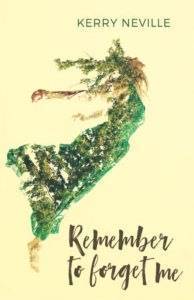

We’re so thrilled to be able to share this excerpt from Remember to Forget Me by Kerry Neville, which was recently published by Pittsburgh’s Braddock Avenue Books!

From the publisher: “With the publication of Remember to Forget Me comes the highly anticipated follow-up to Kerry Neville’s award-winning debut, Necessary Lies.

In this new volume, Neville peers with a steady eye into the universal struggle to lead a life of purpose and dignity. In ‘Zorya,’ we are drawn into the world of a former Ukrainian sex worker whose determination to embark on a new path with the dream of supporting her son and aging mother ends up subjecting her to even greater affronts. ‘Indignity’ takes us into the mind of a Polish widow who comes to the United States determined to start her life anew only to discover that her job as caregiver puts her into a painful collision with her past. In ‘Lionman’ (excerpted below), we witness a circus freak whose unexpected chance to satisfy his hunger for human connection leads to a nearly inconceivable revelation. And in the title story, a devoted husband thinks he has survived life’s final assault by consenting to have his beloved wife institutionalized for dementia—only to find that it’s just the beginning of his heartbreak.

With enormous compassion, Kerry Neville penetrates deep into the lives of people shattered as much by yearning as by loss. These are stories you won’t soon forget.”

“In these beautiful stories Kerry Neville moves effortlessly between young and old, Europe and America, always with passion, empathy and marvelous intelligence. Her vivid characters do not give up on love, despite distance, age and indignity. Remember to Forget Me is a wonderful and deeply rewarding collection.” —Margot Livesey, author of Mercury

From “The Lionman”

In the evening, Dreamland hummed under one million incandescent bulbs strung across its streets like tethered stars. Tens of thousands arrived by steamship from terminals in Manhattan and Harlem, jammed the promenades and exhibition halls, and jostled each other to see the corralled Wild Men of Borneo chanting their strange, guttural songs. Or Zip the What-Is-It Pinhead plucking haplessly at his banjo and hopping from foot to foot. Or the dwarves in Lilliputia in their scale model town of fifteenth-century Nuremburg with its own parliament, fire engine responding hourly to false alarms, and Chinese laundryman washing, ironing, and folding their small clothes into fastidious, warm stacks. Two hour lines for the Airships, the Ocean Wave, and the Giant Racer.

In the evening, Dreamland hummed under one million incandescent bulbs strung across its streets like tethered stars. Tens of thousands arrived by steamship from terminals in Manhattan and Harlem, jammed the promenades and exhibition halls, and jostled each other to see the corralled Wild Men of Borneo chanting their strange, guttural songs. Or Zip the What-Is-It Pinhead plucking haplessly at his banjo and hopping from foot to foot. Or the dwarves in Lilliputia in their scale model town of fifteenth-century Nuremburg with its own parliament, fire engine responding hourly to false alarms, and Chinese laundryman washing, ironing, and folding their small clothes into fastidious, warm stacks. Two hour lines for the Airships, the Ocean Wave, and the Giant Racer.

And they came to see him, the Lionman, tamed King of Beasts, reclining on a pile of turkey carpets. The brave and entitled demanded locks of his long, coarse mane as if they were talismans or trophies. He’d seen photos of rich men leaning on long rifles beside lion, rhino, and elephant carcasses, had been chased by poor men holding rocks, shouting epithets. A clipping seemed a small price for ease of mind. He backflipped three or four times in a row across the stage for a fist of coins, though more for the pleasure and rush of movement even though his knees and shoulders ached after a lifetime of acrobatics. One day, he’d miss and break his leg or crack his skull. Who would pay to see him then, hobbling on crutches, head wrapped like a mummy?

When the park emptied of the teeming crowds and fell quiet except for the odd roadster trundling down Surf Avenue, or the muted trumpets of Little Hip, the elephant, or the pickled laughter of other freaks staggering by (as much as it was possible to stagger with no legs or four), the Lionman stood at the window of the Baby Incubator, a mock farmhouse with timber beams and a gabled roof, better suited for Yorkshire than Brooklyn. Anchored at the peak, a stone stork hovered over a nest of cherubs; its beak pointed as if at a trough of herring. Inside the building, a row of premature infants in the incubators, boys pinned with blue ribbons, girls with pink. The heated boxes more peanut roasters than scientific wonders. Sometimes a nurse, the hefty one, eased an infant’s arm from the swaddling and slipped her diamond ring over the tiny fingers, then hand and wrist in an impromptu Tiffany bangle. Women tugged off their own rings, held them between their fingers, estimating the impossible measurement.

He pressed against the Incubator window, hair tickling his face like a woman’s lips, an approximate feeling as even prostitutes refused such intimacies, though allowed him, for fifty cents, to palm their pocked cheeks and trace the fine down from their temples to jaws. Afterwards, he stood at the sink, washing the tacky residue of face paint from his hands, and stared into the dim, spidered mirror, trying to see past his given lot. Dark eyes visible, but the planes of his face? A self obscured beneath hair, fur, coat, pelt? Time moving forward and through him, evidenced by the occasional silver strands plucked from his forehead and chin, but otherwise the same. He could only, always, look away.

Years before, the Lionman traveled in Baron Von Hausmann’s circus across the continent. The Baron was a tall, rickety man, his imperial mustache an autocratic punctuation. He locked him inside a small, rusty cage once home to a screeching monkey that served tea to a filthy doll; it died after drinking from a bucket of green paint. The Lionman, still a boy, was ordered to leap and growl at the bars, at little girls in particular, though they often giggled at his exaggerated, high-pitched ferocity. By evening, invariably tired and hungry, he slumped to the ground. The Baron whacked the bars with his cane, jabbing his ribs, startling him awake.

Once, he woke to a woman’s gloved finger stroking the long hair on his cheek. An exquisite tenderness, filled with pity and yearning. He shivered, mesmerized in sensation. She perched beside his cage, her black taffeta skirt collapsed around her in gleaming folds—a crow waiting clear-eyed on the tip of a branch. A toque cantilevered on top of a loose coil of hair. He held her steady blue eyes with his, waiting for her scream, for the chicken bone thrown from a pocket. This was what people did—shouted and threw scraps of food. In the countryside anyway, when the tents were set up in muddy fields ripe with horse shit. In the city, less food and more coins tossed through the bars.

The woman was close, her shallow inhalations and exhalations audible, and then so quick it might never have happened at all, her face against the rusty bars, fingertips beneath his chin, lips on his.

“Mein liebes kind,” she said, a whispered, sorrowful secret. An iron flake, a rusty petal, stuck to her creamy cheek; he imagined her whole face in bloom, tipped to the sun. Reach through the bars and brush it away? Disastrous. The Baron had beaten him for less.

Her hand rustled in her dress and reappeared, bills pinched between her fingers. She flicked them angrily and they scattered on the straw-covered ground. Had the strange yoking of sympathy and desire cost her too much? She rose, her back dismissing him. No matter. He had her money. Paper easier to hide than coins in the slit seam of his thin mattress. He lurched, snarling as she disappeared into the crowd.

The Incubator infants were swaddled in white blankets, wrapped tight against the shadows. So small and their need so great. Weeks and weeks early for this world. No defenses except the metal and glass boxes–what a magician might escape from in seconds–and Dr. Couney with his charts, droppers, and needles, and wet nurses whisking them to the nutrition parlor in back. Warm air, regulated by a thermostat, pumped through pipes across the bottoms of the incubators. Nothing more, really, than heated water chambers at a chick hatchery. The narrow mattresses rested on scales monitoring weight to the tenth of a gram. 970g, 1120g, 1460g: large numbers on cards attached to the boxes. Twice a day, the nurses switched them out, their faces flat and impassive as they took the readings. Spectators sneezed into grubby handkerchiefs, breathed their germy breath, and reached over the railing, leaving greasy fingerprints on the incubators’ windows. The nurses, in their spotless white dresses and peaked caps, strode through with rags and Lysol bottles, and rubbed at the glass in brisk, determined circles, then shoed back the crowds to wipe the railings.

The Lionman noted all this during his breaks each day and at night, when he was free to walk unmolested. He watched the nurse, the one with the soft eyes and hair that shimmered like the fields in Bavaria. That sun had fallen in benediction across wheat spreading out from the train tracks. His head had bumped a rhythm against the window. He imagined vaulting from the train like the Indian acrobats from their ladders, his wild mane, combed for fleas, lice, and chaff, disheveled from the flight and tumble. If he kept his bare palms and soles to the ground, he could disappear into all that rolling light.

Hildegard.

Violetta, the Half-Woman, told him her name. Dr. Couney called his daughter Hildy, and the two promenaded around the park in the evening like mismatched sweethearts. The doctor was always impeccable in dark broadcloth, spats, and a derby; he stooped, though, leaning on a crooked cane, and grasped onto his daughter’s arm as they walked past the exhibits, lingering at the entrances. He talked, gestured, and talked, perhaps agitated by the day’s events in the nursery; his daughter listened, nodded, and steered him through the crowd. In contrast to her father, Hildegard stood tall, her shoulders thrust back in youthful assurance and enthusiasm. It must have required great restraint to keep to her father’s measured pace; on her solitary walks, her feet moved quickly beneath her skirts, her arms switched back and forth, a purely constitutional outing.

The Lionman had been lying beside Violetta, a usual consideration to mitigate the distance between them since, like half a dress form, she had no arms or legs; of course, with her teeth, she sewed her armless dresses, lit cigarettes, and sketched spectators. And sang, not especially well, but with bravado—what it took when you looked like them. Sea shanties she learned from Ajax, the Sword Swallower: The Saucy Sailor Boy, Whiskey Johnny, and New York Girls. He propped his head with his hand; the kinky waves of his mane brushed the ground. He was still in costume: red Ottoman vest embroidered with gold flowers, blue, silk sash knotted at the waist, and black pantaloons.

“You’re like a pasha,” Violetta said, nudging him with her hip, a side shuffle she’d perfected. “You need a harem of those ticket girls.”

Those girls wore blue academic robes and mortarboards and stood in their booths, selling wheels of tickets each day. At night, as the lights flickered out across the park, the girls gathered at the entrance beside the massive, gold columns, then left in tight clusters for the train, glancing warily at the freaks ending their own long days in raucous, liquored companionship.

He smiled, lips closed over his nine teeth, all he ever had.

Violetta puffed her cigarette. “Imagine fucking one of them! And that girl, Couney’s daughter. You know, she was one of us, in one of those incubators. A regular miracle.” She spat the end of her cigarette to the ground where it glowed then winked out.

“We all are,” he said, “surviving them.” Them, the unmaimed who gawked and jeered, grabbed and punched and worse. When Violetta was a girl, a drunk carried her under his arm to an alley where he had his way, then left her with the garbage and rats, torn undergarments thrown, of course, she joked, just out of reach. Violetta recounted this one night as they talked of their time in the Chicago Exhibition, how he held her on his lap on the ferris wheel, the world’s first, as it rose up and down, carrying two thousand people around all the dazzling white buildings, the endless lake, and the distant city, how they saw the world stretch out before them. They boasted of the indignities they’d suffered, trading pain like the coin of the realm. Worse to be a Lionman or a Sealman? Nine feet or eighteen inches? Siamese twin or no limbs?

Excerpted from Remember to Forget Me by Kerry Neville. This excerpt should not be published without permission from the publisher.