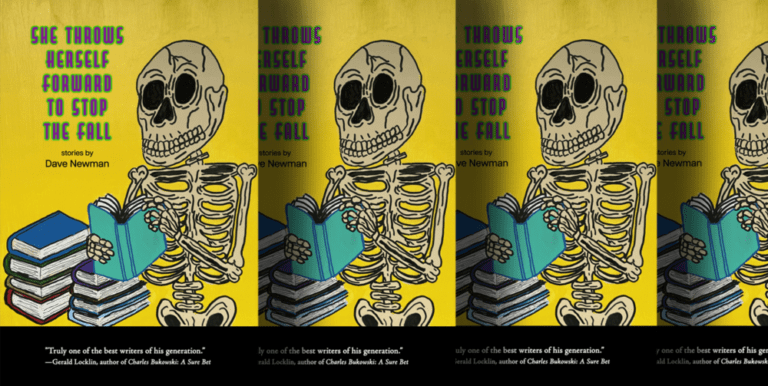

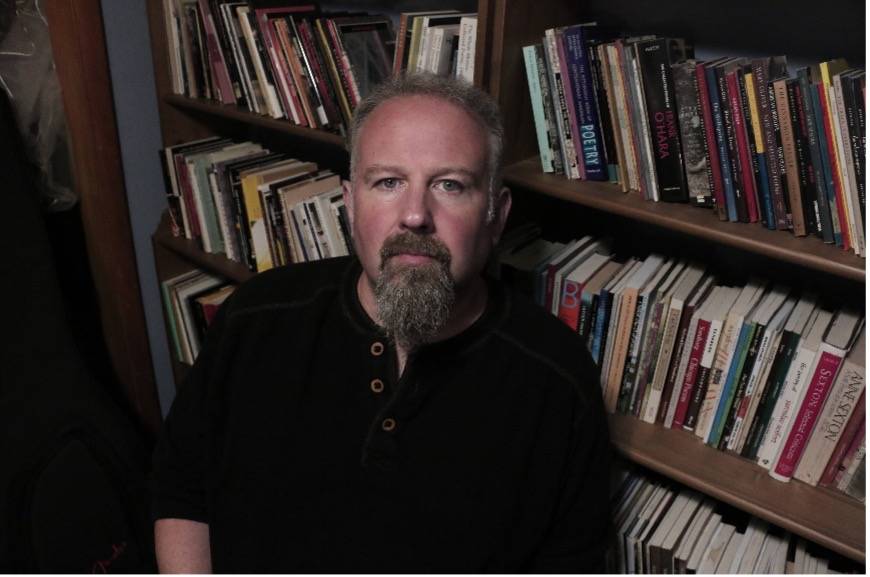

“Truly one of the best writers of his generation.”—Gerald Locklin, author of Charles Bukowski: A Sure Bet

New story collection by Dave Newman chronicles what happens when working-class people who can’t afford college go to college.

From the Publisher: “Pittsburgh author Dave Newman returns with She Throws Herself Forward to Stop the Fall (Roadside Press, August 2024), the final book in his trilogy about working-class people trying to better themselves through education.

In his critically acclaimed novel Raymond Carver Will Not Raise Our Children (Writers Tribe Books, 2012), Newman wrote from the perspective of a lowly lecturer on a one-year contract at a large university, desperately trying to hold onto his job.

In East Pittsburgh Downlow (J. New Books, 2019), Newman introduced Wade, a former welder turned community college professor trying to become a writer.

In his new story collection, She Throws Herself Forward to Stop the Fall, Newman delivers seven stories dealing with working-class people struggling through a bachelor’s degree at a branch campus outside of Pittsburgh. Adjunct professors struggle to pay their bills on terrible wages. Young students struggle to pay tuition. An assistant manager at a beauty store has been trying to graduate for nine years. A waitress has switched majors three times, can’t handle a full schedule of classes, and may never graduate. The struggles to get a degree are endless when you have a job that doesn’t care about your education.

A college-graduate makes a million more dollars over their lifetime than someone without a degree, but only if they can make it to class in a car that barely starts or pass a test they haven’t studied for because they picked up a double shift.

The stories in She Throws Herself Forward to Stop the Fall are quintessential American stories in a country where student-loan debt, rising tuition rates, the shuttering of universities, and the battle between quality and cost of a college education are constantly in the news.”

About the Book: “In She Throws Herself Forward to Stop the Fall, everyone is still in college, even though they are too old for college. The women in these stories work at the mall, work in bars, work in restaurants. They are middle-aged and live at home. They want to be writers. They want to be cops. Their boyfriends smoke crack and get lost. Their dads work in factories. Their grandfathers die without warning. Nothing is safe but everything will be fine. Go to class. Grab a cigarette. Pick up a broom. These are the stories of dreams and the endless work people do to survive.”

More info About the Author: Dave Newman is the author of eight books, including The Same Dead Songs: a memoir of working-class addictions (J.New Books, Spring 2023) and East Pittsburgh Downlow (J.New Books, 2019). His collection The Slaughterhouse Poems (White Gorilla Press, 2013) was named one of the best books of the year by L Magazine. His poems, essays, and stories have appeared in magazines around the world. He appeared in the PBS documentary narrated by Rick Sebak about Pittsburgh writers. Winner of numerous awards, including the Andre Dubus Novella Prize, he lives in Trafford, PA, the last town in the Electric Valley, with his wife, the writer Lori Jakiela, and their two children. After a decade of working in medical research, he currently teaches in the Creative and Professional Writing Program at The University of Pittsburgh-Greensburg.

Author Page About the Cover Artist: Lou Ickes is a Pittsburgh legend. An artist, musician, filmmaker, writer and more, he owns and operates Brillobox, Pittsburgh’s favorite outsider-artist bar. His independent film, The Search for Pittsburgh Bigfoot, is fast becoming a B-movie classic. Lou’s paintings can be seen in art spaces around Pittsburgh and at Brillobox, and his writing appears regularly in TINY DAY, a magazine that celebrates small lovely moments around Pittsburgh and San Francisco.

Artist Instagram Don’t miss out: The book release party for She Throws Herself Forward to Stop the Fall will be on August 22 at The Brillobox!

Event Info

Around three in the morning at Allegheny East in McKeesport, a branch campus of Allegheny University in Pittsburgh, Eric Poliski, who everyone called the goth kid, who thought of himself as the goth kid, who grew up in McKeesport with a crackhead father and a mother addicted to shopping, who swore he would move to New York someday after flipping off every person in Western Pennsylvania who said he was gay, which he was not, he just liked fashion, he came back to his dorm room and decided to kill himself.

It was February. The snow had melted then froze, making it hard to trudge across the parking lot in his leather Rick Barkum boots without slipping.

Back in his dorm Eric turned on his computer and moved the speakers to the floor. He put on Gracelandbecause, despite being goth, he loved Paul Simon. He took off his boots then his socks. He clipped his toenails. People worried about dying in clean underwear but it was your nails and hair they judged you by. Photos. Socials. He sat on his bed. The mattress was basically mush. He reached for the stereo and skipped to “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” his favorite song. He loved the melody, the way Paul Simon sang. He loved the lyrics and the story. The poor boy gets the rich girl and they both end up rich with diamonds on their shoes, theirs, not just hers. He thought that was what the song meant but maybe not. There were some African words at the beginning, some chants or a prayer, that he didn’t understand, so maybe the song was about something else.

Eric was flunking three of his five classes. He hated his professors. None of those fuckers were Paul Simon. His poetry teacher said he wasn’t allowed to write rhyming poems, like she knew shit, like she made the poetry rules and not the people with guitars who could actually fucking sing. She said, “Maybe read the books I assign and this will make more sense.” He said, “Maybe listen to Paul fucking Simon and my poems will make more sense,” and she walked away. His poetry professor was a twat.

He stood up and walked to the mirror.

He’d cut himself last year, not on his leg or the inside of his arm where no one could see, but across his face. He fingered the scar, wishing the line was bigger and deeper and more real. He’d used a razor blade and pressed lightly when he should have used something dull, like a screwdriver, like a corkscrew, and really forced the tip into his skin. The line above his eyebrow slashed down his forehead, skipped his eye, then started again on his cheek, but time and the sun had made it barely visible, more of a wrinkle than a scar.

He screamed at his face and walked back across the room.

If he could take the anger he put on everyone else and reflect it back on himself then he could end the anger forever. He knew this but not the means to make it so, except by killing himself, which seemed obvious yet necessary.

He tried to make a noose from his bed sheet but he couldn’t get the knot to slide. He was stoned on malt liquor and oxycontin. He loved oxycontin at least as much as Paul Simon. The first swigs of malt liquor always gagged him but the later sips warmed his tongue. He gave up on the bed sheet and decided to use his belt, a black leather strap with silver spikes. He made a loop and nailed the tail to his bed at a good height. He dropped the hammer. He loved hammers and nails, all kinds of tools, but he’d never learned to build anything. The fuckers back in shop class always called him a fag. He put his head through the loop and felt dizzy instantly, dizzy with all his air stuck inside him, which was what he wanted. He knelt down. He pulled with his throat. It went tight and he started to count the seconds.

At a party earlier in the evening, one he hadn’t been invited to, he said, “I’m miserable because I have to be around people like you,” to no one in particular. He said some version of that five or six or ten times, as many as it took to rile up the pleebs. The kids, mostly girls from the basketball team and a couple geeks from the sci-fi club, shouted him down then kicked him out when he wouldn’t leave. “We didn’t know he’d kill himself,” one girl said. “We just thought he was mean.”

The students on the newspaper thought about calling Eric emo as an inside joke but the editor wouldn’t allow it. The kid lived goth and he deserved to be remembered as goth. They could have just called him a creep. That was the consensus. He was a fake and a poseur and he’d masturbated with a noose. They’d never had a story like this. The editor called the police, both campus and state, and talked to various people and managed to get a copy of the report. They lifted some stuff from the Tribune Review and changed the wording so it wouldn’t be plagiarism. They kept interviewing students. A sophomore reporter who worked part-time in Admissions found the goth kid’s father’s name and number and the sports editor called but no one answered. Other people said his mom was in jail, busted for stealing ten grand in clothes from some designer store. They went online and found a woman in the Allegheny County Jail with the same last name. No one felt like calling the prison or knew if prisoners were allowed to get calls.

The goth kid would have been twenty in March. Twenty was too young to die but really, after twenty, life was seldom worth living. The goth kid’s roommate found him the next morning, still hanging, his feet turned bluish-black. He told the newspaper, “It didn’t surprise me. I mean, he didn’t like anyone. All he did was drink forties and that was it. And complain. He basically drank forties and complained. But he was a good dude, pretty much.”

The whole campus, when they weren’t joking about the goth kid who had hanged himself to Paul Simon, was pretty fucking sad.

Jana knew the goth kid a little.

She’d seen him at the Union, playing pool by himself. He wore headphones and sang like he didn’t know people could hear him singing to get attention. She thought he looked like a rapist. She thought he looked like a guy who’d punch you for not liking Kanye. She read the story in the newspaper and talked about it with a couple friends. She called it a tragedy to be polite and refused to make jokes or laugh at the jokes other people told, mostly to be nice but also because she was having a crisis of her own about money, about tuition, about the money she’d paid for tuition and how she couldn’t get it back.

After high school she’d worked full-time for thirty months straight to pay for college then started taking classes but still worked part-time, which was almost full-time, and her parents helped as best they could and she’d taken out student loans which she’d have to pay back whether she passed her classes or not.

A dead goth kid barely made a mark on the report card of her life.

Then, when Jana finally decided to do the right thing, when she came up with a plan and acted on it, her advisor said, “Honey, you can withdraw—basically, with the right forms—anytime you want to, but you can’t get your tuition back.”

Jana said, “What?” She said, “You’re kidding, right?”

She’d been meaning to drop her classes and now she’d missed the deadline. She was furious no one had told her about the deadline or that such a deadline existed. The people who ran the college were crazy. They lived on some planet where money didn’t matter, where people already knew what they needed to know about paying bills and refunds and deadlines but still attended college to learn about this shit.

Her advisor said, “Check your campus calendar, it’s there.”

Jana said, “Oh.”

The office was lime green, like the walls at Western Psych where Jana visited a friend who cut her wrists the wrong way to get attention back in high school. The desk here was metal with a fake wooden top. Plaques hung on the back wall saying this woman was qualified, that she held degrees, but Jana didn’t think so. She thought her advisor was more like the trash basket, cold and empty and industrial gray. On the corner of her desk was a framed list of all the things she’d learned in kindergarten and how those things would get her through life.

The advisor said, “It’s an honest mistake, honey.”

Jana was awkward with adults and she hated to stand up for herself. Her shoulders drooped and she tried to right her posture. She coughed but fake. She bottled and swirled all the furiousness around her stomach and head until she thought she would throw up in the advisor’s garbage can or across her desk.

Jana said, “I screwed up,” pretending to accept the blame.

She made a sad face, which felt more comfortable than an angry face, and she hoped the advisor might see her sad face and be moved to act on it.

The advisor, an older woman, maybe fifty, fat, big-haired, wearing a sweater covered in lint balls, sighed and made her own face, a happy face, or maybe a sympathetic sad face, or maybe she looked bored. The fatness made her features hard to read.

Jana said, “I didn’t know what I was doing.”

The advisor said, “It’s a learning experience. That’s what college is about. If we don’t fall, we never learn to get back up.”

Jana said, “But this costs money.”

The advisor said, “Yup, it does.”

Jana said, “Oh.”

Jana said, “Yeah, but—”

Jana said, “That’s a really expensive way to fall.”

The advisor said, “It really is,” and opened a drawer and dropped in a form.

Halfway across campus, without a cigarette, craving, approaching an anxiety attack like she hadn’t had since high school, her tongue dry as cafeteria bread, starting to shake, her lower back soaked in sweat despite the cold and the wind, Jana remembered the goth kid and how he’d killed himself to Paul Simon.

She thought: what about that loser’s tuition?

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.