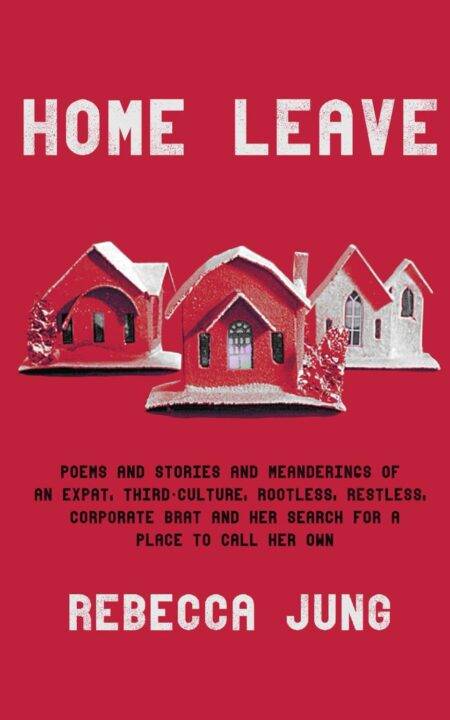

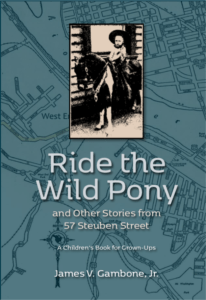

James V. Gambone Jr. (a Pittsburgh native) revisits the stories of his Polish grandmother — reportedly the city’s first female numbers bookie and moonshiner — in an entertaining new collection.

“Gambone’s vivid portrayal of his precious childhood relationship with his numbers-running grandmother, and his vignettes of life in a multi-ethnic poor neighborhood of Pittsburgh, deliver a touching picture that enriches our understanding of America.” —Gary Gilson, Emmy Award-winning documentary producer

From the Publisher: “Born into a Polish and Italian immigrant family, in a four-story tenement on Pittsburgh’s West End in 1945, James Gambone offers 14 entertaining stories from the city’s old-school underbelly. From his six-foot-tall, debt-collecting uncles ‘Rip’ and ‘Chill,’ to the daily numbers game that his Polish grandmother, Bessie Jarmac, ran out of their apartment, Gambone’s childhood was immersed in the city’s post-World War II, African-American, and new immigrant culture.

In Ride the Wild Pony (Elder Eye Press), Gambone recalls these events with striking detail, humor, and a familial love that shines on the page. Throughout these fourteen stories, the author as a very young boy “wins” a raffle for the first commercial Dumont TV by picking out his own ticket, learns to read Dream Books and recommend potential winning numbers to the neighborhood players, delivers betting slips on his tricycle past police to one of the numbers ‘runners,’ and helps his grandmother hide evidence during a police raid. All before the age of five! Ride the Wild Pony reveals a unique slice of Pittsburgh history in this ‘children’s book for grownups…'”

About the Author: James Gambone grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated from Duquesne University. He is an educator, award-winning film and television producer/director, and a nationally respected author/advocate on improving intergenerational relationships. Jim teaches in the School of Public Health at Capella University and co-owns a small multi-media consulting firm with his wife, Wendy Johnson.

Hurry and Get the Slips to Johnnie Heller!

If you grow up with a number’s bookie for a grandmother and an Italian “don” as a grandfather, you learn many things about your city and politics that pass by most young people. I think my lifelong interest in community issues traces directly back to this formative time in my life. Every day was a Civics lesson—but certainly not the Civics taught in school!

If you grow up with a number’s bookie for a grandmother and an Italian “don” as a grandfather, you learn many things about your city and politics that pass by most young people. I think my lifelong interest in community issues traces directly back to this formative time in my life. Every day was a Civics lesson—but certainly not the Civics taught in school!

In our house, the police were not our friends unless we gave them a cash envelope every few weeks. Politicians always demanded a piece of the action. When they didn’t get what they wanted, the small “entrepreneur,” like my grandmother, felt the heat. Citywide election years were always very tense times at 57 Steuben Street.

In normal times, Steuben Street had a beat cop who knew everyone and everything that was going on in the neighbourhood. This included knowing about Bessie’s small business. Bessie was always “very good” to the beat cop, and he occasionally played a number or two for free each week.

But during an election, everything changed dramatically. No matter how corrupt the incumbents were, they needed to look like they were tough on crime. The challenger always used the “numbers” as an example of the current administration’s ineffectiveness and corruption. The result was a series of surprise raids and arrests on known “criminal locations.” All of this made for good press but did nothing more than serve as an inconvenience to my grandmother.

Bessie was usually told in advance about these raids by the beat cop. When the cops and paddy wagon came, nobody would be in the house except Bessie. The kitchen table was clean, and there wasn’t a numbers slip to be found.

Bessie would still be arrested, politely asked to go downtown, but was immediately released after she was booked. I have always found it ironic that the police and Bessie were both in the “booking business.” A lawyer, who represented the Italian family that controlled the numbers on the West End, always posted her bail. Ironically, during my early college days, I worked for a law firm that defended one of the heads of the same family that oversaw Bessie’s operation. He claimed that he made his millions with great runs of “luck” at high stakes gin rummy in Florida!

But in 1950, things changed. There was a crackdown with an unusual twist. The story goes that the nationally organized Italian mob (the Mafia) wanted to eliminate powerful independents like the small independent family for which my grandmother worked. The national organization had bigger plans for Pittsburgh than just numbers. These plans included controlling loan sharking, drugs, sports betting, prostitution, and vending machines—just for starters.

Supported by unusually large campaign contributions, the “reformers” took on the local independent number’s operators. And when all of these political machinations translated down to the Steuben Street level, it meant Bessie was faced with a new set of rules for how to operate her “business.”

When the beat cop was removed, and strange people started appearing on the street, Bessie and her customers stopped playing for two or three days. I didn’t understand all of the politics, but I did understand that things were very tense. Since Bessie depended on her all night job of scrubbing the marble floors in the Mellon Bank downtown and her numbers business to make a living, a part of her livelihood was threatened. Still, she decided to continue despite the risks.

Routinely Bessie would gather up her numbers slips and the cash (minus her commission) in an envelope wrapped with a couple of thick gum bands. She would half-legibly write the total amount of cash for that day on the outside of the envelope and then tuck the envelope down between her large bosoms.

Bessie would walk five blocks up Steuben Street to the entrance of the “Pennsy” garage. The Pennsylvania Trucking garage had a long, dark driveway enclosed by tall brick walls on both sides that quickly turned off the street. There was a steep cobblestone grade leading down to a large steel garage door. The garage must have been used mostly at night since, during all the time I lived or walked on Steuben Street and later visited Bessie, I never saw the garage door open or a truck enter or leave.

It was at the bottom of this driveway entrance, near the large garage door, where Bessie would meet Johnnie Heller. Johnnie was a “runner” (someone who picked up the numbers slip from the bookie) for the Russo family.

Johnnie was a tall, gangly character with a front gold tooth that barely showed as he chomped down on a toothpick. That “pick” never seemed to leave the front of his mouth. He always wore a crumpled sports jacket, a colorful tie that never matched his jacket, and a fedora that would have made any gangster of the thirties proud.

Johnnie took his business very seriously. He never smiled and would always ask the same question: “Is it all there?” She would say, “Yes”—one of the few English words I ever heard her use, although I’m not sure she ever really understood Johnnie’s question. My grandma would then turn away from Johnnie, quickly reach down the front of her dress, and hand over the envelope. Johnnie would stay in the garage entrance until Bessie had turned the corner to go back on Steuben Street. Then he would walk away.

I made this trip with Bessie on a regular basis. I loved this time with my grandmother. Rain, snow, or shine, everybody on both sides of the street would yell a “Hello!” or “How are you, Bessie?” And after my incredible lucky streak, they would also say, “And how is that grandson of yours doing?” When we heard these things, I would beam with pride, and Bessie would gently tighten the grip on my little hand.

One particularly bad day during the “political crackdown,” somebody knocked on our door but didn’t come in. I could hear him whispering something to Bessie in Polish. Bessie told my mother, and they began speaking in Polish. My mother vigorously kept shaking her head, and Bessie seemed equally insistent. This went on for four or five minutes before my mother seemed to agree with my grandmother.

They both came over to me and said I would have something very special to do in a little while. I was excited because I always liked doing things with my mother and grandmother.

Bessie’s numbers business had been booming that morning despite the uneasiness on the street. I think tension sometimes makes people take more risks. When Bessie had put the last gum band around a rather thick envelope, she and my mother asked me to join them in the living room.

My mother brought my little tricycle out from the kitchen and asked me if I knew how to get up to the “Pennsy” garage. I knew this route and my grandma’s routine very well. There were no streets to cross, and I had even ridden my tricycle on this route for at least three of Bessie’s drops to Johnnie.

My mother explained that I would need to go up and give the slips to Johnnie by myself today. I thought this was really great. I was going to become an important part of the business. But even at the age of five, I had a vague understanding that this assignment had some element of danger.

Bessie tucked the envelope down the front of a bib-shorts outfit I was wearing. It caused a little bulge, but it wasn’t very noticeable. Then my mother and Bessie opened the door, got my bike down the short steps to the sidewalk, and said they would sit on the steps until I got back.

I began peddling as fast as my little feet could turn the pedals. People said, “Hi!” like they always did, but I was set on my purpose: Get the envelope to Johnnie Heller and get back to 57 Steuben Street!

About three blocks from the house, I peddled past a stranger going in the other direction. As I was low to the ground, I could easily see the gun and holster that his unbuttoned jacket hid from most peoples’ views. I kept peddling, and he paid no attention to me. When I reached the entrance to the garage, I was afraid for the first time. It was dark and shadowy at the end of the driveway, and I couldn’t see if Johnnie was there or not.

Almost simultaneously, I heard a sharp laugh and saw something very bright in the darkness. It was Johnnie’s bright gold tooth. “Jimmy, you stay there, and I’ll come up,” he said. I took the envelope out of my shorts and passed it to him without a hitch. He walked to the left, still laughing. I turned my bike around and headed back home. On the way, two uniformed cops who I didn’t know told me to slow down, or I might run somebody over. I slowed down. Mission accomplished.

This excerpt from Ride the Wild Pony is published here courtesy of the publisher and should not be reproduced without permission.