky. He’s got a large white pad of paper in one hand and what looks like a pencil in the other.

“He’s N. C. Wyeth’s son,” Betsy says in a stage whisper, as if someone might hear.

“Who?”

“You know N. C. Wyeth. The famous illustrator? Treasure Island?”

Ah, Treasure Island. “Al loved that book. I think we still have it somewhere.”

“I think every boy in America has it somewhere. Well, his son’s an artist too. I just met him today.”

“You met him today, and you’re riding around in a car with him?”

“Yes, he’s—I don’t know. He seems trustworthy.”

“Your parents don’t mind?”

“They don’t know.” She smiles sheepishly. “He showed up at the house this morning looking for my father, but my parents had gone off for a sail. I answered the door. And here we are.”

“That happens sometimes,” I say. “Where’s he from?”

“Pennsylvania. His family has a summer place up here, in Port Clyde.”

“You seem to know an awful lot about him,” I say, arching an eyebrow.

She arches an eyebrow back. “I plan to learn more.”

Betsy leaves with her cup of water and makes her way back to the station wagon. By the way she’s walking, shoulders back and chin forward, I can tell she knows he’s watching her. And she likes it. She hands the boy the cup and climbs onto the roof next to him.

“Who was that?” My brother Al is at the back door, wiping his hands on a rag. I can never tell when he’s coming; he’s as quiet as a fox.

“Betsy. And a boy. He’s painting a picture of the house, she said.”

“Why would he want to do that?”

I shrug. “People are funny.”

“Sure are.” Al settles into his rocker, pulling out his pipe and tobacco. He starts tamping and lighting, both of us spying on Betsy and the boy out the window and trying to act like we aren’t.

After a while the boy climbs down and sets his pad of paper on the hood of the car. He offers his hand to Betsy, who slides down into his embrace. Even from this distance I can feel the heat between them. They stand there talking for a minute, and then Betsy tugs on his hand, pulling him toward—oh

Lord, she’s bringing him up to the house. I feel a momentary panic: the floor is dusty, my dress soiled, my hair unkempt. Al’s overalls are splashed with mud. It’s been a long time since I’ve worried about being seen through the eyes of a stranger. As they walk toward the house, though, I see the boy gazing at Betsy and realize I don’t need to worry. She is all he sees.

He’s at the screen, now, on the threshold. Lanky, smiling, quivering with energy, he fills the entire doorway. “What a marvelous house,” he murmurs as he opens the screen, craning his neck to look up and around the room. “The light in here is extraordinary.”

“Christina, Alvaro, this is Andrew,” Betsy says, coming in behind him.

He inclines his head. “Hope you don’t mind my crashing in uninvited. Betsy swore it was okay.”

“We don’t stand on ceremony,” my brother says. “I’m Al.”

“People after my own heart. And call me Andy, please.”

“Well, I’m Christina,” I say.

“I call her Christie, but no one else does,” Al adds.

“Christina, then,” Andy says, settling his gaze on me. I detect no judgment in it, only a kind of anthropological curiosity. Still, his keen attention makes me blush.

Turning to Al, I say quickly, “Remember that book Treasure Island? His father did the paintings for it, Betsy said.”

“Did he now?” Al’s face lights up. “You can’t forget those pictures. I probably read that book a dozen times. Might be the only book I ever actually finished, now that I think about it. I wanted to be a pirate.”

Andy breaks into a grin. His teeth are large and white, like a movie star’s. “So did I. Still do, in fact.”

Betsy’s holding the oversized drawing pad. As proud as a new mother, she brings it over to show me. “Look what Andy did, Christina, in that short amount of time.”

The paper is still damp. In bold strokes Andy reduced the house to a white box with two gables facing the sea. The fields are green and yellow, with bristly blades of grass poking up here and there. Near-black firs, a purple swipe of mountains, watery clouds. Though the watercolor has been done quickly—there’s movement in the brushstrokes, as if the wind is blowing through—it’s clear this boy knows what he’s doing. The windows are mere suggestions, but you have the peculiar sense that you can see inside. The house seems rooted in the earth.

“It’s just a sketch,” Andy says, coming up beside me. “I’ll keep working at it.”

“Looks like a nice place to live,” I say. The house is snug and cozy, a fairy-tale version of the one Al and I actually live in, the only hint of its decay in smudges of blue and brown.

Andy laughs. “You tell me.” Running two fingers over the paper, he says, “Such stark lines. There’s something about this place . . . You’ve lived here a long time?”

I nod.

“I sense that. That it’s a place filled with stories. I’ll bet I could paint it for a hundred years and never get tired of it.”

“Oh, you’d get tired of it,” Al says.

We all laugh.

Andy claps his hands together. “Hey, guess what? Today is my birthday.”

“Is it really?” Betsy asks. “You didn’t tell me.”

He puts his arm around her and tugs her toward him. “Didn’t I? I feel like you know everything about me already.”

“Not yet,” she says.

“What’s your age?” I ask him.

“Twenty-two.”

“Twenty-two! Betsy’s only seventeen.”

“A mature seventeen,” Betsy blurts, color rising to her cheeks.

Andy seems amused. “Well, I’ve never cared much about age. Or maturity.”

“How are you going to celebrate?” I ask.

He raises an eyebrow at Betsy. “I’d say I’m celebrating right now.”

This excerpt from A Piece of the World is published here courtesy of William Morrow (HarperCollins). Copyright © 2017 by Christina Baker Kline.