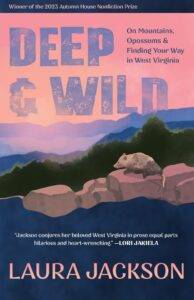

Pittsburgher Jacob Bacharach is the author of The Bend of the World and On the Doorposts of Your House and on Your Gates (on sale March 2017). We would like to formally thank Meredith Mileti (author of Aftertaste: A Novel in Five Courses) for lending us her copy of The Bend in the World because it is exactly what we’ve been wanting to read… if you haven’t already read it, we think you’ll love it, too.

“Jacob Bacharach has a great comic voice—shrewd, deadpan, and dirty—and The Bend of the World fears no weirdness. This should do Pittsburgh proud.” — Sam Lipsyte, author of The Ask

From the publisher: “In the most audacious literary debut to come out of the Steel City since The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, we meet Peter Morrison, twenty-nine and comfortably adrift in a state of not-quite-adulthood, less concerned about the general direction of his life than with his suspicion that all his closest relationships are the products of inertia. He and his girlfriend float along in the same general direction, while his parents are acting funny, though his rich, hypochondriac grandmother is still good for admission to the better parties. He spends his days clocking into Global Solutions (a firm whose purpose remains unnervingly ambiguous) and his weekends listening to the half-imagined rants of his childhood best friend, Johnny. An addict and conspiracy theorist, Johnny believes Pittsburgh is a ‘nexus of intense magical convergence’ and is playing host to a cabal of dubious politicians, evil corporate schemes, ancient occult rites, and otherwise inexplicable phenomena, such as the fact that people really do keep seeing UFOs hovering over the city…”

This, more or less, was how we ended up crushed in the back seat of Mark’s little fast car on our way to what Mark called Our Club. New friendships require less bargaining than old ones, less planning, fewer points to settle and details to iron out; for instance, I’d left my car on a side street in Oakland; if it had been Tom or Derek or even Johnny (not that the issue would have come up with Johnny, who didn’t have a car and did not, to the best of my knowledge, know how to drive), I’d have worried about that part—for no good reason, but nevertheless. But that evening it had seemed immaterial. The valets had brought Mark’s silver teardrop around, and we were off.

We whistled down Fifth Avenue, past the university and the hospitals, a pile of immense, mismatched buildings that climbed the hillside to our right like a stepped bastard ziggurat and from whose satanic bowels there emitted a constant Luciferian thrum. Packs of students crowded across the intersections. A helicopter passed overhead. We ran a red light.

Honey, Helen said, red means stop.

It was yellow.

It may have been yellow at one time.

Don’t worry. If I kill someone, we’re by the hospital.

Again, Helen said, a timing issue.

Beyond the hospital the road dropped in a steep S-curve toward the cantilevered highways that clung to the cliffs between the high bluff of the Hill District and the Monongahela. Across the river, lights stepped across the Flats and up the Slopes, and it struck me, not for the first, more like for the thousandth time, just what a preposterous place it was for a city, what a precarious topography. We crossed the Birmingham Bridge in a tight single lane between traffic cones. Whole lanes and great portions of the high arch and suspension cables were blocked and swathed in sheets of translucent plastic, which were illuminated from within by powerful work floodlights, revealing the silhouetted work of the tiny men within—tent caterpillars, ten million years hence, our successors.

We were on Carson Street briefly. A girl in tight pants vomited. Young men stood in gaggles outside of bars, simultaneously sinister and preposterous in their puffy jackets. I hate the South Side, I said.

Doesn’t Johnny live above Margaritaville? Lauren Sara had seemed to be sleeping before she spoke, her head canted back against the seat.

Yeah, I said. I keep telling him to get out of that shithole. We should stop and say hello.

Who’s Johnny? Mark asked.

My best friend.

Your only friend, said Lauren Sara, not cruelly, and anyway, I reflected, it was awfully close to being true.

We turned onto Eighteenth Street and wound our way up the Slopes. In the daylight, these were lovely neighborhoods, if a little run-down. The houses sat at odd angles to the streets, and the streets ran in switchbacks crosswise to the hills, and the whole thing was reminiscent of an Adriatic hill town, suggestive of a militarily defensible poverty, or else, not in the least because of all the little Slovak churches, of a winding stations of the cross, but there, at night, with the stands of houses suddenly replaced by bare sagging trees, with the occasional howl of a distant dog, with the old, orange streetlights buzzing and the intermittent creepy pickup truck rattling in the other direction with a slight few inches between sideview mirrors, with—was it me, or did everyone sense it?—something vague, insubstantial, and yet still threatening among the stands of weedy woods, something misty, something that, even if it didn’t have the material form to drag you down into a ravine and have its murky way with you, might just have the power to compel you to wander off on your own into the weeds, well, the point I’m making is that on a strange road in a strange car with people who were, after all, still strangers to us, there was something odd about that drive, something unsettling, something that strongly suggested no good would come of it.

But then, quite suddenly, we were above the city. We’d stopped climbing several minutes before and were winding through an unfamiliar neighborhood when we burst out onto Grandview. The city, at night, was like a strange ship, like a sharp barge splitting a larger river; the black tower of the Steel Building like a crow’s nest; the filaments of bridges like gangplanks, and you could almost imagine the whole thing plowing right on down the Ohio, hanging that gentle left onto the Mississippi at Cairo, and floating toward the Gulf; you could imagine waking one day to find yourself on an urban island, surrounded by water; or, anyway, I could imagine it, Atlantis, or thereabouts.

We ended up somewhere just off Grandview in a little commercial district with an Italian grocery, a storefront pharmacy advertising diabetic socks, and a few square cement-block buildings that might have been plumbers or repair shops. Mark parked along the curb across from the largest of them. Here were are, he said. There was light coming through the glass door. There was an unilluminated sign on the wall above it. the fraternal order of the owls, it read. nest #93. And underneath, painted right onto the blocks: A “PLACE” FOR “FAMILY.”

Excerpted from The Bend of the World by Jacob Bacharach. Published in August 2014 by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Copyright © 2014 by Jacob Bacharach. All rights reserved.