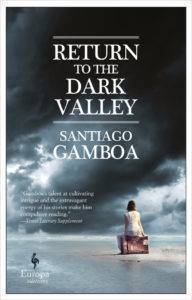

Santiago Gamboa is one of Colombia’s most prominent novelists, whose works combine a distinctly global literary sensibility with all the suspense and impact of great noir fiction. Gamboa lived abroad for many years, working as a diplomat and journalist in Rome, Paris, and New Delhi, among others, and only recently moved back to Colombia after 30 years of living abroad. He brings his international experience to bear in his novels, painting vibrant portraits of cities across the world and the people who inhabit them.

Don’t miss out: Gamboa will be visiting City of Asylum’s Alphabet City on Tuesday, September 19th to read from Return to the Dark Valley (published by Europa Editions, translated from the Spanish by Howard Curtis)!

From the Publisher: “Author Patricia Engel has called Gamboa ‘one of the greatest writers of our time,’ and in his new novel, Return to the Dark Valley, he is at the height of his literary powers, weaving an intricate polyphonic tale about exile and the impossibility of return, personal scars and the power of poetry. From Colombia to Madrid to Ethiopia, Gamboa’s characters are in constant movement, seeking to physically distance themselves from their dark, disturbing pasts and finding that their destinations are no more hospitable than the places they have left.

Santiago Gamboa is one of Colombia’s most exciting young writers. In the manner of Roberto Bolaño, Gamboa infuses his kaleidoscopic, cosmopolitan stories with a dose of inky dark noir that makes his novels intensely readable, his characters unforgettable, and his style influential.”

PART I

Theory of suffering bodies

(or Figures emerging from the wreckage)

These were still the difficult years. I was very tired and wanted to write a book about cheerful, silent, active people. That was my intention. I had spent time in India, about two years, and when I got back to Italy I found everything had changed. Sadness was everywhere now. An unexpected storm cloud hovered in the skies of Europe, and nothing was the way it had been. From the doors of the old Roman buildings hung overlapping “For Sale” notices, a kind of collage that dramatized the anguish of owners having to leave or at least to withstand the blows. The highways and byways of the city swarmed with people who hid their eyes or looked at each other with guilty expressions.

These were still the difficult years. I was very tired and wanted to write a book about cheerful, silent, active people. That was my intention. I had spent time in India, about two years, and when I got back to Italy I found everything had changed. Sadness was everywhere now. An unexpected storm cloud hovered in the skies of Europe, and nothing was the way it had been. From the doors of the old Roman buildings hung overlapping “For Sale” notices, a kind of collage that dramatized the anguish of owners having to leave or at least to withstand the blows. The highways and byways of the city swarmed with people who hid their eyes or looked at each other with guilty expressions.

Being there, just hanging about, with nothing specific to do on a working day, wasn’t the best letter of introduction. Nor did it demonstrate much social usefulness. Especially if you spent the hours in some corner café observing the transformation of the city and taking brief notes, making incoherent doodles, or drawing little men scaling mountains. That’s why it was best to change places frequently, in order not to attract attention and immediately be classified as a slacker or a piece of riffraff. When faced with a crisis, people are obsessed with respectability.

It’s understandable. When masses of people seek work without the least hope of finding it, when businesses reduce their personnel and the fashion stores announce sales out of season, the best thing to do is become a man without a face. The Invisible Man, the Man of the Crowd.

I was that man. Always observing, attentive to the slightest vibration, perhaps waiting for something, with a cup of tea or coffee in my hand, letting myself be swept along by the frantic activity of the passers-by, the way active humans come and go and fill squares and avenues, like shoals of fish driven by the tides. A movement that allows cities to go on living and produce wealth. To be healthy and respectable conurbations.

Exemplary conurbations.

This story begins the day my quiet life as an observer was shaken by a small earthquake. It was something very simple. I was sitting on a café terrace on Corso Trieste, watching the stream of pedestrians pass by in the direction of the African quarter, when my cell phone vibrated on the table.

A new message, I told myself. An e-mail.

“Please go to Madrid, Consul, to the Hotel de las Letras. Book into Room 711 and wait for me. Will be in touch. Juana.”

That was the whole message, not a word more. Enough to unleash a modest storm inside me, like galleries collapsing. Juana. That apparently harmless combination of letters that had occupied my life for a brief time. My mouth still open, uttering her name. It had all happened some years before.

I looked at my watch, it was eleven in the morning. I reread the message and felt an even greater sense of sadness, as if a current of air or a tornado were lifting me from my chair, above the avenue and its tall pines. I had to hurry. To run.

“I’ll be there today, await instructions,” I replied immediately, signaling to the waiter for my check.

Before long, I, too, was in movement, energetic and active, heading for the airport.

This excerpt of Return to the Dark Valley by Santiago Gamboa (translated from the Spanish by Howard Curtis) is published here courtesy of the author and the publisher, Europa Editions. It should not be reprinted without permission.