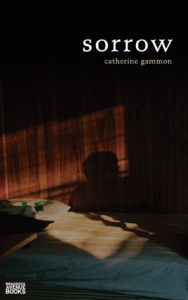

Catherine Gammon is a fiction writer and Soto Zen priest who has recently returned to Pittsburgh. Her novel Sorrow, published by Pittsburgh’s Braddock Avenue Books in 2013, was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award. Her novel Isabel Out of the Rain was published in 1991 by Mercury House, and her shorter fiction has appeared in literary journals for many years. She served on the faculty of the Master of Fine Arts program of the University of Pittsburgh before leaving the university to begin formal Zen training.

Gammon’s work has received support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the American Antiquarian Society, among others, and from colonies including the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Yaddo, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Djerassi. Her fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, Agni, Iowa Review, North American Review, Manoa, Missouri Review, Kenyon Review, Other Voices, and The Collagist, among others. A current novel excerpt appears in New England Review, along with an online “Beyond the Byline” interview.

Gammon trained for twelve years in residence at San Francisco Zen Center, where in 2005 she was ordained a priest in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi by Tenshin Reb Anderson Roshi. Since serving as Shuso in 2010 at SFZC’s Green Dragon Temple/Green Gulch Farm, she has given teachings in Zen and writing in the U.K., in Brooklyn, in Pittsburgh, in Massachusetts, and at Green Gulch Farm. In 2017 she returned to live full time in Pittsburgh, and she frequently offers her Zen-based writing retreat, Writing As A Wisdom Project, here.

Read two excerpts from Gammon’s novel Sorrow below…

Praise for Catherine Gammon:

“Sorrow is a devastating, gorgeous, impossible, unstoppable book–powered by unbearable desire, murder, a stunning turbulence of language and story. The real triumphs of this novel are Anita, Magda, Danny, Tomás, Cruz, people you will never forget even though tragedy, abuse, and circumstance did their best to render them invisible. A tour de force.”

– Eve Ensler, author of The Vagina Monologues and In the Body of the World

Catherine Gammon is that rarest of entities, a gifted prose stylist with vision and high moral purpose. Her work is intense, penetrating, and about as ephemeral as the Himalayas. Brilliant is a term at risk of fading from overuse; we must all be careful not to devalue it any further by declaring a new writer of brilliance every other week. With that in mind, I hereby spend one of my extremely limited stock. Gammon is a brilliant writer, and an important one.

— Michael Cunningham

On the street Anita ran into Tomás, coming home from stocking supermarket shelves. His English had somewhat improved and he was able to tell her that he was surprised to see her out so late, but pleased, and would she have a coffee with him? What he could not tell her was what his cousin Cruz had warned him about her, that sometimes this would happen, he would meet her in the street, wild-eyed like this, with streaming hair and her breasts free, the nipples showing hard through her T-shirt. What he had not told his cousin was that this would please him, not only for the reasons Cruz would imagine and condemn, but also because to see her like that would remind him of the girlfriend he had left back in San Salvador, a girl from the university who loved him a little perhaps but not enough, a girl who loved guerrillas more, and if not them, then at least musicians who wore their hair long like yanqui rock-and-roll stars from the days when all the young people in El Norte wanted to look like Che Guevara and made him a saint, a Christ when he was killed with bullets, the photos of his body a pietà and the whole of the Americas a place of holy war. What she had wanted was to be like those girls then, those California gringas, with their long hair streaming and no bra or underpants or shoes, those girls who slept with anyone they felt like and enjoyed it and felt no shame for anything, no guilt to the church or to men, to their mothers or fathers or brothers, no guilt to the men or boys who loved them, the men or boys they betrayed. No guilt like men, she had said to him, laughing. When he saw Anita like this she reminded him of that girl, a girl he had been unable to keep because he had not been a guerrillero, was not even political, was not a musician, because he did not wear his hair long and didn’t like it that she had sex with other men—because he was not even sure he liked it that she had sex with him. If she refused to feel guilty, he would carry the guilt for both. Despite what he thought were her wild ways, she was innocent at heart. They made love to each other like children. Each time, he thought, like children. He touched her in wonder. Each time he touched her she cried. As if she had never been touched before. It moved him that she cried. He thought it was love. Anita excited this feeling in him too. Something tender and desiring, all at once. Her name was Barbara. After the saint, he had thought, until she told him no, her mother was a fan of Barbara Stanwyck, the gringa actress. It was a family with plenty of money. Not rich, but plenty. They didn’t care about their daughter, Tomás thought. They didn’t try to control her or make her change her ways. Her father had worked for yanquis too long. She wanted to sabotage her father, Barbara told him. She was always plotting, but had no idea how to carry out her plots. She was a romantic, Tomás thought. A foolish girl. She had taken up with him because of his working-class background. She thought he would lead her into something deeper than his family’s poverty and his own hard work to escape it. It was his brother that she loved, maybe, even though she’d never met him, his brother the compañero, his father the martyr. Tomás himself she could hardly see. Except those times in bed, when he touched her and she cried, when he let himself go inside her and she came. My panther, she called him. My wild animal. And Tomás was pleased.

On the street Anita ran into Tomás, coming home from stocking supermarket shelves. His English had somewhat improved and he was able to tell her that he was surprised to see her out so late, but pleased, and would she have a coffee with him? What he could not tell her was what his cousin Cruz had warned him about her, that sometimes this would happen, he would meet her in the street, wild-eyed like this, with streaming hair and her breasts free, the nipples showing hard through her T-shirt. What he had not told his cousin was that this would please him, not only for the reasons Cruz would imagine and condemn, but also because to see her like that would remind him of the girlfriend he had left back in San Salvador, a girl from the university who loved him a little perhaps but not enough, a girl who loved guerrillas more, and if not them, then at least musicians who wore their hair long like yanqui rock-and-roll stars from the days when all the young people in El Norte wanted to look like Che Guevara and made him a saint, a Christ when he was killed with bullets, the photos of his body a pietà and the whole of the Americas a place of holy war. What she had wanted was to be like those girls then, those California gringas, with their long hair streaming and no bra or underpants or shoes, those girls who slept with anyone they felt like and enjoyed it and felt no shame for anything, no guilt to the church or to men, to their mothers or fathers or brothers, no guilt to the men or boys who loved them, the men or boys they betrayed. No guilt like men, she had said to him, laughing. When he saw Anita like this she reminded him of that girl, a girl he had been unable to keep because he had not been a guerrillero, was not even political, was not a musician, because he did not wear his hair long and didn’t like it that she had sex with other men—because he was not even sure he liked it that she had sex with him. If she refused to feel guilty, he would carry the guilt for both. Despite what he thought were her wild ways, she was innocent at heart. They made love to each other like children. Each time, he thought, like children. He touched her in wonder. Each time he touched her she cried. As if she had never been touched before. It moved him that she cried. He thought it was love. Anita excited this feeling in him too. Something tender and desiring, all at once. Her name was Barbara. After the saint, he had thought, until she told him no, her mother was a fan of Barbara Stanwyck, the gringa actress. It was a family with plenty of money. Not rich, but plenty. They didn’t care about their daughter, Tomás thought. They didn’t try to control her or make her change her ways. Her father had worked for yanquis too long. She wanted to sabotage her father, Barbara told him. She was always plotting, but had no idea how to carry out her plots. She was a romantic, Tomás thought. A foolish girl. She had taken up with him because of his working-class background. She thought he would lead her into something deeper than his family’s poverty and his own hard work to escape it. It was his brother that she loved, maybe, even though she’d never met him, his brother the compañero, his father the martyr. Tomás himself she could hardly see. Except those times in bed, when he touched her and she cried, when he let himself go inside her and she came. My panther, she called him. My wild animal. And Tomás was pleased.

He sat now in the bright artificial light of an all-night pizza stand drinking coffee that was thin and old out of a paper cup, across the white, unnatural tabletop from another wild-eyed, wild-haired girl. She was strange he thought, usually so proper and shy, and now like this—still shy, but so changed: in the way she held her body, in the way her eyes met his and didn’t look down or off to the side, in the trace of a smile that played at her mouth, in her mouth itself—almost the mouth of a different girl, usually drawn, tight, but now so full and open—as if any minute she might kiss him, as if all the while they sat together she was inviting him to kiss her, inviting more than kisses . . . The thought disturbed him, became too physical. He looked away from her. He wished he could speak more English, to tell her what was in his heart. He didn’t like that their conversation was of necessity so silent, so much in the body.

She reached for his hand.

She was startled to see the sadness in his eyes, and looked down suddenly, at her own hand resting on his, and pulled her hand back, clenching it tightly to herself—both hands making little fists, the nails cutting into her palms, the muscles in her arms tense as she held them close to her body, wrists crossed. She looked up at him again and felt her whole self withdraw, condense. Outside, the night sky was beginning to lighten, dawn was almost coming up. An old man with rat whiskers and a janitor’s broom was the only other person in this place except for the two guys behind the counter, who hung out at the pizza ovens smoking, talking in Arabic—or Pashto or Farsi or Urdu, Hindi maybe, or Turkish, Armenian, Greek. She understood only their laughter. The younger man met her eyes. He would have been the one, she thought. He was tall, almost handsome. His hair was long. His tongue came out of his mouth to lick his upper lip as he smiled. Even as she sat here with Tomás, this man smiled at her that way and spoke to his friend and laughed. She imagined herself with him, in the back maybe, where they piled bags of trash, or underground against cardboard boxes filled with soda cans and cans of pizza sauce and mushrooms and peppers—naked on a bed of empties, and the old man with the broom somewhere, whistling.

She turned back to Tomás. What she wanted now was flight.

When Tomás came down from Anita’s, he found his cousin waiting for him at the little living room table where they generally ate breakfast, where now he saw a letter from his mother among the bills and advertisements lying there. He didn’t want to talk to Cruz but saw that he couldn’t avoid it. He sat at the table and reached for the letter.

“The policeman was here again,” Cruz said.

“Yes,” Tomás said. “I saw him.”

“How is she?”

Tomás shrugged. He didn’t know what to tell him, how much to say.

“He thinks Anita killed her mother,” Cruz said.

“I think so, yes,” Tomás said. He opened his mother’s letter and began to read. A priest had written it for her—a priest she could trust, she told him. She had received a message from Guillermo. He was alive in Morazán province. He had sent someone to speak to her, to tell her that he was alive, that he had hope now for the war to end, that he had hope for peace, for a new world, hope that he would be reunited with her and with his brothers and sisters. The negotiations were proceeding, he told her. The reports were true. It was possible that the war would end. We will not have won all that we have wanted, he said, but we will have won enough to rest, enough to build a new future, enough to work in peace for justice and freedom. There was still danger, but he had hope. His mother was also full of hope, but lonely. She begged Tomás to come home.

Tomás glanced up at Cruz, who was watching him expectantly. He held the letter out, but Cruz kept his eyes on him.

Tomás blushed.

“Do you love her?” Cruz asked.

Tomás looked at the letter in his hand, the letter from his mother, Cruz’s aunt, who had worked and played in the coffee-growing country with his cousin when they both were children, when their families had not yet moved to the city to look for better work and freedom, as Cruz had come twenty-five years ago to New York, as Tomás had come now: the little letter seemed suddenly to hold it all—the terror and the fate of their country, so full of hope and sadness and love. “Do you love her?” Cruz had asked him about Anita, and maybe it was true, but for a moment Tomás had thought Cruz meant his mother and Salvador itself. He remembered Anita in his arms, and felt her still all over his skin. He remembered how she had spoken to him, taunted him, how she had acted like a whore to him and maybe even told him that yes, she had killed her mother, although he wasn’t sure. He remembered how he had hit her to make her stop, and how she had stopped. He was ashamed.

“I can’t tell you,” he said to Cruz. “It is between Anita and me.”

“But you will treat her with justice, with love?” Cruz said.

“With love and justice,” Tomás repeated. He studied his cousin and didn’t know what more to say.

“You will protect her,” Cruz said, “from the policeman.”

Tomás hesitated. He tried to describe for him what he had observed when the policeman was with her, then interrupted himself. “I didn’t understand him,” he said. “I didn’t understand all that he said to her.” This was true, but not the reason he stopped talking. He had caught himself thinking that Anita might really be guilty and he did not want to convey this thought to his cousin, or even to convey to him the exchange between Anita and Sydney Booker, the memory of which had awakened in him the thought of her possible guilt. It would be best if Cruz continued to believe Anita was innocent. For himself, he wasn’t sure: not sure what to believe, what it would be best to believe, or what he felt either. He knew he desired her, more fiercely now than he had before. He knew now that she had a hold on him that touched him very deeply, not only in his desire for her and in his feelings for her body but also in his heart, in his compassion for her suffering, for the lost way she had about her and the anger that came out of her and the pain in all her whore talk and her angry offering of herself that was not the offer of love but of killing, erasure. Yes, he thought, she could have killed her mother, and even that thought increased his passion for her, along with his desire. She was an animal and a child and a lost and confused living creature and a beautiful woman and her tears against his chest were something old, ancient; they touched something ancient and old in him that didn’t care about her mother or Cruz or the policeman or his brother in Morazán or his country or peace or war or maybe not even his own life or death.

Was that love? he wondered. Was that what Cruz meant when he asked him did he love her? It seemed more than love, or less. Too hard for love, too animal—and too old, reaching back to original time, as if he had known her forever. Was this what love was? The love he saw around him, the love in songs and movies and on greeting cards and on TV—could it be this?

Copyright © Catherine Gammon. This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.