From the Publisher: “Julie’s first novel, The Tears of Yesteryear, was set against the backdrop of 1900s Pittsburgh, back when steel was king but life was anything but a royal dream for the millions of European immigrants who journeyed to America in search of a better life.

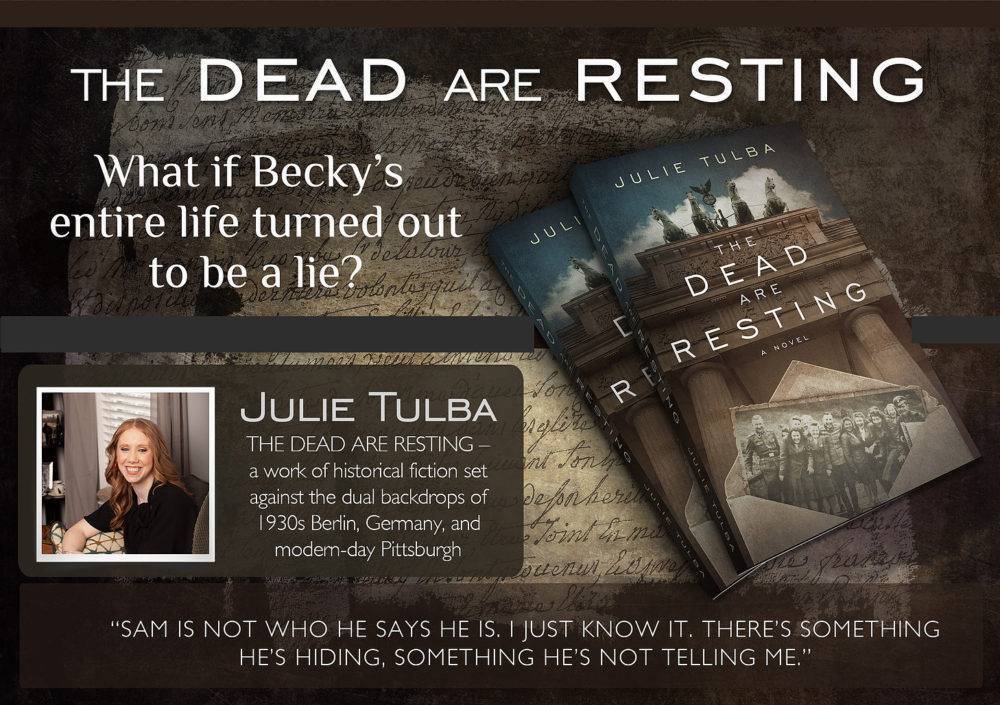

Her latest novel, The Dead Are Resting, once more set in Pittsburgh, is a family tale… of sorts. One in which you think you know everything there is to know about your family until the day comes when you discover that you actually don’t. That everything you once believed to be the truth, the crux of one’s identity, could all just come crashing down.Growing up in post-World War II America, Becky always knew who she was—the daughter of a Holocaust survivor—and yet a label that had never really defined her because of how her father was. The only survivor in his family, Becky’s father had always refused to talk about the past, having spent his entire adult life internalizing his pain and suffering rather than coming to terms with it. It’s because of this that her relationship with her father has always been one of tumult and discord. But what if her father was not really whom he said he was? What if he was someone else? What if Becky’s entire life turned out to be a lie?”

More info About the Author: Julie Tulba is a librarian and the author of two historical fiction novels, both of which are set in Pittsburgh. Her first book, The Tears of Yesteryear, an immigrant tale set against the backdrop of the Homestead Steel Works at the turn of the last century, was published in 2019 and this year saw the release of her second book, The Dead Are Resting, a dual-timeline novel set in modern-day Pittsburgh and Nazi-era Germany. She lives in the Pittsburgh area, passport always at the ready for her next international adventure (she’s traveled to 33 countries and counting), but also brainstorming ideas for her next novel.

Ecclesiasticus 38:23

PROLOGUE

Porąbka Village, Poland

July 1944

“So how do you like it here so far?”

“So how do you like it here so far?”The elbow to his ribs from Georg, his new friend of just a few short weeks, startled Max from his reverie.

“I’m sorry, what?” Max asked, glancing in the direction of the young woman who had asked the question but whose name he had already entirely forgotten. Inge? Ilse? Max was silently cursing himself for not being able to remember the name of a girl with such a pretty face. Of which he also noted, there was such a great abundance here at Solahütte.

“Dagmar here was just asking how you were liking it so far,” Georg told him.

“Dagmar,” he said to himself. Where on earth had I gotten Inge and Ilse from? he thought. Sitting up from his haunches he replied, “Oh, I’m enjoying it a great deal. I find the work challenging but fulfilling, although are there typically so many transports in a given week?” He posed this question to no one in particular since Georg, Oskar, and Johannes but also the girls, the ten Helferinnen, knew and were paramount to the camp’s operations.

“Not typically,” Johannes replied rather lackadaisically, having answered the question with his eyes closed, his hands behind his head, lying back on the picnic blanket as if he were having the most delicious slumber. “But,” he continued, “it was time we dealt with the issue of the Hungarian Judenschwein once and for all.” Johannes was the most senior officer of their small contingent even if he behaved like the most juvenile of schoolboys. Max had lost count of the number of times he had seen him pinching (and trying to pinch) the bottoms of the Helferinnen even if the girls had never seemed to mind, only ever playfully swatting away Johannes’ hand from their rears.

“Hey, no more talk of work,” one of the curly haired Helferinnen whom Max had christened Christa because she reminded him of his cousin Christa, an imp of a thing, demanded. “We’re supposed to be having fun,” and with that she grabbed Johannes’ cap, which had been resting on the ground next to him and took off, leaving him with no choice but to follow in close laughing pursuit, the sound of the river’s flowing waters able to be faintly heard in the distance.

Hours later, once their small group had fully exhausted themselves against the backdrop of the picturesque setting, signs of the late summer’s setting sun nearing, they were about to turn in when Johannnes called out, “Wait, let’s get a picture of everyone,” having noticed the Kodak Vigilant Junior six-20 camera that Max had had with him all afternoon.

The group congregated together on the little footbridge, Johannes smack in the center with all the Helferinne flocking him (naturally, Max thought), Georg on the right even posing with his accordion, having played countless tunes to their group throughout the day, when all of a sudden Johannes said, “Oskar, you take the photo and Max, you stand where Oskar was.” Max started to object, not feeling he had earned the right to be in this photo when he was such a newcomer, but Johannes ignored his protestations as did Oskar, who silently but gently took the camera out of Max’s hands and went to stand where only a moment before Max had been.

Max awkwardly joined the group, inching closer when Oskar called, “Max, get closer to Liesl, you’re not on focus,” not wanting to touch, still feeling a bit shy of girls even though he was nearly 23. But almost three years spent fighting on the barbaric wastelands of the Eastern Front and then recuperating in military hospitals from wounds he had sustained in battle, well, there hadn’t been a lot of opportunity for finding true love or even just heavy flirting.

“Okay,” Oskar cried out, “eins…zwei…drei…say cheese.”

The group in unison called out “cheese,” their smiles and gaiety visible on their faces, some of them laughing so hard they had tears forming in their eyes. They were so busy having such a wonderful time of themselves that none of them noticed the heavy bands of smoke that were rising above the tree lines just a short distance away.

Part I

Becky & Judy

CHAPTER 1

2006

Becky’s decision to go to Germany, the land of her father’s birth and childhood, was how their cold war began. Or as her father referred to Germany, “that place.”

“You go to that place you might as well be spitting on the memory of the six million who were murdered,” he told her the first time she mentioned she was interested in traveling to Germany. Or when she had told him she was just going to be visiting Munich and Berlin “this time,” he had said she was a “meshuggener” although unlike when her bubbe had called her that, her father was not calling her a crazy fool with any trace of affection. And when the time came where she affixed her itinerary to his refrigerator while he sat at the kitchen table watching her, he solemnly said with an air of resignation, “ka, was my own story, my own hellish experience not enough of a lesson for you? There’s so much of the world to see. Why do want to see the one place that tried and almost succeeded in completely destroying our people?”

She had no answer to that, as he knew she wouldn’t. So she just kissed the top of his head and left, calling over her shoulder with the words, “I’ll call you tomorrow.”

Her entire life she had been known as Becky but to her father she was and always would be Rivka, the Hebrew name for Rebecca. Growing up, her father liked to tell people that he had chosen the name Rivka because in Hebrew it means “a woman who takes a man’s heart” and that’s exactly what she had done the first time he saw her in the hospital.

It had bothered Becky a lot growing up, that her father wouldn’t call her by the American version of her name. It wasn’t enough that she already felt different being the only one in her class whose dad had that “tattoo” on his arm. But then he had to go and call her a name that sounded like it belonged to an old woman living in a 19th century shtetl, and not one living in 1960s Pittsburgh.

“Why can’t you just call me Becky like everyone else? I’m an American, I deserve to be called by my AMERICAN name,” she remembered yelling at her father one time during a fight in her adolescent years, saying this as if her constitutional rights were being infringed upon.

“Because that’s not your name. Your name is Rivka and you are the descendent of Abraham and Sarah, not Paul and Yoko,” he told her just as heatedly, not caring or realizing that one, they weren’t exactly “related” to Abraham and Sarah and two, Paul and Yoko weren’t a thing, at least not according to Dick Clark when she was able to sneak watching American Bandstand.

But Becky’s mom, Judy, got it. She’d understood her daughter’s wish to just want to fit in and not stand out, as she herself was the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants and knew all too well the callousness and sometimes cruelty of children when you had parents who were “different” and thus treated you differently.

Becky’s mom had grown up in a strict Orthodox Jewish household in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood in the 1930s, which she would tell Becky was like a shtetl as a means of making Becky feel better, letting her know that things really weren’t “so” bad with her father compared to how it had been during her own childhood. When she was a girl, her mother went to the mikvah each month following the end of her menstrual cycle, she couldn’t venture beyond the eruv even though she longed to go to the pictures or see a game at Forbes Field, and when she really wanted to make Becky smile, she would remind her about the weekly kishke that she was expected to eat. When Becky asked the first time what it was, since everything her bubbe made was delicious, Judy replied with a straight face and said, “beef intestine stuffed with a seasoned filling.” Thankfully even when bubbe had come to live with them, kishke never made an appearance. And Becky made a point to ask every…time…she saw a foreign looking dish on the dinner table.

Judy had contracted polio as a child and although she had recovered from it, her right foot was permanently disfigured, causing her to walk with a limp, thus rendering her “unmatachable” by the shadchan, the religious matchmaker. So her sisters Zipporah and Bina were married off to Jewish men (naturally from Suwalk, the same Lithuanian region their parents had come from), and her brother Moshe matched with a girl from Suwalk. Her mother Yehudit (or Judy as she preferred to be called, being a first generation American and the only one of the four siblings born in America), was left alone, which suited her just fine, knowing she would never need to shave her head and wear the sheitel, the wig that Orthodox Jewish married women had to wear in order to confirm with the requirements of Jewish law to cover their hair, or have to go to the mikvah each month to get clean so she could lie with her husband once more, or be told she couldn’t read a book that wasn’t the Torah. She had even convinced her parents to allow her to volunteer at the Irene Kauffman Settlement on Centre Avenue in the city’s Hill District. It was through her volunteer work there that she got to know and greatly admire Zena Saul and Anna Heldman, two women who worked tirelessly their entire careers on behalf of the city’s populations in need. And her volunteer work also served as the perfect cover when she made plans with her Gentile girlfriends to catch pictures at the Fulton, girls she had gotten to know outside of the eruv.

So when Judy ended up meeting and falling in love with a German Jewish refugee who had just arrived in Pittsburgh, a survivor of “the camps,” at one of the dances the Friendship Club held, no one batted an eye. They were just happy that Yehudit had found herself a nice Jewish man, even if he was German AND raised as a Reformed Jew AND didn’t speak a word of Yiddish. Someone had wanted to marry poor little Yehudit, lame leg and all.

This excerpt from The Dead Are Resting is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reproduced without permission.