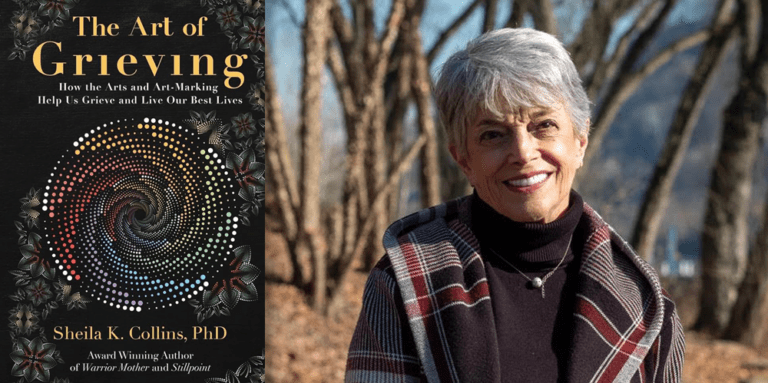

From the Publisher: “Author and Therapist Sheila K. Collins invites readers to embrace grief as an art form in her upcoming book, The Art of Grieving. In this poignant and insightful work, Collins challenges the conventional view of grief as a transient emotion, proposing instead that it be approached as a skill to be cultivated and mastered throughout life. Collins knows grief first-hand, having lost her son to AIDS-related illness and her daughter to breast cancer.

Drawing from her extensive background as a dancer, social worker, mother, and author, Collins explores the transformative power of art in the grieving process. Through dance, storytelling, and other creative mediums, she offers readers practical tools to navigate the complex terrain of loss with grace and resilience.

‘In the art of living our life, loss is a frequent episodic occurrence expected to happen throughout our years,’ says Collins. ‘Grieving needs to be an art we practice and eventually get good at.’

With compassion and wisdom, Collins guides readers through the stages of grief, providing inspiration and encouragement for those navigating their journey of loss, whether recent or long ago. She emphasizes the importance of acknowledging and processing grief, especially in the face of mounting communal losses that affect us all.

‘Good happens and bad happens, and just like food, we need to process it,’ explains Collins. ‘Wisdom comes from processing grief, and the aim is to make grieving acceptable and something we can welcome, as there is so much richness in staying attached to our past.’

As a grief advocate, Collins is dedicated to helping individuals find healing and meaning in their experiences of loss. Through The Art of Grieving, she invites readers to embrace grief as an integral part of the human experience, offering solace and support in times of sorrow.

For those seeking guidance in navigating their grief journey or supporting others through loss, The Art of Grieving promises to be a valuable resource and companion.”

More info About the Author: Sheila K. Collins is a dancer, social worker, and author dedicated to exploring the intersection of art and healing. With over three decades of experience in the field, she has helped countless individuals find solace and transformation through creative expression. Collins is the author of several books, including Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and Rituals that Heal and Stillpoint: A Selfcare Playbook for Caregivers to Find Ease, Time to Breathe and Reclaim Joy. Sheila is a licensed therapist with degrees from Monteith College, Wayne State University, and the University of Nebraska. She and her partner, Richard, call Pittsburgh, PA home.

Author Site Don’t miss out: The official release of The Art of Grieving is May 14, 2024, with an in-person launch party set for 7 pm, May 16, 2024, at the Jewish Community Center at 5738 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15217.

“How many children do you have?”

It was the question I dreaded the most—the question that would come up early on in nearly every conversation I had when my husband and I moved from Fort Worth, Texas, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 2005. What made this simple “getting to know you” question so difficult was that just nine months before these conversations, our forty-two-year-old daughter, Corinne, had died of breast cancer. Then, there were other details in my biography. Seven years before Corinne’s death, our son Kenneth died of AIDS after a four-year journey with that disease, just after his thirty-first birthday. When I was able to somehow get through my discomfort to communicate these facts, not just distract from the question by talking about my other son Kevin and my granddaughter Kyra living in California, the person who asked the question would say, with an embarrassed or shocked look on their face, “Oh, I am so sorry.”

Some people would then back away, create more space between us, and look around the room, searching for a way to exit the space gracefully. If the person could stay in the conversation, our next exchanges were attempts by both of us to alleviate the cloud of discomfort rising between us. I would try to recover from the fact that I had not presented the information well and begin reassuring the person that it wasn’t all as bad as it sounded. They would tell me some version of how “I could never handle things as well as you seem to be handling them” or “I could never survive the death of a child, and you have lost two.”

And me? I was left feeling isolated, like a pariah, someone to be avoided, as though what had happened to me in my life might be contagious.

Loss is common; it’s inevitable; we can count on experiencing many episodes of loss in a lifetime, often coming when we least expect them if we hadn’t known that before March,2020 and the big global shutdown, we surely know it now. However, by 2022, in an editor’s response to an early version of a proposal for this book, I was told that publishers were not interested in anything related to the pandemic. By the time the book would be published, people would be ready to move on.

But it is impossible to move on fully. If we can pause a moment to reflect on lessons learned as we emerge from the isolation and fear for our lives and our health that the pandemic inflicted on us, we see that death is not all we need to grieve. We grieve many types of loss, many of which the pandemic illuminated. There’s the loss of normalcy, of the familiar, of what we expected to do in this period and time of our lives. The loss of what we counted on: jobs, paychecks, attending sporting events and theaters, socializing in groups of friends, and being able to travel freely. And let’s take a pause to acknowledge some of the people, places, and activities we have loved that are not coming back.

These same types of losses have impacted people differently due to multiple factors, such as availability of resources, timing in our life cycles, and temperament. Each loss and our grieving for it changes us and our lives in both expected and unexpected ways. Since grieving is how we process our losses, I am convinced of its importance. Since losses will continue to happen, grieving is a necessary set of skills—an art we need to get good at to have a satisfying life.

My story of awkward exchanges in meeting new people after the death of my two children is most likely not unfamiliar to you. In the “get over it” swagger that passes for a successful life skill, mourners are often left in social isolation to “fake it till we make it,” being careful not to disturb other people’s attempts to do the same. As I attempted to grieve and process my losses, I confronted how much I didn’t know about grieving or about supporting others through their grief as I was going through mine. This seemed more than a bit odd, my having had a thirty-year career as a mental health professional. I was not taught, nor were other mental health professionals of my generation taught, the answers to the questions raised by my own life experiences. Even though I’d taught and mentored emerging helping professionals, accompanying hundreds of clients on their journeys through grief and loss, there was still so much I didn’t understand about grief and the grieving process, especially our culture’s discomfort with it. I began looking for answers to the following questions and will be exploring those answers with you in this book:

-

- How did we get grief so wrong in our Western culture?

- What does healthy grieving look like?

- What helps and what hinders the grieving process?

- How can we become more comfortable supporting family members, friends, and neighbors who are going through it?

- How should we relate to the sorrows of the world that technology brings into our living rooms and onto our handheld devices most days?

- My own experiences showed me that grief has some gifts, and I wondered: Why didn’t I know about them? Shouldn’t we all know about them?

As a teacher and therapist accustomed to giving homework assignments to students and clients, I decided to give myself a homework assignment. It began with imagining: “What if we assume, in the art of living a life, that loss is a frequent, episodic occurrence, expected to happen throughout our years, and that grieving needs to be an art we practice and eventually get good at?” Next, I wondered, “Is it possible that many of our societal troubles occur because we don’t know how to grieve well?” Perhaps grieving is made more difficult because communal grieving processes are not in place to help individuals and communities grieve losses when they happen, especially losses due to large-scale societal forces. And then, as a dancer and improvisational performer, I wondered, “Could the arts be tools to express our hopes and sorrows while offering ways to memorialize and celebrate those that have gone before us, much like what happened for our ancestors, and still does in many of the world’s indigenous cultures?”

Seeds for my appreciation of the arts as a vehicle to help us grieve were planted while I was working on a previous manuscript. I was preparing to travel from Pittsburgh to Iowa City to attend a writing workshop. My husband knew that I was working on a memoir that discussed the events surrounding the deaths of two of our three adult children. Saying goodbye to him, we hugged, and I headed down the stairs to get in the car that was taking me to the airport. From over my shoulder, I heard his message of casual concern, “I hope you find something more pleasant to write about.”

I knew my husband did not understand my turning towards memories of our family tragedies and writing about them. To him, this seemed a version of picking at one’s sores. I knew he wanted to protect me from what he saw as potential self-harm. In the preface to the manuscript that became Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and Rituals that Heal, I described how a powerful connection had formed between my art, my writing, and my grieving.

The writer’s workshop in Iowa City was held a couple of weeks after the town had suffered a significant flood. I brought home two empty sandbags, like the thousands of bags of sand stacked as barricades against the rising water. My empty sandbags had been decorated and made into handbags by artists in the community, then sold to raise money to help the local Habitat for Humanity fund the cleanup effort. Arriving home, I came into our bedroom and laid down my decorated sandbags alongside a folder of my writing. “My writings are my sandbags,” I told Rich. “We have to make art out of what happens to us, or at least something useful, and we don’t get to pick what that is.”

It was somewhat natural that I would turn to the arts to assist me in metabolizing my experiences of loss. Throughout a long life, for reasons that I often couldn’t explain, even to myself, I have continued to identify with my first profession as a dancer and practitioner of improvisation. Dancers know that words and reason, though often helpful, are not sufficient. We need art and the rituals it provides as containers and vehicles for the expression of our emotions and our stories. If done on our behalf, artistic expression—music, theater, poetry—provides access to the framework of our emotions and the distance we need to discover the meaning in our own experiences. When making art, drawing, painting, cooking, gardening, flower arranging, and decorating, we are taken into liminal space—that “space between the worlds”—where processing the losses of our lives can take place.

In 1993, according to the World Health Organization, approximately two million people were newly diagnosed with AIDS, raising the total since the start of the AIDS pandemic to more than fifteen million. In the US, most of them were gay men. My son was one of them.

In addition to the fact that there were little to no effective treatments for the disease, Ken had been advised by the AIDS Outreach Center that since he wanted to keep his job, he shouldn’t tell anyone, even his best friend, about his diagnosis. They had lawyers who would help him get his job back, but the better path was for him and his family to keep his diagnosis a secret. This was the big picture of what our family was dealing with when we came together in the spring of 1994 from Texas, Oregon, and Southern California in a hotel at the airport in San Francisco for an AIDS, Medicine, and Miracles Conference. There were two hundred professional caregivers, physicians, nurses, social workers, alternative medicine practitioners, and patients. Dazed and in and out of depression and denial, we were hoping for a miracle and were completely shocked to learn that, though the conference had been advertised for families, we were the only family members present.

There were helpful demonstrations and suggestions—acupuncture can alleviate the side effects created by Western medicines; meditation practice offers relief for the anxiety inherent in facing a life-threatening future. But it was the lunchtime presentation that stays with me to this day. There we were, in a large gathering space, seated at tables, opening our sandwiches from their plastic wrappings as the lights came up on a performance space elevated slightly above us. The session was not to be a lecture or demonstration but a presentation, a performance by the Wing It Performance Ensemble, directed by InterPlay founder and improvisational artist Phil Porter. I had recently been introduced to InterPlay through its other founder Cynthia Winton-Henry, a dancing minister, and, at that time, leader in the Sacred Dance Guild. I was amazed at our good fortune in being able to see the company perform.

The theme was AIDS and the group played with words we called out from the audience. They created dances, songs, and stories on the spot and in the moment around themes like fear, taboos, health, being gay, medicine, and, of course, miracles. Later, when I learned more about the InterPlay system, I realized there was a name for what was transpiring. The artists were dancing, singing, and storytelling on our behalf. They were doing one of the things the arts do best for mourners: affirming our experience and expressing for us what we need to have described in order to process the experiences of our lives.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.