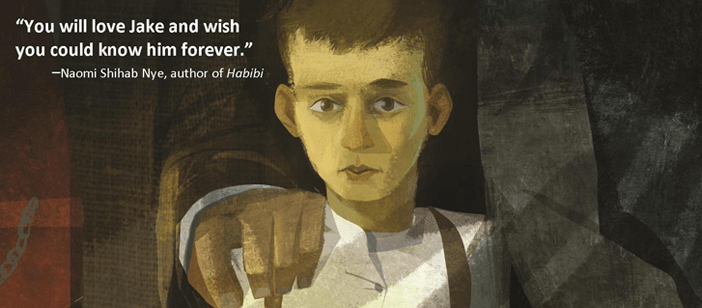

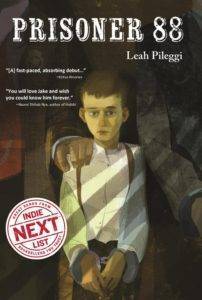

Prisoner 88 — the award-winning historical novel by local author Leah Pileggi — is out in paperback from Charlesbridge publishers this month and to celebrate we’re excited to feature the first chapter right here on Littsburgh!

From the Publisher: “What if you were ten years old and thrown into prison with hardened criminals? That’s just what happens to Jake Oliver Evans. Inspired by a true account of a prisoner in the Idaho Territorial Penitentiary in 1885, Jake’s story is as affecting as it is shocking…

Leah Pileggi introduces a strong yet vulnerable character in an exciting and harrowing story of a child growing up on his own in America’s Old West.”

For more about Pileggi’s forthcoming projects, be sure to connect with her on Facebook and Twitter!

Chapter 1

May 31, 1885 – The Idaho Territory

Back before I shot Mr. Bennett, most every day was ‘bout the same. Do what Pa said, work when I had to, eat when I could, sleep somewhere, start again when the sun come up. But after I got arrested, I didn’t have Pa to listen to no more. He wasn’t going to prison. Just me. Being that I was already ten and some, I figured I could pretty much take care of myself.

Back before I shot Mr. Bennett, most every day was ‘bout the same. Do what Pa said, work when I had to, eat when I could, sleep somewhere, start again when the sun come up. But after I got arrested, I didn’t have Pa to listen to no more. He wasn’t going to prison. Just me. Being that I was already ten and some, I figured I could pretty much take care of myself.

I hadn’t never been on a train before. I stretched my neck tall to see out that train window. What I really wanted was to get on my knees and look out on the whole big world going by. But it was hard to move around wearing them big old rusty handcuffs, and one of the guards woulda smacked me. Alls I could see anyways was black smoke blowing back from that loud coal engine.

There was four of us criminals. Me and two guys and one Chinaman. The Chinaman wore black pants, a black shirt, and a long tail braid down his back. The old guy with the beard wore a white shirt, jacket, and tie, but the ugly old guy wasn’t wearing much more than rags.

We didn’t say nothing on that train ride, ‘cause we woulda got smacked for that, too. Right at the start the tall guard with the long mustache said, “Set down and shut up,” and I wasn’t taking no chances, ‘cause I believed him and his rifle. The other guard, the fat one with the red face, him and his Winchester didn’t say not one word the whole way.

We got off the train in Boise, me and them three other men and them two guards. People stared at us shuffling along, our chains clanking and us looking all tough and mean.

Some train men lifted our belongings on top of a stagecoach. The beard man and the Chinaman had trunks. Not the ugly man and not me. I just had a old canvas bag, and he didn’t have nothing. The red-face guard set inside, right between me and the window. The mustache guard set up front with the driver. I hadn’t never been in a stage before either. Even with the windows open, it was rough riding and hot and smelly like to choke us all. I couldn’t see nothing but the nasty rotten teeth on the ugly man setting across from me.

When the stage stopped, Mustache and Red Face pulled us out. We was all met by a couple more guards, both holding rifles in their two hands. We was facing a big old round-top wood gate set in a high white stone wall. On one side of the gate, that stone wall kept going. But on the other side, the stones met up tight with a high wood fence. One of them new guards, a young guy with a bunch of orange hair, seen me looking.

“The whole fence used to be wood,” he said. “They’re bringing in stone to finish it out.”

I looked out beyond the wood section. Patches of scrub grass led up to the top of a steep hill where a cross pointed to the sky. I turned in a slow circle. Hills rolled up around us on most sides, like we was stew dregs in the bottom of a giant bowl.

The Mustache unlocked the gate. “Move it,” he said. The guards pushed us through and locked the gate behind us.

We was led across a stretch of dirt toward a stone building. Bars covered the windows, and a long wire run from one of them windows across to what I figured out was the cellblock. We four men and four guards moved all clumped together into the building and down a hallway, and then we packed tight near the doorway of some special room. I knew it was special ‘cause after our footsteps stopped making noise, it was so quiet I could hear my own heart beating in my ears.

A voice boomed, “Welcome to the Idaho Penitentiary, gentlemen.”

Made me jump. Some hand come down on my shoulder to keep me in place. I couldn’t see who was talking ‘cause I was right up against the Chinaman’s black shirt.

“I am Mr. Norton, assistant warden,” said the big voice. “The door behind me leads to Warden Johnson’s office. It’s up to me to see to it that you do not end up in there during your incarceration.” He grunted. “You will answer a list of questions for me before you’re taken away. Otherwise, you will not talk, you will not move, you will not make a sound.” I heard a thump and then papers flapping, like a big book flopped open. Then he barked, “You.”

The first man shuffled on into the room.

“Prisoner number 85. Name?”

“Albert Meecham.”

Sounded like he had a old dried-up frog in his throat. Had to be the ugly man.

“Age?”

I sorta drifted off about then, being kinda tired from the trip. I didn’t listen again ‘til Mr. Norton shouted, “Speak up, Mr. Meecham.”

“Murder in the first degree” is what he said.

Then Mr. Norton’s voice got kinda quiet and real deep. “Those handcuffs and Leininger shackles will become your close friends, Mr. Meecham. When you are out of your cell—if you are out of your cell—they will be with you every second.”

Mr. Meecham didn’t have nothing to say to that.

Mr. Norton kept on talking. “If at any time the warden or I feel that you are a threat to the guards or to the other inmates, you will be placed in the Hole. That’s solitary confinement, sir.”

I heard Mr. Norton cough up a wad of spit and let it go into some kinda container. Then he went right on talking. “The Hole’s an unpleasant place to pass the time, Mr. Meecham. Do you understand?”

I heard, “Yeah.”

“What did you say?”

Mr. Meecham’s gravelly voice growled, “Yes, sir.”

There was some scuffling, and then here come the ugly man with two guards holding him under his armpits. He grinned at me with them dead teeth as they took him out. Last thing I seen was his boot toes dragging behind him.

“Next,” said Mr. Norton.

I could hear the beard man’s arm irons clanking as he stepped ahead.

“Prisoner number 86,” said Mr. Norton. “Name?”

“Joshua Nance.”

“Age?”

“Sixty-two.”

“Height?”

I heard some boots moving around, and one of them guards said, “He’s round about six feet.”

“Skin color?”

“Well, sir, if I could remove the travel dirt from my face and neck, you’d see that I’m a white man.”

Mr. Norton said, “Did I ask for a story, Mr. Nance?”

“No, sir.”

“That’s ‘light’ for complexion. Occupation?”

Mr. Nance cleared his throat real quiet. “Rancher.”

“The crime of which you were convicted, Mr. Nance?”

“Unlawful cohabitation.”

“One of those Mormon cohabs, is that right, Mr. Nance? How many wives you got, sir?”

Mr. Nance didn’t say nothing.

“Looks like you know how to keep your mouth shut,” said Mr. Norton. “I expect you’ll conduct yourself well here, Mr. Nance, seeing as you’re not a violent criminal.”

“I will,” said Mr. Nance.

A guard pulled him by the arm past me. The two of them turned the corner and was gone. A couple more guards come in and pushed by.

Next was the Chinaman, who was standing right in front of me. He just stayed right where he was.

“Prisoner number 87. Name?” said Mr. Norton. He didn’t get no answer. He shouted, “Name?”

The man’s answer sounded like “Shin Han.”

“Yes, well,” said Mr. Norton. “So you’ve learned some English. Isn’t that an amazing feat.” He grunted again. “Age?”

“Twent-four.”

“Height? I’ll say five foot six.”

I leaned just a little bit around Mr. Han and looked with ‘bout one eyeball, and I could sorta see Mr. Norton by that time. He was a mountain of a man, and he was setting behind a desk and writing in a big old book.

“Complexion is olive,” said Mr. Norton out loud to hisself while scribbling in his record book. “And no occupation.”

But Shin Han said, “Merchant and muse.”

Mr. Norton snapped, “‘Merchant’ I get. What’s ‘muse’?”

Even with his hands chained up together, and me still looking at his back, I could tell Shin Han was showing he could play a instrument with strings.

“Musician,” said Mr. Norton. “Not ‘muse.’ Musician.”

“Yes,” said Shin Han. “Musician.”

“Well,” said Mr. Norton. “We’ll expect you to entertain us, Mr. Han. You just better be telling the truth.”

Shin Han nodded. “Yes. I tell truth. I play musician.”

Grunt. “You were convicted of assault, Mr. Han. You step out of line and you’ll end up in the Hole. Do you understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

A guard turned him around and pushed him by me just when Mr. Norton said, “Next!”

Being the only one left, I kinda lurched forward into the room. Even though Mr. Norton was setting, he still had to look down at me. “You’re Mr. Jake Oliver Evans.”

How did he know? I said, “Yes, sir.”

He was writing in his big book. “You are now officially prisoner 88 of the Idaho Territorial Penitentiary.”

Was I a number now instead of a name? I opened my mouth to ask him, but Mr. Norton, with arms like logs, leaned forward. “Says you’re in here for manslaughter. Is that so.”

“Yes, sir. Well, that’s what they said. . . .”

“I thought this was a mistake,” said Mr. Norton, “sending us a kid out here.” He picked through some papers and then held one up. “You got five years?”

I lifted my hands with them cuffs on, trying to scratch at my head. I told him, “Ain’t no mistake, mister. It’s me.”

He kinda squinched up his eyes like he didn’t much like me.

“Height?”

A guard, the one with the orange hair, measured me, using a tall piece of wood. “Four foot six,” he said.

Mr. Norton wrote it down. A fly buzzed across the room, and he swatted at it. Then he crossed his arms and looked me clean in the face. “Well, now, where are we supposed to put you?”

“In one of them cells,” I said. “Ain’t that right?”

“You got a quick mouth, don’t you, son?”

I looked at the floor. Pa used to say that, and then he’d knock me good.

Mr. Norton shook his head. “Well, looks like you’ve got it all figured out, Mr. Jake Oliver Evans.”

I told him, “I reckon.”

Mr. Norton snorted. “You better hope so.” He turned to the orange-haired guard. “For now he’s got a fancy room all to himself. On the top, Henry. First cell.”

Henry nodded, a bunch of that orange hair flopping around.

I was gonna be on the highest-up place in the building. That was great. I liked looking out and down on things, like when I climbed a barn where Pa and me was supposed to be tending pigs. I fell off the roof and broke this left arm. That’s why it don’t hang straight. But I seen a long way off from that roof.

Mr. Norton kept on talking. “This place was built for one inmate in a cell. But we have too much lawlessness since the gold rush. We’ve got twice the bad men we’re supposed to have. So you just feel real lucky that you have a cell all to yourself.”

“Yes, sir.”

“But don’t count on that lasting.”

“No, sir.”

Henry led me by my crooked arm around the corner to a heavy door. He unlocked it and then locked it back up behind us. His ring of keys clinked and my handcuffs clunked when we crossed the dirt yard. It was baked hard as a rock from the sun. We walked up three stone steps to a all-white stone building. Then Henry unlocked the door to the cell block and walked me into my new home.

Excerpted from PRISONER 88 by Leah Pileggi. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without their permission.