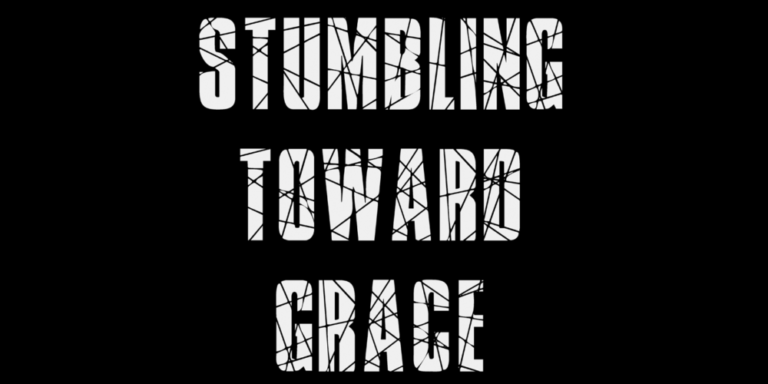

“Rosalia Scalia is Baltimore’s Flannery O’Connor. She inhabits her disparate characters, warts and all. Not an easy task considering the bigots, religious fanatics, hoarders, alcoholics, drug users, and damaged lives presented here. And yet, like the fictional Father Brown, she refrains from judgments, allowing each a generous shot at redemption.” –Richard Peabody, editor/publisher, Gargoyle Magazine

From the Publisher: “Sometimes we try to connect to others, especially people we love but end up missing each other for a variety of reasons.

The stories in Stumbling Toward Grace explore instances of imperfect people trying to connect to loved ones and others despite fractured relationships and personal flaws. These are ordinary people striving to survive and thrive in situations reflective of today’s challenges.

A wife can no longer deal with her husband’s recent paralysis.

A husband desperately wants his wife to reconsider separating.

A terminally ill man seeks to reconnect with his estranged daughter after cutting ties over an interracial marriage.

A freelancing nun attempts to “save” a single mother from the perils of society.

Rosalia Scalia vigorously examines people at their best and their worst. We are invited to witness how people who love each other struggle to reconnect their fractured relationships in the face of traumas, personal flaws, and unspoken hurts. Stumbling Toward Grace combines loss and grief with humor and grace as characters navigate their unwise decisions, unexpected deaths, or their resentments polished into gems.”

More info About the Author: Rosalia Scalia‘s fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in The Oklahoma Review, North Atlantic Review, Notre Dame Review, The Portland Review, and Quercus Review, among many others. She holds an MA in writing from Johns Hopkins University and is a Maryland State Arts Council Independent Artist’s Award recipient. She won the Editor’s Select award from Willow Review and her short story in Pebble Lake was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She lives in Baltimore with her family.

Author Site

An Excerpt from “Picking Cicoria” from the short story collection Stumbling Toward Grace by Rosalia Scalia

The last place Connie Sessa wanted to be was sitting in the passenger seat of her father’s Dodge Dart, an old vehicle with a faded green finish, a missing muffler, and dents from his bumper car driving style. The engine coughed and sputtered before it turned over, and when it finally rumbled to life, shattering the Sunday morning silence with its roar, he shifted into gear and pulled away.

The last place Connie Sessa wanted to be was sitting in the passenger seat of her father’s Dodge Dart, an old vehicle with a faded green finish, a missing muffler, and dents from his bumper car driving style. The engine coughed and sputtered before it turned over, and when it finally rumbled to life, shattering the Sunday morning silence with its roar, he shifted into gear and pulled away.

Through the window, Connie glared at her mother. Still in her nightgown, with her graying curly hair tied in a loose ponytail, her mother smiled and waved from the front window of their Little Italy row house.

“Fai attenzione. Pay attention,” her mother had said as she handed Connie, who was thirteen years old, two large kitchen knives wrapped in butcher paper and three folded brown supermarket bags, which the girl tucked into the car’s glove compartment. Cross and sleepy, Connie hadn’t wanted to fai attenzione.

She watched a dozen gray and white pigeons strut around a pile of bread crumbs. As they pecked at the crumbs, their necks jutted in and out. She wondered if she would able to get close enough to put salt on their tails, would they be able to fly? Her father had told her that salt disables their wings. She spent countless hours as a child, with a salt shaker in hand, chasing starlings and pigeons and trying to get close enough to sprinkle salt on their tails. Seagulls competed for the crumb pile. Their huge wings swooshed away the pigeons flapping as they rose and fell away from the pile.

The sun, barely risen over the rooftops of Baltimore’s soldier-like homes, cast a gold sheen on the car’s torn green seats. The church’s bells had not yet tolled their melodic summons to the morning Mass.

Connie yawned, wondering what would actually happen next time if she refused to go foraging with her father on Sunday mornings. She much preferred sleeping for another hour or playing with her furry black cat before having to put on a lacy Sunday dresses for church, than picking cicoria or chicory. She had put on her worst clothes-jeans with holes in the knees, ripped tennis shoes, and an old, worn T-shirt so to not ruin her good ones. She set her head on the window and shut her eyes.

“Ready? You no looka ready,” her father, smoothing his cap, said. “Waka up.”

Embarrassed and annoyed, she frowned at his black knee-high socks on his sandaled feet. She wished he would dress as if he’d been here since he was twenty, she thought. It was the ’70s already. He could at least lose the black knee-highs when he wore sandals and wear regular shorts instead of those baggy things he called “halfa-pants.” Her father pointed the car toward Lombard Street, away from the rising sun, and pressed his socked-and-sandaled toes on the gas.

She prayed no one would be at the Fort to notice them—especially not Tony Cardoni, who made her heart beat faster than her grandfather’s sewing machine. Not her cousin Rosa or her Uncle Joe, who was her father’s brother. They had the same bad taste in fashion that made them look like matching bookends. And especially not anyone from her school, the normal people who’d go to the Fort to explore its history instead of its foliage. With her whole heart, she wished she could transport herself out of the car.

Her father’s rotund body barely squeezed into his plaid shorts, and a white tank undershirt revealed rolls of fat around his shoulders and back. His cap hid the ever-widening bald spot on the top of his head, and a big mustache, looking like a tarantula hanging above his lip, gave him the appearance of a pudgy bandit on vacation.

She hadn’t been the only one to think so either. The salesman at a jewelry store must have fingered him for a bandit too. Why else would the man glare at them, follow them around the shop, and watch their every move when Pop had taken her and her sisters there to get a present for their mother’s birthday? The man looked surprised when her father paid for a pair of diamond and pearl earrings with a wad of cash.

Although he’d been in America long before Connie was born, to her, he still looked and acted as if he was fresh from the “old country” as he called it. Some things just don’t change, regardless of the geography. Just like back atop a mountainside in Sicily, the same routine dominated Sundays: pick cicoria, go to church, and eat dinner at noon. In Baltimore, the cicoria picking season started in May and ended in August. The only thing that changed every Sunday was the place.

Last Sunday, they had gone to the Greenmount Avenue cemetery, an expansive place in the middle of the city and where the most famous Baltimoreans were buried, to pick the stalks with purple-blue flowers. They had spotted heartthrob Tony, his mother, and his elderly aunt there, already bent over the stalks growing up along the graveyard’s section boundaries. They had been cutting away at them like migrant workers, earning pennies per pound. Tony’s aunt had twisted the skirt of her dress into a knot so that it formed a makeshift basket. Knife in hand and stooped over the plants, she cut the stalks and dumped them into her dress.

Connie’s face had flushed when Tony had spotted her. She’d imagined running into Tony in a million different places but not while picking cicoria. She turned her face, red from embarrassment, away from him, who also looked mortified as if he wanted to shrink to the size of a gnat. She had understood perfectly. She had raised her knife a bit higher before she brought it down on a clump of cicoria and winked at him. She rolled her eyes toward her father.

Tony had raised his eyebrows at her in return and pointed his chin at his mother and sister. She got it: neither of them wanted to be there, and neither of them had a choice about it. He’d smiled, and her heart had thumped. She was certain that Tony, like herself, had probably visited a myriad of places where wild grasses grew on the quest for cicoria against his wishes.

She and her father had visited cemeteries, parks, hospitals, college campuses, elementary and high school grounds, and other places that he’d heard about through the mysterious network that also sent other foragers to the same places. Each week, they had seen the same faces at the various sites, each competing for the ever-dwindling stalks. Then her mother had heard a whisper about the Fort, supposedly filled with cicoria in spots that dogs couldn’t easily reach—and as yet unexploited by the regular foragers.

Turning the car onto Fort Avenue, her father drove straight toward the fort. This morning, they were pioneering new territory that was safe from dog walkers and their ruinous peeing dogs. Connie could list about a hundred things she preferred to do, and at least Tony wouldn’t be there. She sighed. She dreaded new territories; they always made her nervous about running into her friends and their parents doing normal things like walking around and not picking cicoria.

Not foraging for food.

“Maybe we finda some good stuff today,” her father said.

Connie shrugged, not caring about the quality of the plants today. She clicked the button to the glove compartment to and fro and yawned.

“Stoppa dat noise!” her father snapped.

‘Tm not doing this next Sunday,” she said, crossing her arms. “You donta tell me whata gonna do. I tella you, and I’ma tella you next Sunday, we picking cicoria.”

She promised herself this day would be her last Sunday foraging for stupid greens.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.