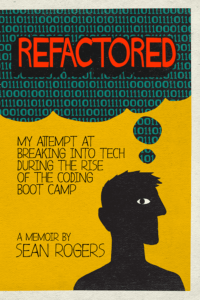

From the Publisher: “Thirty-nine years old, laid off from a bookstore, and working in the backroom of a grocery, Sean Rogers thought the time was right to start his career as a software developer. The only problem: he knew nothing about technology. Just the opposite, he held on to CD players and flip phones long past the point of prudence.

Enter Tech Elevator (in Pittsburgh), an in-person coding boot camp boasting a 92% job placement. Welcome to 14 weeks of intensive education, larger-than-life characters, and a bumbling yet inspiring attempt at becoming a programmer.

As more people than ever begin looking for new careers, interest in coding boot camps has surged as a replacement for the traditional four-year degree. Refactored: My Attempt at Breaking into Tech During the Rise of the Coding Boot Camp is a wild, funny, stressful insider’s look on a movement that is changing the face of education the world over….”

About the Author: Sean Rogers is a writer and software developer living in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Chapter One

I’ve always wanted to be smart. In their twenties, people spend a lot of time trying to appear cool or artsy or cultured. And I tried to be those things too, I’m not denying it. But really, deep down, I just wanted people to think I was smart. I still do. In my greatest fantasies, someone walks away from a conversation with me and tells their friend, “That guy is really smart.” The friend nods in agreement, looking back with a mixture of awe and jealousy at my cool, effortless acumen.

I’ve always wanted to be smart. In their twenties, people spend a lot of time trying to appear cool or artsy or cultured. And I tried to be those things too, I’m not denying it. But really, deep down, I just wanted people to think I was smart. I still do. In my greatest fantasies, someone walks away from a conversation with me and tells their friend, “That guy is really smart.” The friend nods in agreement, looking back with a mixture of awe and jealousy at my cool, effortless acumen.

To be clear, that doesn’t happen. And it never will.

But I do know a lot about books, and knowing a lot about books makes it easier to dupe people into thinking you’re smart. Being up-to-speed on the literary scene, you acquire arrays of information in small tidbits. These pebbles of information, judiciously cobbled in conversation, can often be enough to build a facade of high intelligence. I’ve become skilled at this trick, mainly because I had so much time to practice it. I worked in a bookstore for sixteen years. Among other factors, my desire to appear smart kept me in the bookstore over the long haul. And later, that same desire drove me to take the biggest risk of my life—going into considerable debt and pushing myself and my family to the brink of stressful chaos in an attempt to roughhouse my way into the world of computer software.

But let’s back up. I began working at Barnes & Noble in the winter of 2002 shortly after exiting a hellish copywriting position in Secaucus, New Jersey. I was out of college six months and had already quit my first job.

I wanted to write fiction. Knowing I couldn’t make any money writing fiction, I took a job at the Flatwater, New Jersey Barnes & Noble making a quarter above minimum wage. I worked there less than a year and then transferred across the Hudson into New York, to Forest Hills, Queens, where I became a manager. I stayed in New York for about five years and then moved back to Pittsburgh, where I had grown up. I was newly married, set on buying a house, starting a family, and writing the novel that would get my name on a bookshelf and prove, beyond question, that I am smart.

I was set. I didn’t make much money during those sixteen years (at the lowest $7.25 an hour and $20 at the height), but I didn’t really care. While my friends bemoaned their vampiric jobs, I alone stated that I would happily work at Barnes & Noble until retirement. I meant it.

Glenn, the store manager of Barnes & Noble Bethel Park, paged me from the receiving room on Monday morning. I knew something was wrong by the tone of his voice. We weren’t friends, exactly, but we got along well and respected each other. He was red-eyed and haggard as I entered the office. He closed the door behind me.

I tried to remember if there was any misdeed I had committed that would call for a closed-door discussion. Did I make a joke that offended someone, I wondered. Had I taken an advance copy that I actually should have paid for? Was there something—some mistake—that I could clarify for Glenn and make his dour expression soften?

“Barnes & Noble is laying people off.”

I raised my eyebrows.

“Really?” I prodded, not certain if he was laying me off or asking me to help him lay off others. Both options were horrid.

“Restructuring. Your whole position is being taken away,” he said quietly. His red eyes were wet now. He looked at the wall behind me. “I’m really sorry about this.”

My face pin-prickled. There was a sense of surreality.

“And they don’t want to move me to another position?” I asked. I didn’t want to make this harder on Glenn than it had to be, but come on. I was an excellent employee. “I’m coming off of two ‘Exceeds Standards’ reviews.”

“Yeah, no,” he mumbled. “It’s just laid off.”

Glenn went on to explain about severance and extended health care and that he would be a reference for whatever job I moved onto. I ended the conversation as quickly as I could. I retrieved my coat, the book I was reading, and my lunch, uneaten, packed an hour before. Glenn stayed in the office while I gathered my things; I was saved the indignity of being escorted from the building. As I exited through the double doors I heard Glenn page Betsy, the next in line for his sad hatchet job.

I called my wife from the car.

“What’s up?” Jenny asked.

“I just got laid off.”

I’ve always been a pull-the-bandaid-off kind of guy.

“What?”

“I got laid off,” I said again.

It sounded like a joke or a lie. I didn’t quite believe it myself. I was thirty-eight years old and had been at the job since I was twenty-three.

“Really?”

“Yeah. I’m coming home.”

When I got home, the embarrassment set in. This job, which I liked but wasn’t necessarily proud of, didn’t value me. They viewed me as excess, best to be disposed. In short, I wasn’t good enough for the bookstore.

I had to tell Afton, my seven-year-old daughter, when she got home from school. She tried to joke around about it, a trait of Jenny’s that she did her best to mimic, but I wasn’t in the mood. I reacted sullenly and she wandered off to play Barbies, resurfacing just before dinner to inquire whether we were now poor.

The severance that Glenn had mentioned was pretty good. I was given sixteen weeks of full pay, one for each year of service. There was time.

After some careful consideration about my next move, I decided to dedicate a week to completely flipping out. I didn’t sleep, exercised excessively, and nervously clicked through the Internet for long stretches. It was nice.

I rewrote my resume for hours on end, wondering how much lying I could get away with. I scoured the job boards online; wrote to friends on Facebook whom I hadn’t contacted in years. I spent every second of the day thinking about how I was going to make money. I considered freelance writing, working as a test driver of automated cars, getting a job at another bookstore, substitute teaching, being a ranger at a national park, learning how to be a roofer, and becoming a ringside judge for boxing and mixed martial arts. You know, all the grounded, reasonable career paths that anyone would look into when choosing a new line of work.

Before I applied to this motley lineup of positions, a few friends called with offers at their places of work. They were shitty jobs, every last one of them, but their very existence had a calming effect. After some serious drinking, I came to understand that I would be able to get back into the workforce whenever I chose. I would only be unemployed for as long as I cared to be unemployed. With this realization came a query I hadn’t previously considered: When am I ever going to get four months of full pay and no work? Answer: never again. I then made a decision that set my mind at ease. I would not even think about getting a job for a couple months, work on my novel, and take it easy.

And that’s what I did. I had about one hundred pages of a fantasy novel I had started some years before, and between February and May of 2018 I pushed that tally over five hundred. Pretty good work.

A friend of mine and ex-Barnes & Noble employee had been made the director of a new grocery store opening in Pittsburgh. Green Basil, it was called. He had written to me on Facebook offering a job a few times, and as my walkabout months drew to a close, I accepted.

I had had a theory, ever since quitting that hellish copywriting job in Secaucus all those years ago, that I didn’t much care to have a big and important job; a job that would rake in the dough but stress me out. For me, a regular job wasn’t my path to success. I needed all of my brain waves saved up so that I could write full force. And I kept this theory alive as I went into the grocery business. The plan was to show up every day, do my work, and then return home in the early afternoons with plenty of time and plenty of mental fortitude with which to write the great American novel. Sure, it wasn’t the bookstore, but it was simple, honest work. How bad could it be?

Answer to that question? Really bad.

Look, Green Basil is a perfectly good grocery store and I’m not saying you shouldn’t buy your food there. But I am, with deadly seriousness, advising you not to work there.

I was the receiving manager, the same position that I had held at Barnes & Noble for the last few years of my employment. I was given a cache of bright green shirts that I had to wear every day, even though I was not customer-facing. The shirts had the Green Basil emblem on the front, a yellow plaque stating the name of the store accompanied by a silhouetted farmer atop a tractor, and corny phrases such as “Let the good Thymes roll” and “I yam what I yam” written across the back.

The job wasn’t great for my self-image. I try not to tie my ego to my work, but this effort is not always successful. When I moved back to Pittsburgh in 2008, one of my biggest misgivings was telling people that I worked at Barnes & Noble or, God forbid, running into old acquaintances at the store while I was working. I’m aware that I’m sort of an asshole for feeling this way. Barnes & Noble was a perfectly fine job. I’ve already stated emphatically that I enjoyed being employed there. But some vain recess of my soul whispered that I was somehow above that station, despite all visible proof. This isn’t what a smart person does for a living, the vain voice told me.

I climbed past this personality defect long before February 2018, when I was laid off. Sometime after the birth of my daughter, I found a well of self-respect that came from a more primal place. Having a child spawned the acceptance and realization that I was a grown man, and my misgivings about my place in the world fell away for the most part.

But still. Driving back from a weekend in Toronto with two of my friends, at the border, the officer wanted everyone in the car to say what they did for a living. “I teach history,” Mike said. “I’m a director for the Red Cross,” Tim replied. “I work at a grocery store,” whispered Sean, red with bruised vanity.

I yam what I yam.

At Green Basil, I spent the days unloading trucks into the back room and squeezing thousand-pound palettes of Fuji apples, Rainier cherries, and Barlett pears into the produce cooler. I delved into the freezer a dozen times a shift, an arctic locker so cold that your nose hairs froze with each breath. I choked back vomit as I chucked outdated rotisserie chickens down the garbage shoot, knowing that I would live with the smell of putrefying flesh until the dumpster was changed out on Friday.

When I wasn’t cramming food into every centimeter of the back room, I was furiously inputting manifests of the deliveries into the early 90s spreadsheets that Green Basil ran its business on. I stared into the white screen, flies landing on my face like I was one of those poor children from the Sally Struthers infomercials, focusing with all my might to work typo-free, knowing that I would have to start typing the long columns of product numbers all over if the totals didn’t add up at the end.

I went home each day dirty, the smell of rotting fruit and cow blood in my nose, and mentally exhausted. The writing did not go well that spring.

It might not seem like it from what you’ve read thus far, but I can be tiresome with my positivity. Not all the time, mind you, but some of the time. There are areas in my life where I have turned a blind eye to the negative aspects and smiled my way through, citing hard work and a good attitude as an eventual savior. And that’s what I was doing in June 2018.

“It’s fine,” I said to Jenny after a ten-hour day spent typing manifests into spreadsheets.

“It’s okay,” I reported, following an afternoon of lifting damp turkeys, dripping with plasma, from their cardboard crates.

“I think I can keep doing this,” I insisted, having discovered a slew of maggots in my sock after a shift of wrestling with the broken trash compactor.

One particularly trying day, I was in the back room when I heard someone beating against the wall. I stopped what I was doing and listened. It was almost tribal, the beat, something I had heard in the New York subway systems from the men with plastic buckets upturned. Then someone screamed.

It was beastial, this scream. As if a god had died.

I ran to the bathroom and dashed through the swinging door. The drumming had begun again. Someone was in the stall, the door locked. I waited in horror, watching myself in the mirror of the restroom, as the redoubtable beat echoed across linoleum.

“Excuse me…?” I tested.

The drumming stopped.

“Are you all right?” I asked.

“Mmmmm …I’m fine.”

The voice was deep and gargled, but I recognized it as belonging to Bobby, the new produce guy, part time.

“Do you need help or anything?”

“…nope. Fine.”

Bobby was supposed to start work in fifteen minutes and had, it turned out, decided to ingest heroin in the bathroom beforehand. High out of his mind, he had been drumming on the toilet lid.

“I’m going to need to find another job,” I told Jenny that evening.

But what to do?

I thought that working at Green Basil might be similar to the back room at Barnes & Noble—the trucks, the solitude, the lack of customers. But it wasn’t. I was at Barnes & Noble for the books, not because I had a driving passion about shipping and receiving. All of my skills were in retail management and I did not want to do retail management if it didn’t have to do with books. So what could I do?

I struggled with this question. All I really wanted to do was write, but in sixteen years of writing I had made approximately six thousand dollars through publications. That probably wouldn’t cut it, budget-wise.

Once, in my late twenties, when I was thinking about leaving Barnes & Noble, I had the wild idea to go back to school and become a math teacher. I am not good at math. And I don’t particularly like it. But, to me, there was something romantic about attacking my weak point, hammering at it until it became a strength. I actually looked into what type of schooling I would need to make this path doable. It was a long road for someone with an English degree and the idea faded away.

But that same romantic feeling hit me again in July 2018 while driving to my parents’ house for dinner. Tech Elevator, a coding boot camp new to Pittsburgh, bought a sponsorship on NPR. I had heard the commercial before but hadn’t given it much credence. But now, sitting at a red light, I cocked my head in bemused thought. What if I learned how to code?

I posed that same question to Jenny when I met up with her and my daughter at my parents’ house.

“What if I learned how to code computers?” I asked.

It was an absurd suggestion.

She shrugged her shoulders. “Yeah. Do it.”

This excerpt from Refactored: My Attempt at Breaking into Tech During the Rise of the Coding Boot Camp is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reproduced without permission.